The Video Game Crash of 1983

by Andrew Boyd

Today, a video game. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In 1982, twenty-five year old Howard Scott Warshaw found himself aboard a Lear jet on his way to meet acclaimed film director Steven Spielberg. Warshaw, a boy-genius video game designer, worked at Atari. His mission was to secure the rights to make a new video game, a game based on Spielberg's latest film E.T. the Extraterrestrial.

The Atari 2600, a video game console released by Atari in 1977. Photo Credit:Wikimedia Commons

Warshaw got the okay. But with Christmas looming he had just five weeks to design and code the game. Bright, energetic, and a bit cocky, Warshaw charged ahead. The market for video games played on home consoles was growing like never before. Space Invaders. Pac Man. Dozens of titles were making their way from video arcades into the home. And new games created just for home consoles were popping up daily. While the market was crowded with competitors, Atari was the clear leader and at the time one of the fastest growing companies in America.

On Christmas day hundreds of thousands of children awoke to find an E.T. video game under their trees. But their joy quickly turned to disappointment. Watching E.T. fall into hole after hole in his search for a phone simply wasn't much fun. Critics panned the game as convoluted, inane, and dull. Needless to say, it didn't catch on. Of the four million game cartridges shipped to retailers, three-and-a-half million were returned to Atari. Such statistics helped make a case that E.T. was the worst video game of all time.

A screen shot from the E.T. Atari game. Photo Credit: Wikipedia Image

But what cemented the game's horrific reputation was timing. For the two years following its release, revenues from all home video games plummeted. From an industry-wide peak of 3.2 billion dollars, revenues dropped to an estimated 100 million -- an astonishing 97 percent slide. Atari and countless other companies never recovered.

Photo Credit: New York Times

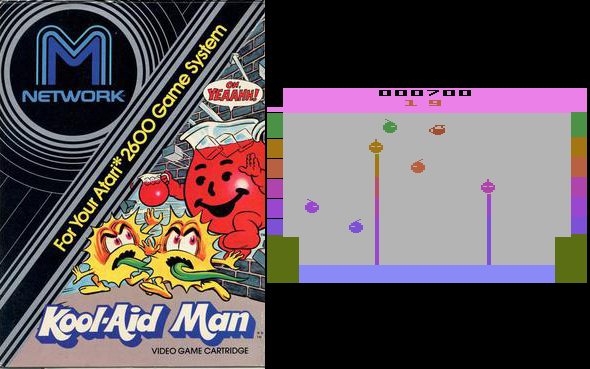

So what happened? Changing technology certainly contributed. Some gaming demand was shifting from consoles to newly popular home computers. But the biggest culprit appears to have been a flood of poor quality games. Game development tools were primitive by today's standards, limiting the creativity of designers. And product makers of all stripes saw a cheap new way to advertise. For instance, Kool-Aid created a game in which the Kool-Aid man sought to quench the "thirsties" -- round, pixilated globs that were trying to empty a swimming pool. It's not hard to imagine why the gaming public grew disenchanted. Many industry pundits were ready to write off home video games altogether, referring to them as a passing fad.

The Kool-Aid Man Atari game, with a screen shot of the Kool-aid man battling the thirsties. Photo Credit: Left Wikimedia Commons Right Wikipedia Image

Of course, such predictions were wrong. By 1985 the industry was being resurrected thanks to two running, jumping Italian plumbers named Mario and Luigi. Still, it's amazing to realize how one of today's wildly successful technology industries stumbled so badly in its formative years.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

B. Kanner. "Can Atari Stay Ahead of the Game?" New York Magazine. August 16, 1982, 13-17.

N. Oxford. Ten Facts About the Great Video Game Crash of '83. From the IGN website: http://www.ign.com/articles/2011/09/21/ten-facts-about-the-great-video-game-crash-of-83. Accessed January 4, 2016.

North American Video Game Crash of 1983. From the Wikipedia website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_American_video_game_crash_of_1983. Accessed January 4, 2016.

This episode was first aired on January 7, 2016