Water System Rehabilitation

by Andy Boyd

Today, we rehabilitate. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

At times of quiet reflection I often find my mind drifting to thoughts of just how fortunate we are. And it needn't drift to anything very complicated. Access to a hot shower with a simple turn of a knob is an undeniable pleasure on a cold winter day. If you're like me, that shower may even be the source of quiet reflection. Such a simple pleasure I'll think to myself. Then my inner engineer awakens and I realize it's not a simple pleasure at all.

Shower Head Photo Credit: Flickr

In the U.S., over ninety-nine and a half percent of us live in homes with fully functioning plumbing systems: that's over three hundred twenty five million people with one plumbing system delivering clean water into their homes and another carrying wastewater away. Estimates from a 2013 report by the EPA put the number of main pipelines in the U.S. stretching over a million miles, possibly twice that. To that we can add almost another million miles of service lines connecting individual homes into the system. And all of these pipes are aging.

The longevity of a pipe depends on factors ranging from where it's located to what it's made of, but most are designed to last about fifty to one hundred years. That means many pipes, especially in older cities, are in need of repair, replacement, or, as is now increasingly popular, rehabilitation.

Imagine a pipe with enough leaks and cracks it really needs replacing. Replacement's a messy proposition as streets are torn up and pipes buried. Why go through all that work, thought engineers, when the old pipes already form perfectly good underground passageways? One form of rehabilitation involves simply running a new pipe through the middle of an old one. It's simple and frequently an adequate solution, but it reduces the pipe's diameter and therefore the amount it can carry.

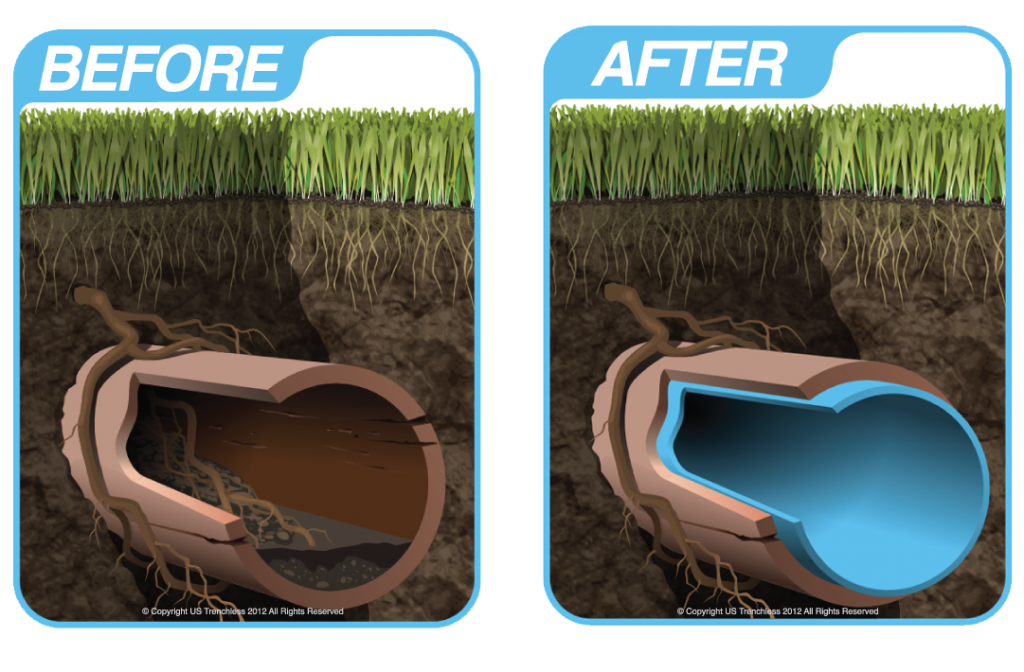

So to get the most from rehabilitation, engineers have developed a variety of coatings and linings to cover the interior surfaces of old pipes. These coatings and linings provide strength and a cleaner, smoother surface, while minimally affecting the pipe's diameter. And some of the methods are just plain ingenious, on par with the creativity applied by the medical profession in its efforts to fix clogged circulatory systems without major surgery.

Cured-In-Place-Pipeline Before After

Cured-In-Place-Pipeline demonstration Photo Credit: YouTube

And that's a fitting comparison. Just as blood carries life to the cells in our bodies, our pipeline infrastructure provides its own kind of life to the people in our great cities. I pondered our achievement as I let the warm water stream down my hair and over the back of my neck. Then it hit me, with a jolt that caused my inner engineer to awaken once again. There was yet another great achievement allowing me to enjoy my shower: the heat that made the water warm. But that's the story of yet another pipeline system that we'd probably best save for another day.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Thanks to colleague David Wood for bringing the topic of this essay to my attention.

Christopher Ingraham. "1.6 Million Americans Don't Have Water. Here's Where They Live." The Washington Post, April 23, 2014. See also: https://www.washingtonpost.com. Accessed October 31, 2017.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. State of Technology for Rehabilitation of Water Distribution Systems. March, 2013. See also: https://nepis.epa.gov. Accessed October 31, 2017.