Sputnik Educates America

Today, a satellite shocks American education. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In the fall of 1969, I began my sophomore year as physics major at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey. In the first class of Psychology I, our instructor asked why we had chosen to study engineering and science. He was new to the college, and had never taught a group of technology students before.

I am pretty sure that he was expecting to hear that we were greatly interested in the subjects, or that we saw technology as a path to rewarding careers, or maybe that we were following a family tradition or family mandate.

When no one answered, I raised my hand. "We're here because of Sputnik," I said. "Sputnik went up, and we were told that he had to become scientists and engineers." Many of my classmates agreed. We were all born in 1950, and from age seven or so, we were guided into technical fields. All thanks to Sputnik.

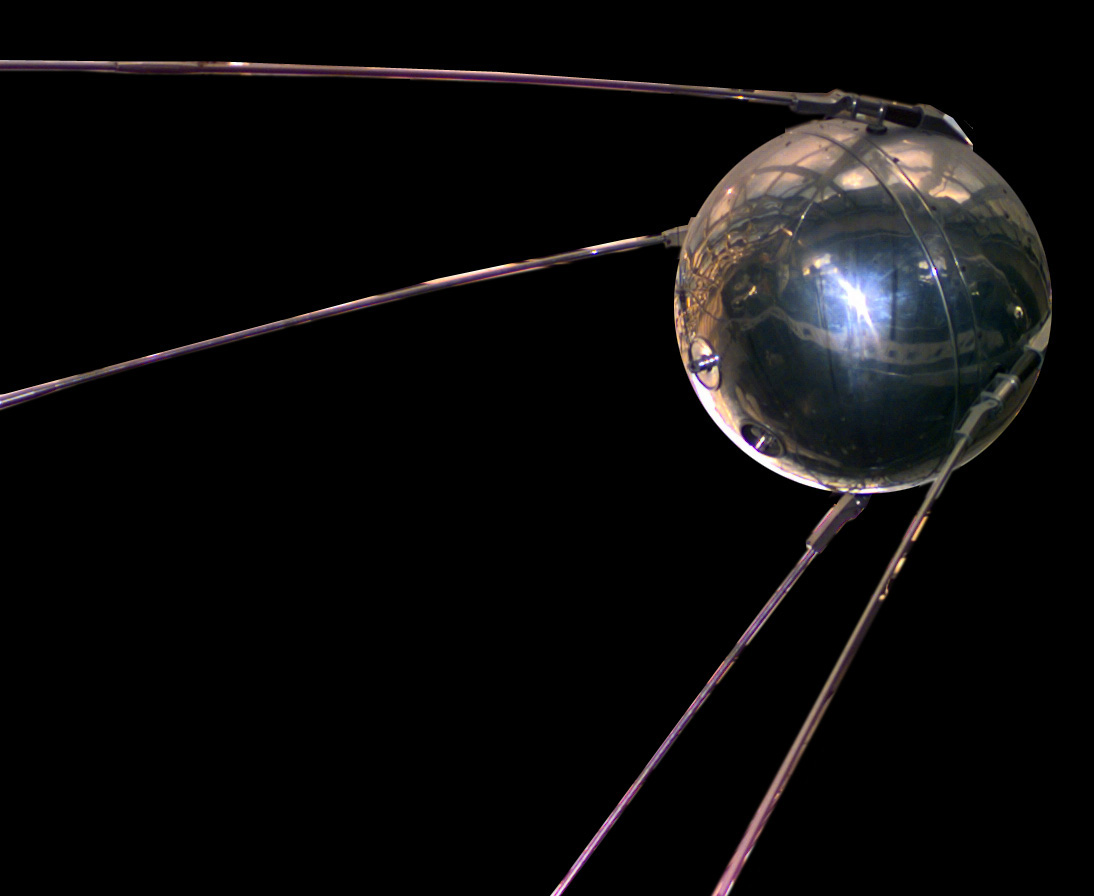

Sputnik

Photo Credit: Wikipedia.

Sputnik was the first man-made satellite, a metal sphere about two feet in diameter, launched by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957. It orbited the Earth for a few months, beeping every 0.7 seconds until its batteries died, and then fell into the ocean.

The "Russians" had definitely taken a lead in the Cold War. The terror triggered in America might be hard to grasp today. I can't say that at age seven I grasped all that was going on, but I certainly knew about the concerns over Sputnik. Everyone my age did, and we were expected to do our part.

The populations of the Soviet Union and the United States were roughly the same size, but American colleges turned out less than half as many graduates in technical fields. That had to change.

The changes probably affected our teachers more than we students. My grammar school teachers were mostly elderly women. They aimed to train us to move into our fathers' and mothers' lives. Sputnik launched, and our teachers were now to launch us onto careers that some of our parents could hardly conceive.

Some teachers had a hard time with the transition, but they rose to the challenge. Science and math classes were pepped up, sometimes spiced with visits from local companies working in technical fields. No visits from lawyers or medical doctors. None from bankers or businessmen, but many from engineers.

Science projects, science fairs, science clubs became commonplace. Another regular event was the launching of America's Mercury astronauts into orbit. Our teachers would wheel a television set into class and tune to the rocket take offs. We did not see many launchings. We watched the constant starts and stops in the countdowns, and the postponements and delays. Those turned into long days indeed.

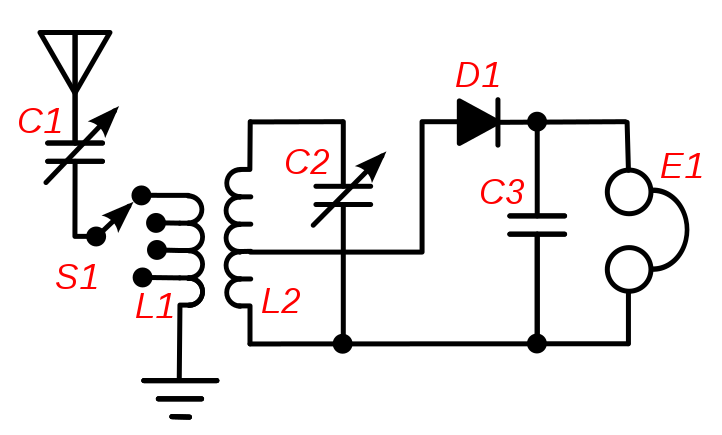

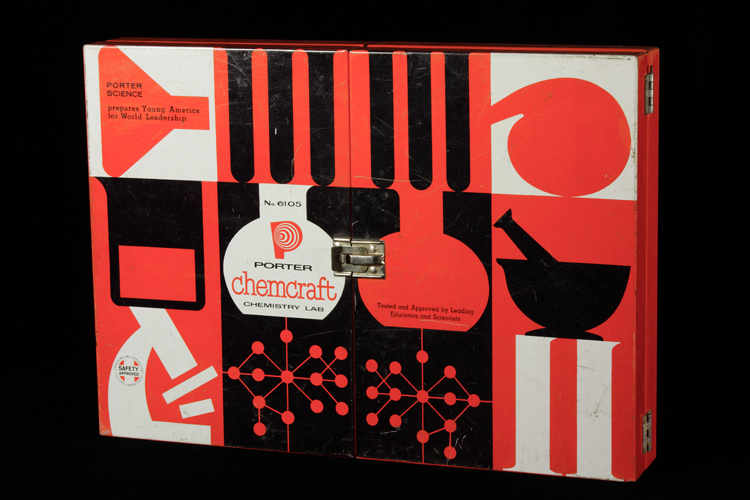

Live television may have let us down, but the new direction of our early education succeeded in making many of my generation enthusiastic about science. For Christmas and birthdays, kids like me got chemistry sets, microscopes, telescopes, and what now would be seen as comically primitive computers—no electronics, all wires and dials.

Crystal radio circuit

Photo Credit: Wikipedia.

Porter Chemcraft Senior Set

Photo Credit: Porter Chemcraft.

Most of the top students in my high school classes went to science and engineering colleges. Thanks to Sputnik -- a metal sphere that did nothing more than beep -- America had its new generation of engineers and scientists.

I'm Frank Dello Stritto, for the University of Houston, and interested in the way inventive minds work.

"Sputnik Crisis" on Wikipedia.

Dickson, Paul. 2001. Sputnik - The Shock of the Century. Walker & Company. New York

Halberstam, David. 1993. The Fifties. Random House. New York.

This episode was first aired on March 17, 2020