Exploration by Presence and Proxy

Today, exploring by presence and proxy. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

We in the spaceflight community are often confronted with the debate on whether space exploration is best done by humans or autonomous probes. At the center of the debate are risk and cost effectiveness, vetted against return of scientific knowledge. But it's a silly argument really, one that artificially pits human against machine in a contest of exploration worthiness.

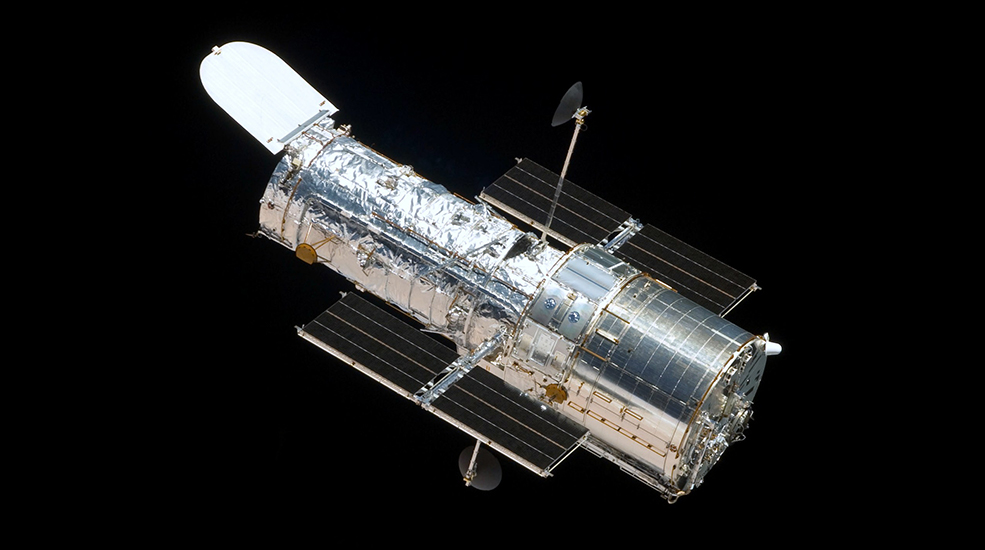

The venerable and ground breaking Hubble Space Telescope, launched in 1990, has been returning astronomical data and imagery that can be only be described as transformative for three decades. This picture was snapped from the Space Shuttle Atlantis during the fourth and final servicing mission in May of 2009. By coincidence I was on the International Space Station at the time working on science investigations. The juxtaposition of human-serviced spacecraft and simultaneous human-crewed research platforms highlights our parallel efforts in space exploration.

Photo Credit: NASA.

A region of the Carina nebula in the constellation of the same name imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope. Unceremoniously dubbed Herbig-Haro 901 and 902, the pillars here are a few light years across, each light year being nearly six trillion miles, and contain massive high velocity jets of ionized gas and harsh radiation involved in formation of new stars. Hubble imagery offers a beautiful visual reference that all can relate to.

Photo Credit: NASA.

Humans and remote probes are natural and longtime partners in space flight. Satellites preceded humans into Earth orbit - and measured radiation, thermal conditions and other key aspects of the space environment. Before the Apollo 11 crew landed in the Sea of Tranquility, a brisk program of lunar orbiters and landers from the US and Soviet Union had mapped much of the lunar surface and performed soil analysis. This information was critical in selection of landing sites and anticipating what human crews would encounter, and greatly reduced the risk for the first visits.

Even during the 60's, both the US and Soviet Union sent probes out of Earth vicinity to the inner planets. These early missions were rife with failures as rocket technology and instrumentation developed, but the information returned began to transform our understanding of these worlds. In the following decades, Magellan, Galileo, Cassini, New Horizons and other celebrated probes provided knowledge and stunning imagery of the outer planets. And nearly everyone carries a stark image of the Martian surface thanks to the fleet of satellites and rovers we have sent there. The two Voyagers spacecraft, launched in 1977, have passed the borders of the solar system, giving us a lofty sense of having expanded our presence into interstellar space.

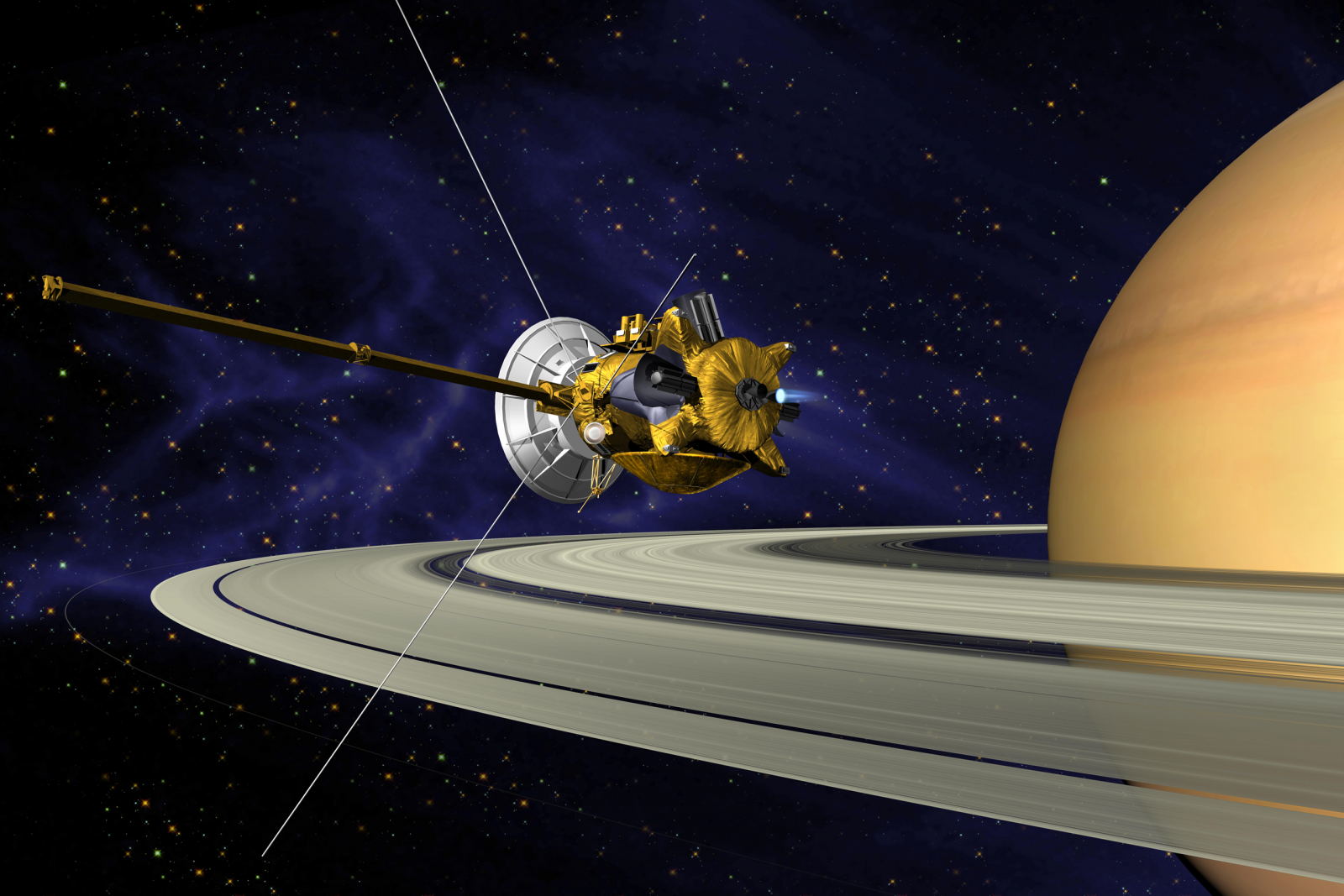

One of our flagship scientific projects, the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft is seen here arriving in orbit of Saturn in late 2002, about 5 years and several gravity assist flybys of Venus, Earth and Jupiter after launch. Along with collecting amazing data and spectacular imagery of Saturn, its rings and moons, the spacecraft deployed the Huygens probe to land on the surface of Titan, one of the major moons. (This of course is an artist's rendition; sadly we did not have an interplanetary "chase plane".)

Photo Credit: NASA.

Of course the fundamental missions of remote probes and humans are vastly different. The probe is a scout crafted to collect and return science data. The human mission that may follow is about exploration, expansion, cooperation, commerce, inspiration, and of course science. And humans are still unique as explorers. As for our sophisticated probes and rovers, each individual carries with it a suite of exquisite sensors. But the 5 basic human senses are force multiplied in real time by the mental processing of the observer, able to synthesize inputs into a holistic picture and immediately follow an unplanned path. A remote probe will discover big things it was designed to look for. But it may be easy to elude a purpose driven probe, if you are not its purpose. A human is not so constrained and will look for everything.

Debate aside, the history of any great civilization will not be marked by the number of peer reviewed articles in high impact journals, nor in the spectacular imagery that we relish from our mechanized scouts. The history, and I would argue the worthiness of a civilization, will be much more tied to what they did with that knowledge, how they were inspired by that imagery, and how it affected their understanding of their world - or the worlds they were expanding into. No matter where you fall on the relative value of human vs robotic exploration, here is how I prefer the human race not be eulogized: "They ended, enlightened by their marvelous machines of distant and wonderful worlds, having never left their own....."

The primary mirror arrangement of the James Webb Space Telescope, set to launch in 2021. Eighteen hexagonal mirror segments combine to form a massive "light bucket" with five times the area of Hubble. Due to its heat sensitivity, the JWST will reside away from Earth vicinity, which will all but preclude visiting astronauts for repair and maintenance. Incredibly complex but highly capable, the JWST should be a most worthy successor to the Hubble.

Photo Credit: NASA.

I'm NASA astronaut Michael Barratt, and like the University of Houston, we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

It is remarkable how often we get this question when speaking about human space flight: basically why send humans with the expense and risk when we can send robots? It seems a bit one-sided, since there is never a robot in the audience advocating for human space flight. But this can be quickly seen as humans on both sides assessing trades and weighing the pros and cons of two major arms of space exploration. As one privileged to travel in space, I can tell you that astronauts are not threatened by robots and probes, and they are certainly not threatened by us. Neither do they reflect the awe we feel when they are delivered on target and reveal secrets. No one is more jazzed by the breathtaking imagery of the Martian surface returned by the Curiosity rover or the star forming nebulae seen by the Hubble Space Telescope than the human spaceflight community.

Obviously we can currently send our semi-autonomous probes much further than we can a human crew. But the findings entice us outward. It is no stretch to say that probes like Magellan, Cassini, and New Horizons along with the amazing teams behind them count among our heroes. Remove the perceived budgetary rivalry and you will find an intense tie in long term intent and purpose. And I use the word ‘perceived’ here because it is doubtful that curtailing human flight programs would automatically transfer to remote science programs, or vice versa. Because there are different motivators with different outcomes, it is simply not a zero sum game.

It is worth emphasizing that the generic term 'robots' when applied to space exploration has many different embodiments. Vastly simplified here, these include:

- Remote deep space probes, such as the Voyagers and New Horizons, that travel past interesting destinations and continue outward. Way outward.

- Remote deep space planetary orbiters, such as the Magellan mission to Venus, Galileo mission to Jupiter, and the Cassini mission to Saturn.

- Surface rovers, such as the storied Spirit and Opportunity rovers and now the Curiosity rover on Mars; and of course several have visited our closer neighbor the moon.

- Surface landers, such as the Vikings to Mars and the Russian Venera missions to Venus.

- Space telescopes, which may be in Earth orbit, such as the Hubble and Chandra X-Ray Observatory, or more remotely placed telescopes such as the Spitzer infrared telescope or the Kepler space telescope, both of which orbit the sun. The James Webb Space Telescope will be placed in an Earth-sun Lagrangian point over 900,000 miles beyond Earth orbit to escape effects of Earth's radiated heat. An ultra-cool mirror will allow infra-red observations beyond what has been possible, looking at the most distant objects in the universe as well as direct imaging of extra-solar planets.

Then there are the smaller scale units that travel with and more closely assist human explorers and space workers. These are heavily fantasized in science fiction, in the form of personified 'droids' in the Star Wars franchise and more sinister artificial intelligence carrying robots in may sci fi yarns. We do expect eventual help from such systems both in orbiting platforms and lunar and Martian surface activities. The well-known and press-friendly Robonaut, which we delivered to the International Space Station on my Shuttle mission (STS-133 in 2011), is one early example, and more recently the Russia robot Feodor spent several days onboard the ISS. Both are early prototypes, but there is no question that this effort has momentum and offers promise.

For those that wish to read more, here are some articles by various illuminati on the discussion.

Jared Keller: Why Space Exploration Is a Job for Humans Click here.

Don Lincoln: Machines, not people, should be exploring the stars for now. Click here.

Francis Slakey and Paul Spudis: Robots vs. Humans: Who Should Explore Space? Click here.

Joshua Colwell: Robots vs Astronauts Click here.

This episode was first aired on March 24, 2020