Lees Ferry

by Andrew Boyd

Today, a country divided. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In the mid nineteenth century the Mormons had a problem. Following decades of violent persecution, church members arrived in the Utah Territory where they established a firm foothold in present day Salt Lake City. From there the community began to expand into neighboring lands, both to accommodate the steady influx of the faithful and to fulfill the church's mission of proselytization. And as missionary settlers headed south they encountered a major obstacle: the Colorado River.

When we think of the Colorado River our thoughts naturally turn to the Grand Canyon. Over 18 miles wide and over a mile deep in places, it's well deserving of the title "grand." But an often overlooked dimension is its length. And not just of the canyon proper, but the miles of inhospitable river gorge that extend upstream and to the east.

Mojave Point with Rim. Photo Credit: National Park Service

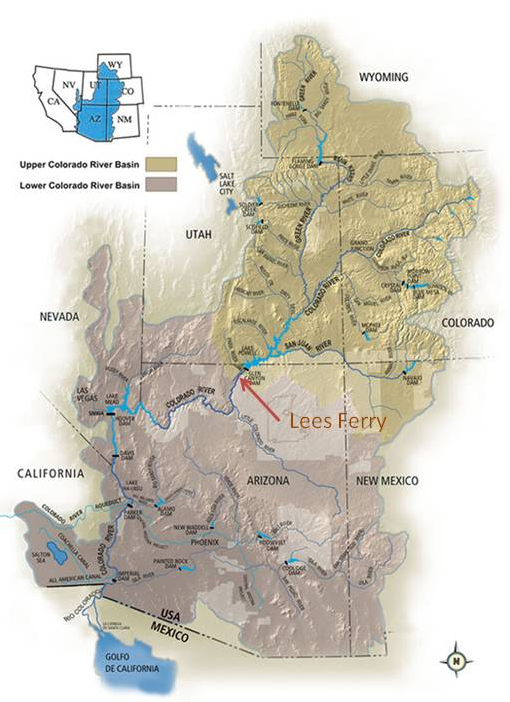

You might expect that somewhere along the way there'd be a good place to cross; a place where both sides of the river could handle horses and wagons. But stretching from Nevada all the way through Arizona, Utah, and into Colorado, that's really not the case. With only a couple of exceptions there's nowhere to cross. And even those spots are far from ideal. Reality is, the Colorado River is a giant, natural fence.

An overhead map detailing the Colorado River and Lees Ferry Photo Credit: Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program

The most important exception is a location now known as Lees Ferry, situated upstream of the Grand Canyon but below Glen Canyon and the Canyonlands. Here the river's no more than a stone's throw across and free of rapids. And in 1864 Mormon settlers made their first crossing: fifteen men, their horses, and supplies. A few years later, Mormon leader John D. Lee joined Brigham Young and Major John Wesley Powell on an expedition that led to Lee being chosen to establish a regular ferry crossing. The crossing's remote location had the advantage that it shielded Lee from prosecution in his alleged involvement in the massacre of 120 non-Mormons who were migrating westward. Seven years after arriving at the ferry outpost, authorities caught up with Lee, and he was tried and executed for his crime. But the location of the river crossing still bears his name, though the ferry has long since been replaced by a bridge.

Lees Ferry. Photo Credit: National Parks Service

And for all our technological expertise, the Colorado River still stands as an obstacle for overland travel. In the more than 500 miles of river stretching east from the Hoover Dam in Nevada, bridges can be found in only three locations. And if you're interested in rafting the Grand Canyon be prepared to make a commitment. Expeditions put in at Lees Ferry, and the next river stop with road access of any kind is some 224 miles downstream. It seems nature's engineering won't allow for a brief encounter. And given the grandeur of the surroundings, that seems only appropriate.

A series of photos of Lees Ferry Photo Credit: E. A. Boyd

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Note: The bridges that cross the Colorado River in the 500 miles east of the Hoover Dam can be found near Lees Ferry and Page, Arizona, and near Hite, Utah. Limited seasonal ferry service can be found at locations on Lakes Mead and Powell, and a foot bridge connects the north and south sides of one of the deepest points of the Grand Canyon in Grand Canyon National Park.

Lees Ferry History. From the National Park Service website: http://www.nps.gov/glca/learn/historyculture/leesferryhistory.htm. Accessed October 21, 2015.

This episode was first aired on October 22, 2015