Description of Arts and Crafts

Today, saving arts and crafts. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

How do you preserve the methods and techniques of an art or craft -- the secrets of mixing paints on a palette or shaping clay on a potter's wheel? Nowadays you can at least make videos of artisans explaining their work while they do it. But in the early 1700's in France, long before the invention of photography, scholars grappled with this question.

The members of the French Royal Academy of Sciences gloried in the achievements of the artisans and artists of their time, but since the training was private and through apprenticeships, they worried about the potential loss or degradation of these skills. In 1699 they came up with the idea of preserving in words and pictures all the materials, tools, and operations involved in every craft of the time. A 1733 summary of the project proclaimed that, "By this means, an infinity of practical methods, full of skill and inventiveness, but unknown to the general public, will be drawn out from the shadows." The series title translates as Descriptions of Arts and Crafts. Today we think of arts and crafts as marginal past times or hobbies. But in the 18th century arts and crafts covered the whole world of technology and production.

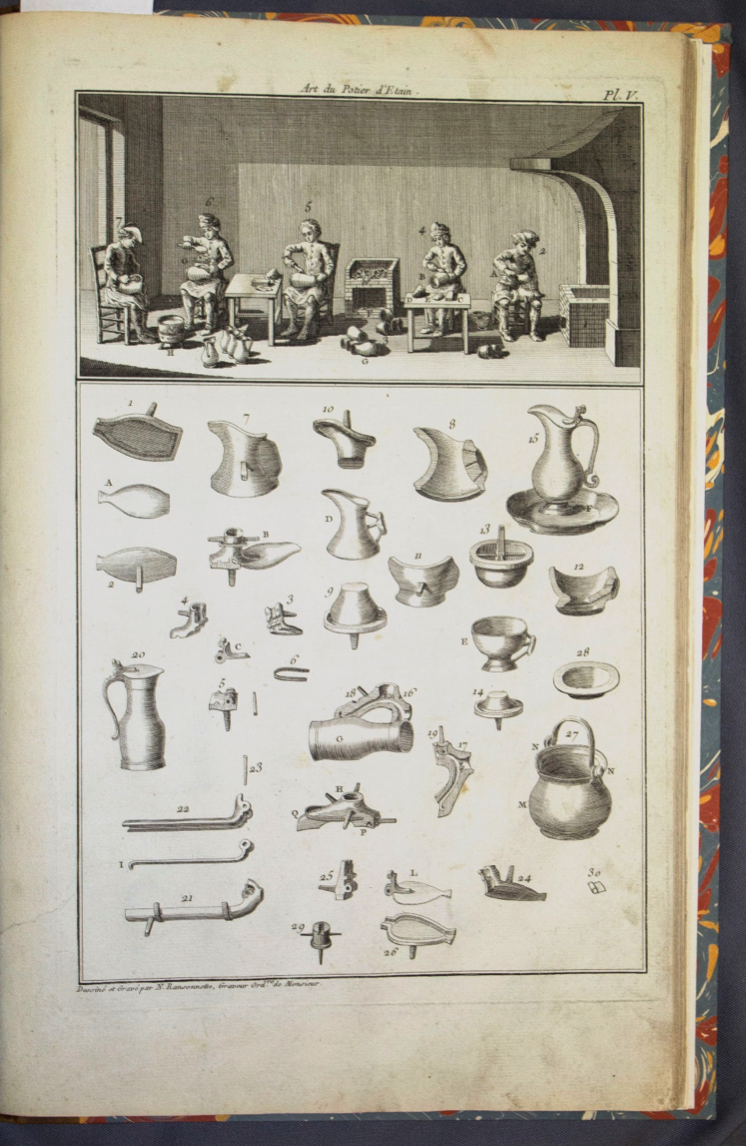

Pierre Nicholas Ransonnette. Engraving and finishing pewter objects from Plate 31, Art du potier d'étain. Photo Credit: Kitty King Powell Library, Bayou Bend Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Of course this was a massive, and expensive, undertaking, and it took years. The first volume did not appear until 1761, and the last was published in 1788, on the eve of the French Revolution. The series covered 73 different subjects, including the making of iron, bricks, tile, leather, paper, and saddles. The more famous encyclopedia of Diderot could not compare in its level of detail on these subjects, but it covered a much wider range of subjects. But both works sprang from a similar desire to document and celebrate human accomplishments.

In Houston, Bayou Bend owns a copy of the volume on making pewter. In the 18th century kings and queens may have eaten off silver platters, and the poor ate from wooden bowls, but just about everyone else used pewter, an alloy of tin with small amounts of lead and copper. This volume covers all aspects of making and finishing pewter objects in 152 pages of small print. The painter and engraver Pierre Nicolas Ransonnette drew and engraved 32 pages of illustrations, which present tools, pewter objects, and fascinating views of the artisans in their workshops.

Pierre Nicholas Ransonnette. Plate 5, Art du potier d'étain. Photo Credit: Kitty King Powell Library, Bayou Bend Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Today's books on the history of pewter still include copies of these illustrations, for no other publication of the period provides so much reliable detail. This volume certainly justifies the original goal of the Academy members when they wrote, "Posterity can thus be assured of the crafts, at least as they exist among us now. It will always be able to rediscover them by turning to this collection."

I'm Margaret Culbertson at the Bayou Bend Collection, where we too are interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Cole, Arthur H. and George B. Watts, The Handicrafts of France as Recorded in the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers 1761-1788. Boston: Baker Library, Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration, 1952.

Salmon, M. Art du potier d'étain. Paris: "Chez Moutard", 1788.

This episode was first aired on October 25, 2016