Philosophical Zombies

by Andy Boyd

Today, zombies. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

When you think of zombies you probably think of decomposing corpses brought back from the dead; mindless, soulless bodies who, for some reason, want nothing more than to consume the living and thus perpetuate zombies. They're certainly popular in horror films, but zombies are also a central fixture in a respectable academic discipline: philosophy. You can discover just how widespread they've grown by googling "philosophical zombie."

Photo Credit: Wikimedia

Philosophical zombies aren't the blood-thirsty creatures found on movie screens. In fact, if you were to meet one on the street you wouldn't be able to tell him apart from your next-door neighbor. He'd laugh at your jokes, share stories about his kids, enter into a lively discussion about politics, and complain about work. What philosophical zombies do share with their horror film counterparts is mindlessness. They may look and act like humans, but there's nothing going on inside. A philosophical zombie may laugh, but there's no inner sense of "funny." He may smile broadly and tell you his daughter got an A in algebra, but there's no inner sense of pride or happiness. For such as him, there's no inner sense of anything.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia

Philosophical zombies are of interest because they touch upon one of the central questions in artificial intelligence. The now famous Turing test asks if a machine can interact with us in such a way that we can't tell if it's a machine or a human. But even if a machine were to convince us it was human, thus passing the Turing test, there's no guarantee it's feeling anything inside. If not, it's a philosophical zombie. And philosophers are left to ask if such beings could exist. Can we separate acting like a human from experiencing at least some of what it's like to be a human?

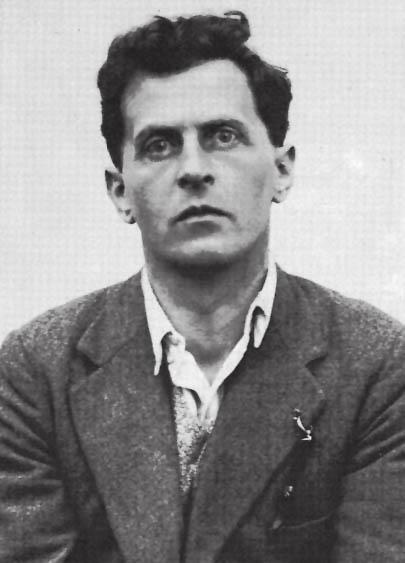

Ludwig Wittgenstein. Photo Credit: Wikimedia

Philosophers go even further. Imagine a world identical to our own, inhabited not by machines but by biological entities just like humans down to the last molecule. There's only one difference. The people who live on this world are zombies. Not a single person has inner feelings. If you poke someone with a pin, they'll react with a painful expression and tell you it hurts, but they aren't feeling pain. Is it conceivable, ask philosophers, that we can imagine such a world? And if so, why do we here on planet earth experience the pain from a pin prick? I for one feel it, and I presume you do, too.

Philosophy is a wonderful discipline because at its very best it addresses life's bigger questions with a creative use of logic. In that way, it's a lot like math. Still, when it comes to zombies, I suspect most of us would just as soon set philosophy aside and content ourselves with watching Dawn of the Dead. Or maybe Shaun of the Dead. Or Return of the Living Dead. Or World War Z. Or Zombieland. Or Land of the Dead. Or...

Zombies as portrayed in the movie Night of the Living Dead. Photo Credit: Wikimedia

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Zombies. From the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy website: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/zombies/. Accessed March 13, 2017.

Philosophical Zombie. From the Wikipedia website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophical_zombie#Types_of_zombies. Accessed March 13, 2017.

This episode was first aired on March 16, 2017