Mary Golda Rises

by Andy Boyd

Today, reaching for the sky. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Skunkworks. It's a common term for a nimble, independent group on a mission to do something important - a kind of industrial special-ops unit. But the term traces its roots to a specific group that the aerospace contractor Lockheed formed during World War II. Actually, the roots go even deeper, to the name of a moonshine distillery in the then-popular comic strip L'il Abner. Lockheed Martin still holds the trademark on the term "Skunk Works" when spelled as two capitalized words.

Skunk Works logo Photo Credit: Wikimedia

Those asked to participate in Lockheed's secretive Skunk Works were always exceptionally talented. And among the forty founding participants was one Mary Golda Ross.

Ross was born in 1908 in the foothills of the Ozark Mountains. Of Cherokee decent, she was sent to live with her grandparents in the Cherokee Nation capital of Tahlequah, Oklahoma. There she was able to develop her skills in mathematics - her favorite subject - graduating from a state teachers college at the age of twenty. For nine years she taught science and math locally, but grew restless - happy with what she'd achieved, but wondering if she could achieve even more. So she took a statistical desk job in Washington at the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. When a Cherokee woman from the Department of Education recognized her skills, Ross was sent into the field as the girls' advisor at what would become the Institute of American Indian Arts. In the summers, she worked on, and earned, a master's degree in math.

Cherokee National Capitol Building Photo Credit: Wikimedia

When the U.S. entered World War II, Ross moved to Los Angeles on the advice of her father where she was hired by Lockheed to perform mathematical calculations. But as she worked side-by-side with engineers versed in the details of aeronautics, she proved just how capable she was. With a persistence that kept her working late into the evening, her managers were impressed. When the war came to an end, many women who were hired to support the war effort were sent home. But not Ross. Instead, Lockheed sent her to UCLA for professional certification in engineering. Unlike her prior training in teaching general math, Ross studied the equations of aeronautics and celestial mechanics. And when she returned to Lockheed, she was perfectly positioned to support the U.S. efforts to win the space race with the Soviet Union. Satellites. Space flight. Interplanetary space travel. These were the activities in which Mary Golda Ross blissfully immersed herself.

Gemini and Agena D Photo Credit: Wikimedia

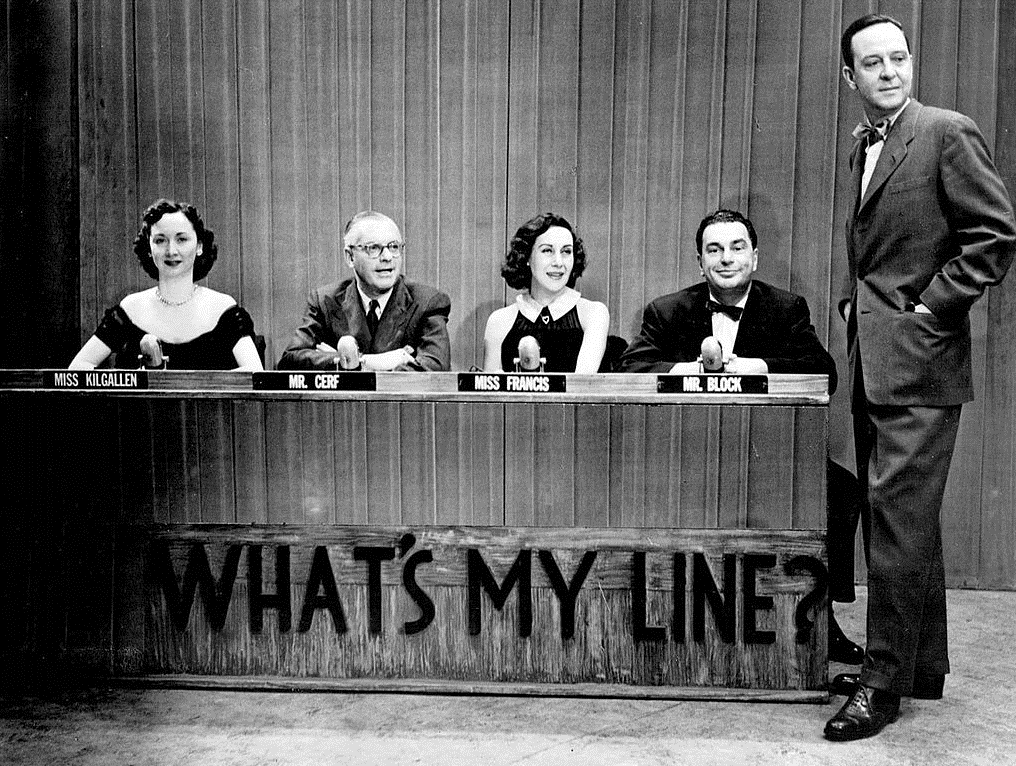

Ross lived a fulfilling life, working in retirement to attract women and Native American youth into engineering careers. She died in 2008, just months shy of reaching the age of one-hundred. Along the way she even appeared on the popular television game show What's My Line, where a panel of celebrities asked questions to determine a contestant's line of work. Imagine what an impact Ross's career must have made on audiences of the late nineteen-fifties.

What's My Line original television panel 1952 Photo Credit: Wikimedia

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Many thanks to listener Robert Wells for bringing the life of Mary Golda Ross to my attention.

Cherokee Rocket Scientist Leaves Heavenly Gift. From the Cherokee Phoenix website: https://www.cherokeephoenix.org/Article/Index/2470. Accessed August 15, 2018.

Meg Godlewski. "How Skunk Works Got Its Name." General Aviation News, November 4, 2005. https://generalaviationnews.com/2005/11/04/how-skunk-works-got-its-name. Accessed August 15, 2018.

Mary G. Ross. From the Wikipedia website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_G._Ross. Accessed August 15, 2018.