Sharing Computers

by Andy Boyd

Today, thinking big - really big. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Imagine you had at your disposal the most powerful computer in the world. What would you do with it? It's not entirely a hypothetical question.

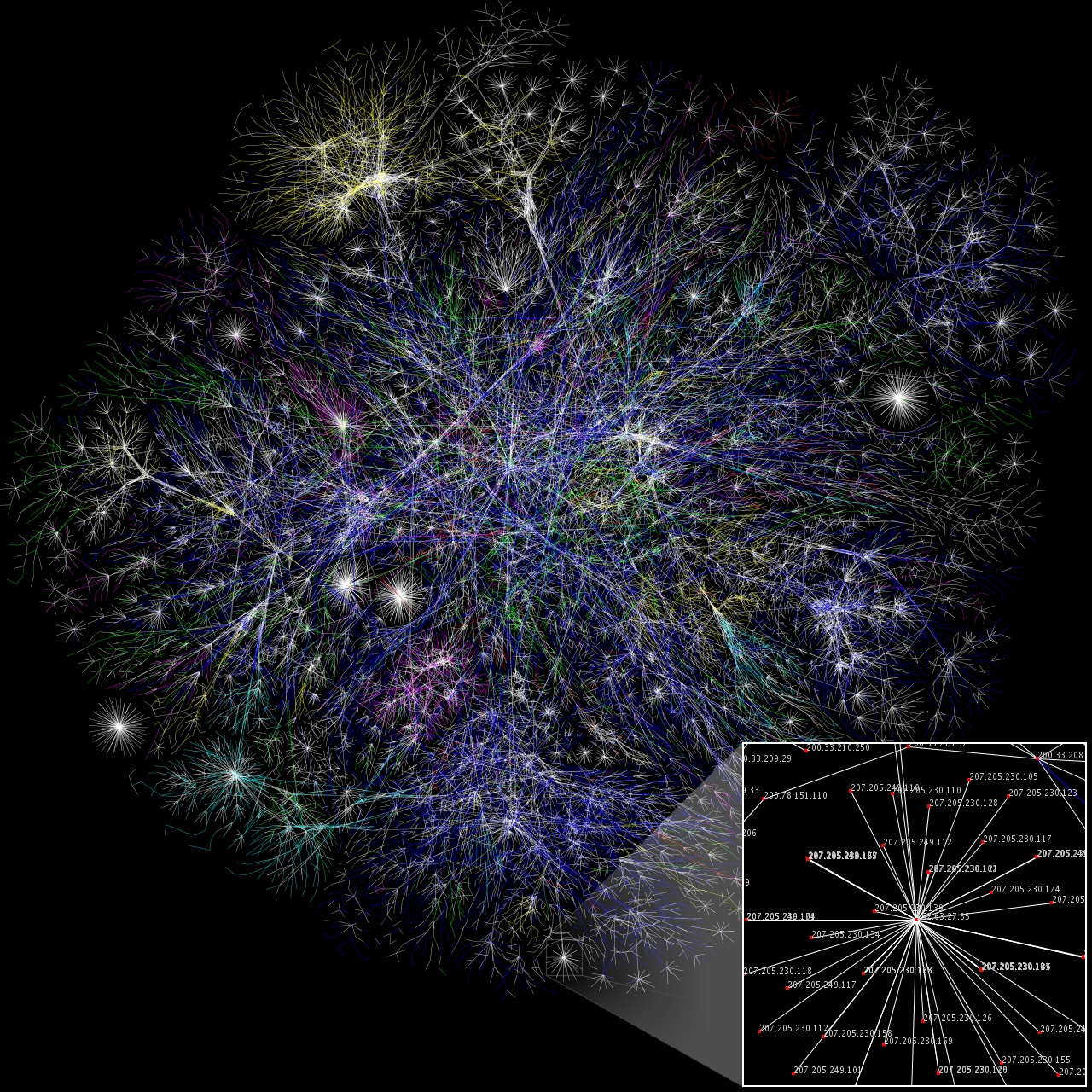

Internet map

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

In 1996 George Woltman had an idea. He wanted to look for numbers called Mersenne primes, named after a seventeenth century French priest. Start with any number that's one less than a power of two, say, 7 - which is two to the third power minus one. If that number is only divisible by itself and one, as is the case with 7, it's a Mersenne prime. It turns out it's relatively simple to make that divisibility check for even very large powers of two. Easy, that is, if you have a computer. So Woltman created software that allowed him to use the internet to enlist the aid of fellow enthusiasts. When a personal computing device wasn't busy, Woltman's software took over and started looking for Mersenne primes. In March of 2018, over 1.7 million computers were engaged in the project.

Woltman's effort is often held up as the germinal project of its kind. Since its inception, many such computing projects have taken off. One of the most famous, SETI@home, was established in 1999. The project employs over five million computers in the ongoing search for radio signals from extraterrestrial intelligence.

Very Large Array

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Not surprisingly, distributed computing projects tend to be heavily focused on science and math. Some projects have neither practical nor theoretical value. Finding ever larger Mersenne primes achieves essentially nothing. It's more sport than science. But many more projects attempt to answer important scientific questions. The project Einstein@home searches for pulsars and gravitational waves. It puts some 2.7 million computers to work. Folding@home examines how the strands of molecules in proteins fold together, something that's important in understanding diseases like Alzheimer's. More than 8.3 million computers are busily calculating away.

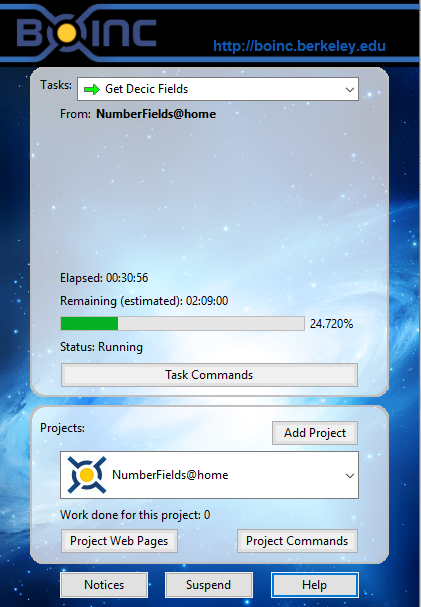

If you have a good idea that needs a little computational help, and you have some computer savvy, you can set up your own distributed computing project. One of the more popular software programs for doing this is BOINC - the Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing. Of course, you'll have to convince people to agree to share their computers. It's a lot easier to join an ongoing project. Simply download an app, pick the project you're interested in, and you're done. Just be sure to leave your computer on. Personal computers. Smart phones. Even some video game consoles can be used.

Of course, participating comes at a cost. The constant calculating uses energy that you are paying for. But if you're involved in a project you care about, consider it a donation. And don't forget the excitement! Imagine if your computer found the first sign of extraterrestrial intelligence. And the glory! You could find your name attached to a new celestial body. You just need to think big - really big.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

For simplicity, the essay refers to the number of computers working on various projects. More precisely, the numbers represent the number of processing units or cores.

The number of computers working on any given project is fluid. The numbers presented here were taken from the Wikipedia website Click here on November 27, 2018.

BOINC. From the University of California, Berkeley website: Click here. Accessed November 27, 2018.

The Einstein@home website: Click here. Accessed November 27, 2018.

The Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search website: Click here. Accessed November 27, 2018.

SETI@home. From the University of California, Berkeley website: Click here. Accessed November 27, 2018.

SETI@home. From the Wikipedia website: Click here. Accessed November 27, 2018.