Walden

by Andrew Boyd

Today, a book report. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

It caught my attention while wandering the aisles of Auntie's Bookstore, an eclectic yet well stocked establishment in the Pacific Northwest. I was in search of summer reading and wasn't sure what I wanted. Science essays? Perhaps a biography. Then I saw it: Henry David Thoreau's Walden.

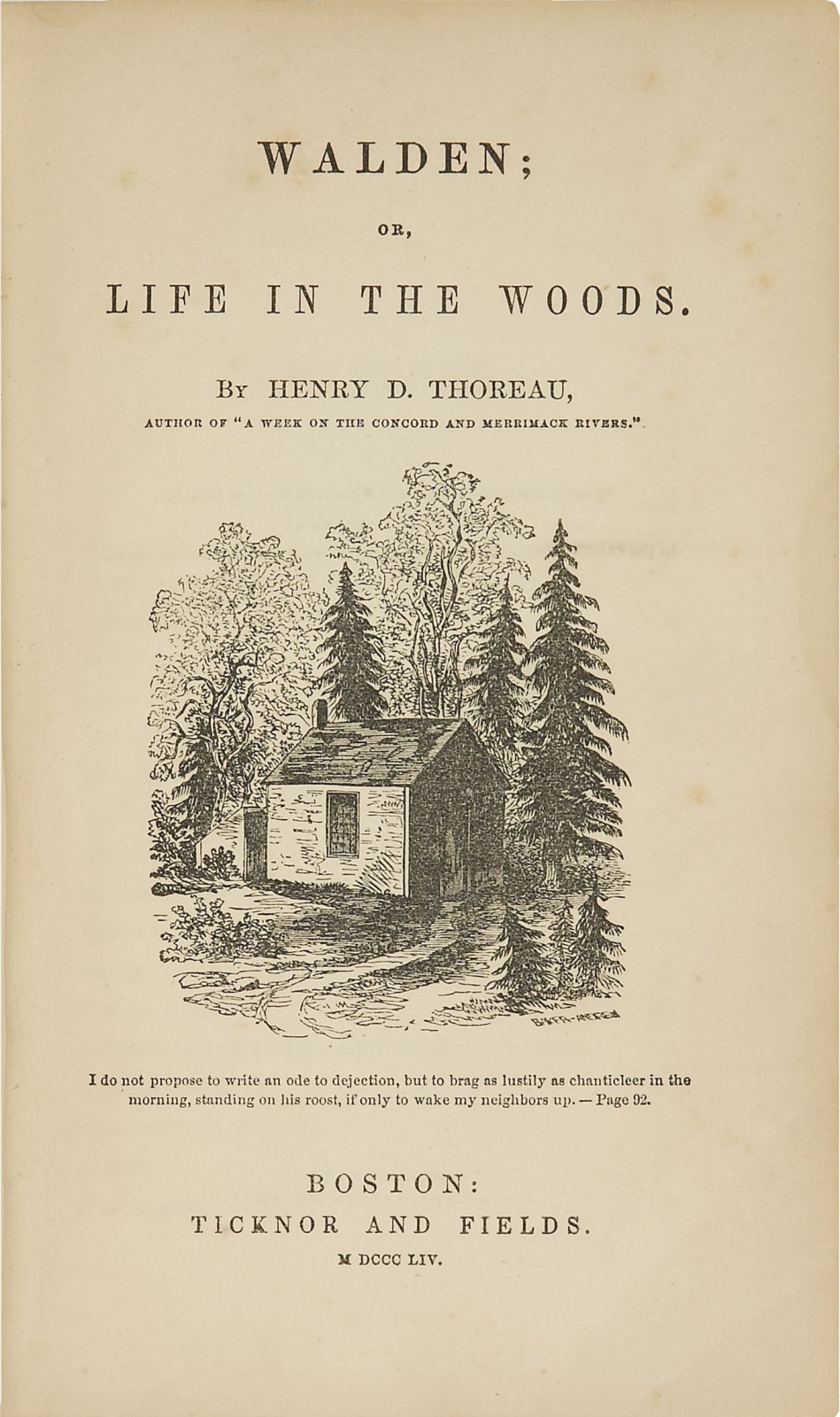

Title page from first edition of Henry David Thoreau's Walden (1854). Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Admittedly part of the attraction lay in the thought of immersing myself in its pages while on the shores of a quiet mountain lake. Where better to read Thoreau's chronicling of his soul-searching stay on Walden Pond?

Walden's mountain lake Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Thoreau has long held a fascination with people in all walks of life, from rebellious students to literary scholars. John Updike brilliantly summarized things. "Walden has become such a totem of the back-to-nature, preservationist, anti-business, civil-disobedience mindset, and Thoreau so vivid a protester, so perfect a crank and hermit saint, that the book risks being as revered and unread as the Bible." I didn't know enough to revere it, but I wasn't going to leave it unread.

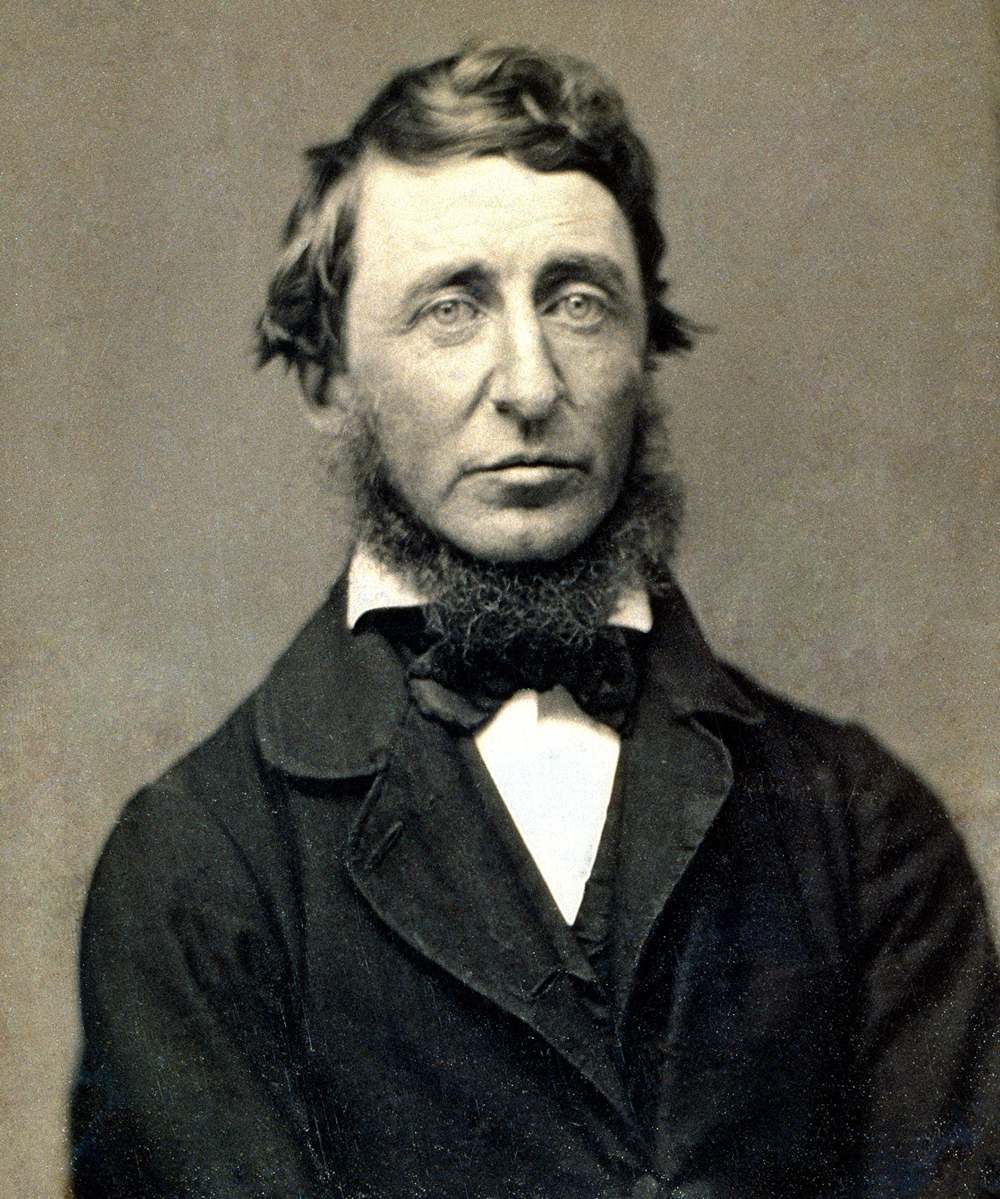

Portrait photograph of Henry David Thoreau. Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

And what I found in its pages surprised me. It's true that Thoreau delighted in nature. "This is a delicious evening," he wrote after taking a walk, "when the whole body is one sense, and imbibes delight through every pore." He embraced time to himself. "I never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude." But he also wasn't averse to technology. He often signed "civil engineer" after his name. But his acceptance of technology came with one giant caveat.

Technology had improved humankind's lot by presenting more effective means of providing the food, clothing, and shelter necessary to live. Thoreau's caveat was the line he drew between necessity and extravagance. "Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity!" he cried out. "Men have become tools of their tools." And these tools, he believed, stood between us and the transcendentalist lifestyle he wished for all.

Thoreau's message is contemplative, but not dour. The prose draws the reader in; his prods at society are as humorous as they are pointed. "We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas," he wrote. "But Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate." "For my part, I could easily do without the post office. I think there are very few important communications made through it." Thoreau may well get his wish regarding the post office, but not for the reasons he'd hoped. Email. Facebook. Twitter. Incessant interruptions by our smart phones. Thoreau would surely consider them a hell of our own making.

It's hard to argue with Thoreau's message. Even as an engineer who revels in technology, I have regular need to take to the woods to hear myself think. I enjoyed my time with Thoreau, though I have to admit, half of my reading was on the plane. And no, the irony was not lost.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

For a related episode, see THOREAU'S PENCILS.

J. Updike. 'A Sage for All Seasons.' The Guardian, June 25, 2004. See also: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2004/jun/26/classics. Accessed September 14, 2015.

H. D. Thoreau. Walden; or, Life in the Woods. 1854. Reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1995.

This episode was first aired on September 17, 2015