Hayek and the Mind

by Andrew Boyd

Today, a man who crossed over. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

One of the most hotly debated issues in twentieth century economics was the role of government: should it seek to actively control free markets or not?

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Friedrich Hayek was one of the few outspoken advocates of leaving markets alone. His message largely fell on the deaf ears of policy makers at the time, but he influenced generations of future economists. By the late twentieth century his name was all but synonymous with free market advocacy.

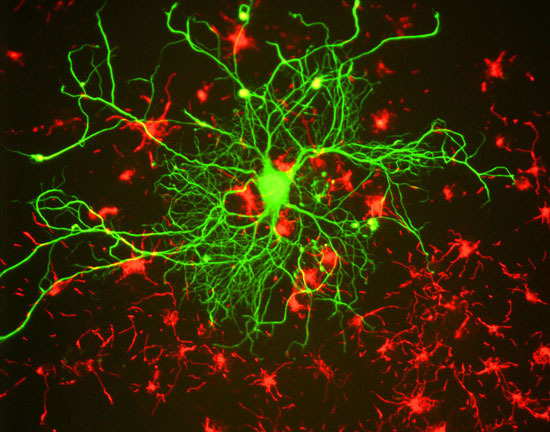

Hayek eventually won the Nobel Prize in Economics. But today we look at a different aspect of the man; an aspect far removed from the economy. The very beginning of Hayek's career was spent working in the lab of an anatomist, where Hayek was quite literally exposed to the inner workings of the brain. The experience led to a paper entitled, "Contributions to a Theory of How Consciousness Develops." It wasn't published and would've been lost to time if it weren't for the fact that Hayek picked up the topic again almost a quarter of a century later. In his book The Sensory Order, Hayek expanded on issues related to the mind, brain, and senses. When the work was published in 1952, Hayek considered it 'the most important thing I have yet done.' That's saying a lot given his most famous economic contributions were already behind him.

Like most scholars of his day, Hayek believed inner conscious feelings arose from events outside the body. How I feel when I watch a sunset is a result of the sights, sounds, and smells that I encounter through my senses. Where Hayek differed from prevailing orthodoxy was in the role of the body. The body changes from day to day, rewiring itself based on what an individual experiences. Thus, if someone could observe an absolutely identical sunset weeks after the original, the inner conscious experience could be quite different because the person was different. Today, that's a widely held belief by many in the scientific community.

Typically when scholars veer this far afield their reputation suffers. Hayek's case was a bit different in that the work was largely ignored. But not forever. As time cemented Hayek's economic legacy, scholars found themselves looking more seriously at his entire body of work. And what they found was surprisingly clairvoyant. Hayek put forth theories about the functioning of the brain and the philosophy of mind that hadn't been explored until recently. History's now giving him some credit, attaching his name to ongoing work in neuroscience and philosophy. Not bad for an economist.

These days it's rare to see a scholar who's made contributions in more than one narrowly defined field. In that context Friedrich Hayek's story is a welcome change.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

B. Caldwell. 2004. 'Some Reflections on F. A. Hayek's The Sensory Order.' Journal of Bioeconomics, vol. 6, pp. 239-254.

F. Fukuyama. 'Friedrich A. Hayek: Big-Government Skeptic.' New York Times Book Review, May 6, 2011. See also the New York Times website: https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/08/books/review/f-a-hayek-big-government-skeptic.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1. Accessed August 1, 2013.

S. Nasar. Friedrich von Hayek Dies at 92: An Early Free Market Economist. New York Times, March 24, 1992. See also the New York Times website: https://www.nytimes.com/1992/03/24/world/friedrich-von-hayek-dies-at-92-an-early-free-market-economist.html. Accessed August 1, 2013.

The Social Science of Hayek's The Sensory Order. Advances in Austrian Economics, vol. 13. W. N. Butos, ed. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2010.

The picture of the neuron is from Wikimedia Commons. The picture of the Seattle sunset is by E. A. Boyd.

This episode first aired on August 8, 2013.