The Pennsylvania Prison System

by Andrew Boyd

Today, in the pen. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

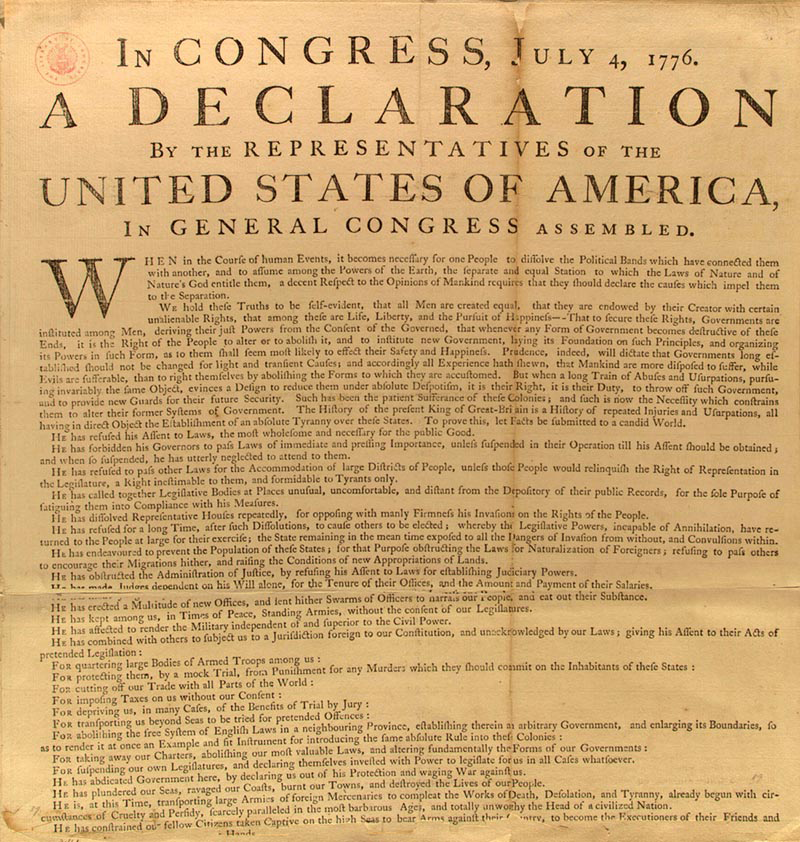

The U.S. was born of revolution; of "the rockets' red glare" and "bombs bursting in air." But it was also born of something far more sacred to American values: the ideals of the Enlightenment. Those ideals included the self-evident truth that all people are created equal and "endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights." So what was a young nation to do when it came to the rights of those in jail?

The Declaration of Independence Photo Credit: Library of Congress

Prisons have never been very nice places, and that remained true in the U.S. following the Revolutionary War. Prisons were basically holding pens designed to keep miscreants off the street. Men, women, and children were thrown together. Rape and robbery were common among prisoners. Jailers made less effort to protect than to profit from inmates' misfortunes.

Such were conditions in the Walnut Street Jail, located directly behind Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Conditions hadn't always been that way in the City of Brotherly Love. Early jails benefitted from the Quaker precepts of the first settlers. But by the time the Declaration of Independence was signed, the city's rapidly growing prison population had led to the system's decay.

In the aftermath of the Revolutionary War the appalling conditions received new attention, especially by a man named Benjamin Rush. Encouraged by his friend, Ben Franklin, Rush travelled to France where he spent time rubbing shoulders with French intellectuals. He returned to Philadelphia fresh with ideas about how to reform the prison system.

At the heart of Rush's philosophy was the concept of crime as a moral offense. This led him to conclude that prisons should be houses of atonement and redemption — of penitence. This in turn gave rise to the name penitentiary.

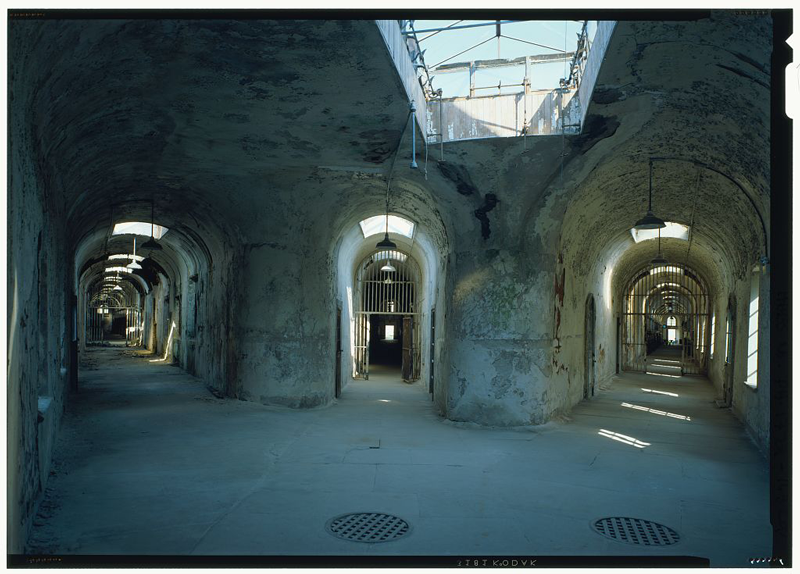

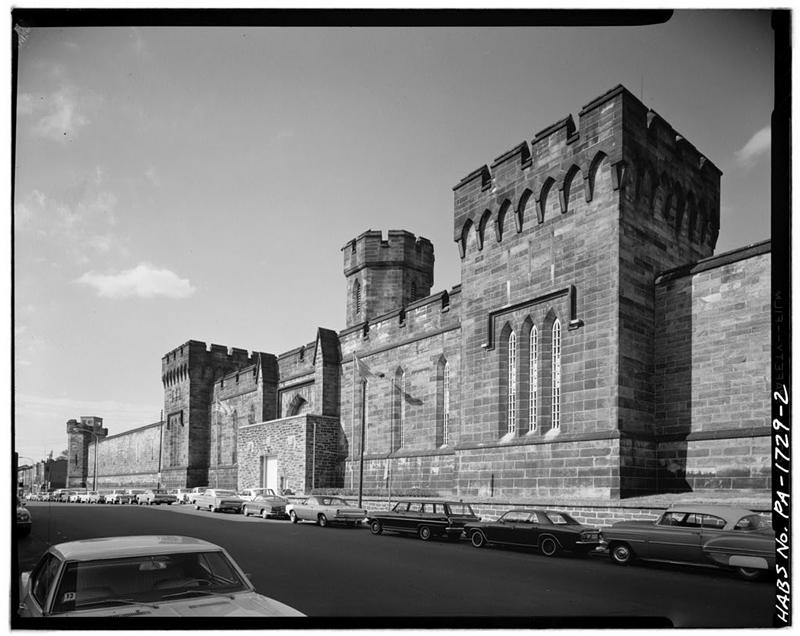

The first step in reform was to create humane conditions, which itself was a huge breakthrough. But for true repentance to occur, Rush argued in favor of isolating prisoners. A new prison was built to replace the Walnut Street Jail, complete with flush toilets and shower-baths in each private cell, luxuries that not even President Andrew Jackson could enjoy at the White House. Such treatment, however, came at a tremendous price. Inmates were locked in their cells for the duration of their stay — frequently years at a time — with minimal human contact and nothing more to read than a bible.

Empty hallways of the Eastern State Penitentiary. Photo Credit: Library of Congress

A decrepit stairwell at the Eastern State Penitentiary. Photo Credit: Library of Congress

Eastern State Penitentiary. Photo Credit: Library of Congress

The penitential nature of the new prison was praised by many, and worldwide over 300 prisons were built on the Pennsylvania model. Many others viewed the model as nothing short of cruel. In the end, the prison in Philadelphia ceased using solitary confinement for the simplest of reasons: overcrowding. Just as growing prison populations led to the demise of the Quaker system, so, too, did overcrowding serve as the bell toll for Benjamin Rush's penitentiaries.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

For a related episode, see BENJAMIN RUSH.

The Declaration of Independence: A Transcription. From the website of the U.S. National Archives: http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/declaration_transcript.html. Accessed March 31, 2015.

C. Woodham. Eastern State Penitentiary: A Prison with a Past. From the Smithsonian.com website: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/eastern-state-penitentiary-a-prison-with-a-past-14274660/?no-ist. Accessed March 31, 2015.

This episode was first aired on April 2, 2015