Friedrich Fröbel and Kindergarten

by Andy Boyd

Today, we play. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

How do we learn in school? At some point, it's lectures, books, and tests. But not when we start; not in kindergarten.

Kindergarten's roots are found in the work of Friedrich Fröbel in the early days of the Enlightenment. Fröbel lived at a time when educational principles were being carefully rethought throughout Europe. Catholics and Protestants of the day may have been worlds apart on doctrine, but they were of a similar mindset when it came to education. Children were inherently sinners - a consequence of original sin - and they needed rigid structure and stern guidance to grow properly. But that perspective began to change. Perhaps children were inherently good. If so, what could educators do to nurture this goodness?

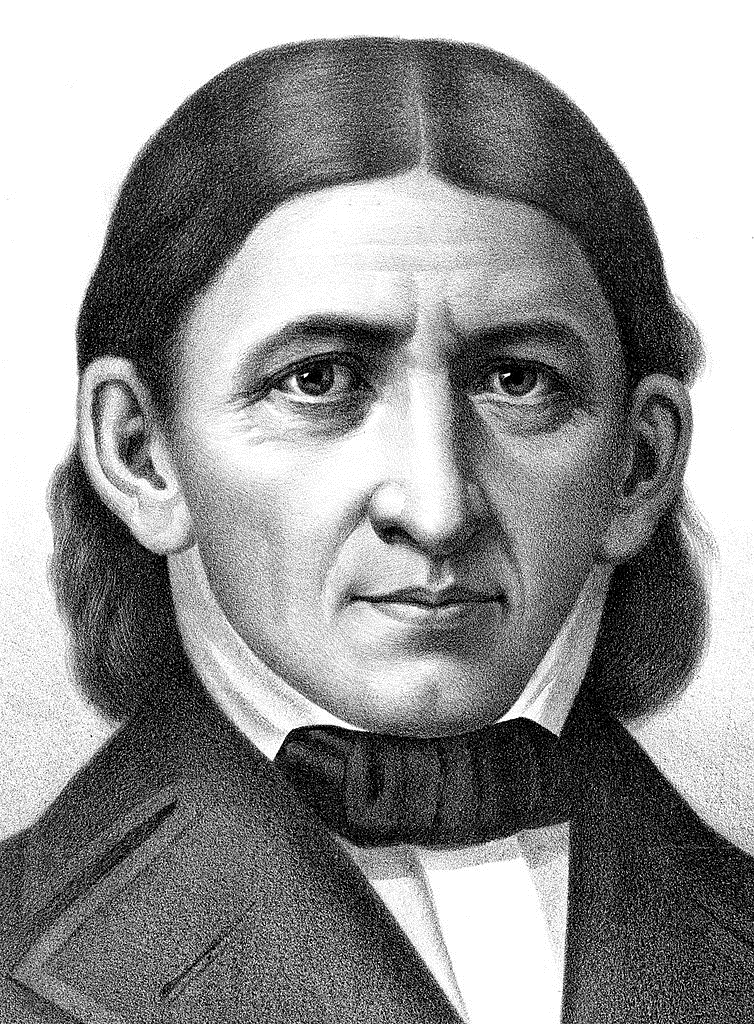

Frederick Fröbel Bardeen Photo Credit: Wikimedia

Central to Fröbel's educational philosophy was unstructured activity. Singing. Dancing. "The plays of childhood," he wrote, "are the germinal leaves of all later life." Plants were more than just a metaphor for Fröbel. He believed children knew how to grow innately, like flowers springing from the ground. The proper way to educate a young child was simply to keep the soil moist and fertile, then let nature take its course. The word kindergarten, coined by Fröbel, is composed of the German words for child and garden; it's a place where children can grow.

Fröbel placed emphasis not only on play, but on toys. Fröbelgaben -- translated as Fröbel's gifts -- were a sequence of toys carefully designed to nourish the growing mind. The first gift consists of soft balls attached to strings; the second, a wooden sphere, cube and cylinder. These are followed by ever more elaborate collections of three dimensional blocks, two dimensional tiles, and one dimensional sticks. Lego, Tinkertoys, Lite-Brite, and the wealth of creative toys our children play with today are descendants of Fröbel's gifts.

Some of Fröbel's gifts, taken from the Fröbel Gifts website: http://www.froebelgifts.com/index.htm Photo Credit: FröbelGifts.com

The son of a Lutheran minister, Fröbel was devoutly religious, and it poured over into his educational philosophy. Education that didn't have religion at its foundation was, in Fröbel's words, "fruitless." Original sin may have been cast out, but God clearly wasn't. To Fröbel, play was the "free expression of what is in a child's soul," giving "joy, freedom, contentment, inner and outer rest, [and] peace with the world."

Fröbel also recognized, and encouraged, women in their role as first educators. "The destiny of nations lies far more in the hands of women -- the mothers -- than in the possessors of power," he once said. "We must cultivate women, who are the educators of the human race, else the new generation cannot accomplish its task." Not surprisingly, Fröbel had a steadfast following of women who embraced and perpetuated his ideas. It wasn't just okay to be a mother. The very "destiny of nations" was in their hands! A destiny that blossomed from the care and nurturing they provided in their kindergartens.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Norman Brosterman. Inventing Kindergarten. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002.

Sarah Fishman. The Battle for Children: World War II, Youth Crime, and Juvenile Justice in Twentieth Century France. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Fröbel's Kindergarten. http://www.froebelweb.org/web2004.html. Accessed October 15, 2018.

Man is a Creative Being! Words of Friedrich Fröbel. http://www.froebelweb.org/web7001.html. Accessed October 15, 2018.