Cataclysm

by Andrew Boyd

Today, a river runs through it. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In 1923, J Harlen Bretz rocked the slow-grinding geological establishment. Bretz had been studying the Columbia River Plateau, a vast area covering large parts of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, when he noticed something strange. The deep gorges carved into the landscape weren't typical of slow erosion. Instead, they showed signs of catastrophic flooding — signs that torrential waters had ravaged the land.

Geologist J Harlen Bretz (Dr. Julian Goldsmith/Wikimedia)

Bretz' theory met strong, even ugly, opposition from the geological community. He was a little known researcher from the west whose forceful mannerisms could be off-putting. He also had one big hole in his theory: where did the flood waters come from? In the end it didn't prove such a big hole, but it took more than ten years for the story to take shape.

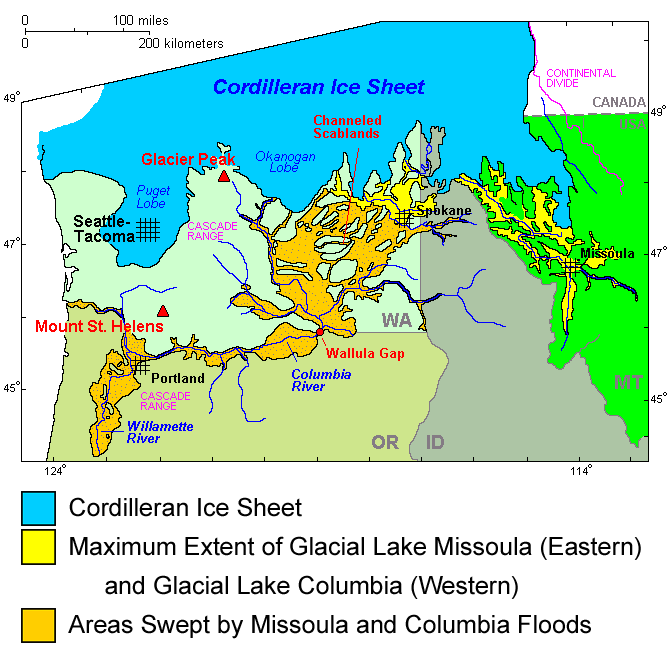

The massive ice sheets formed during earth's most recent ice age peaked around twenty-two thousand years ago. One, the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, stretched from the arctic to the state of Washington. As the sheet advanced it created glacial ice dams which in turn formed inland lakes, some rivaling the size of the Great Lakes. But the ice dams couldn't last forever. And when they collapsed the results were often cataclysmic.

Map of the Missoula Floods USGS/Wikipedia)

The greatest flood occurred roughly fifteen thousand years ago when the Glacial Lake Missoula broke free. In as little as forty-eight hours, water equal to the combined volume of Lakes Erie and Ontario ripped through a canyon near the Washington/Idaho border. The water poured out into central Washington covering thousands of square miles. Boulders were tossed about like pebbles in flood waters that at times exceeded sixty-five miles per hour. The water ultimately made its way to the Pacific Ocean, but not before covering what is now Portland, Oregon in several hundred feet of water. A cliff now called Dry Falls, located in Washington's Grand Coulee, saw its share of the flood water. Five times longer and more than twice as high as Niagara Falls, Dry Falls is thought to have been the world's largest known waterfall, if only fleetingly.

An aerial view of Dry Falls (Paul L. Weis and William L. Newman/Wikimedia)

In reality, many cataclysmic floods occurred as the Cordilleran Ice Sheet wrestled with the land. Geologists now believe the floods numbered in the hundreds. But the questions of where, when, and how big they were remain largely unanswered. You can see the evidence for yourself on the Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail, a trail established by Congress in 2009.

And what of J Harlen Bretz? As evidence mounted his reputation was secured. But it wasn't until 1979, at the age of ninety-six, that Bretz received the Penrose Medal, the top prize awarded by the Geological Society of America. Bretz clearly felt vindicated, but had one regret: none of his detractors were alive for the ceremony.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Notes and references:

Dry Falls. From the Wikipedia website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dry_Falls. Accessed June 17, 2014.

Megafloods of the Ice Age. From the NOVA website: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/earth/megafloods-of-the-ice-age.html. Accessed June 17, 2014.

Missoula Floods. From the Wikipedia website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Missoula_Floods. Accessed June 17, 2014.

This episode first aired on June 19, 2014.