The Humble Index Card

by Karen Fang

Today, the humble index card. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Can a small, blank piece of cheap card stock count as technology? Yes, it can, when size and shape are standardized, and the card belongs to a system of information organization.

The history of index cards begins even before the mass manufacture of paper and printing. In the 1700s, Swedish naturalist Carl Linneaus--now known as the "Father of Modern Taxonomy"--developed his theory of species categorization by dividing data onto identically sized pieces of paper. The practice--possibly inspired by playing cards--worked because each observation was broken down to its most basic fact, and new findings and categories could be added and reorganized by simply shuffling and inserting new paper.

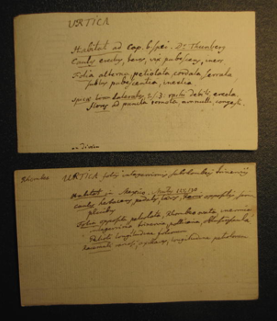

Two notecards prepared by Carl Linnaeus on different species of the Genus Urtica. Courtesy of Linnean Society, Library of the Linnean Society (London), and Creative Commons.

By the 1800s, index cards were combined with library card catalogs to aid police investigations. Early criminologists hoping to use physical appearance to identify suspects soon learned that height, weight, hair, eye color, nose shape, complexion, and scars were useless unless those facts could be quickly and effectively searched. But once divided on index cards and sorted like library card catalogs, police pioneered the first usable form of biometric surveillance.

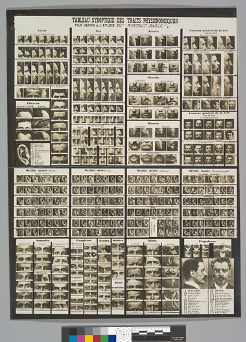

Nineteenth-century French police cards for classifying physical attributes. Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art and Creative Commons.

Today we think of surveillance as a digital and photographic phenomenon, performed by machines, but actually the practice precedes the computer, and was first possible because of index cards. And while surveillance is controversial, we rarely recognize its precedents in early technologies like the index card, or how a simple, seemingly innocent thing like a blank piece of paper can wield such analytic power.

If by now you're feeling a little creeped out by index cards, let me temper that by also pointing out their capacity as a vehicle for creativity. Many authors use index cards to compose. Vladimir Nabokov always plotted his novels by first drafting the story on index cards. In his 1962 novel, Pale Fire, Nabokov portrays this practice through a self-referential plot about the index cards on which a poet's final, unpublished work is inscribed.

For more modest authors like myself, I like to think about how index cards shaped greeting cards, and how pre-printed, mass-manufactured cards can facilitate human connection. J.C. Hall, the founder of Hallmark Greeting Cards, always kept index cards on hand so he could jot down ideas for new cards. If a sentiment couldn't be written on a 3x5" piece of paper, Hall reasoned, it was too wordy to be effective.

Back of Hallmark greeting card. Creative Commons.

The index card is the ultimate tabula rasa, a blank slate on which much can be recorded and processed. It's the forerunner of some of our most powerful machines, but it's also a space for imagination and human connection. You probably know Hallmark Greeting Cards' motto: "When you care enough to send the very best." That was first written on an index card, a simple but potent technology that can be both a powerful tool of analysis and an important vehicle of human feeling.

I'm Karen Fang, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Daniela Blei, "How the Index Card Cataloged the World." The Atlantic, December 1, 2017.

John Lienhard, "End of a Card File." The Engines of Our Ingenuity, Episode #440.

Colin Marshall, "The Notecards on Which Vladimir Nabokov Wrote Lolita: A Look Inside the Author's Creative Process." Open Culture, February 5, 2014.

Jonathan Schifman, "How the Humble Index Card Foresaw the Internet." Popular Mechanics. February 11, 2016.

Patrick Regan, Hallmark: A Century of Caring. Kansas City: Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2009.

This episode was first aired on June 30, 2020