Empty Shipping Containers

by Andrew Boyd

Today, empty boxes. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

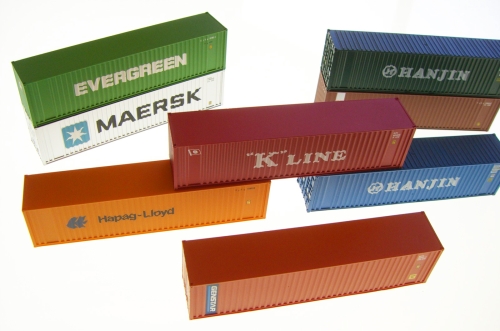

It's impossible to overstate how shipping containers have changed our lives — those colorful metal boxes about the size of truck trailers. Shipping costs have dropped to a mere fraction of what they used to be.

Shipping containers didn't exist in 1950. Today, roughly seventeen million travel the world on ships, trains, and trucks. Laid end to end, they'd stretch around the globe almost four-and-a-half times. Managing their movement is an engineering feat in its own right. It's work enough transporting a full container to its destination. But then comes another question — what to do with the empty?

New shipping containers cost about two to three thousand dollars. That makes them too expensive to simply throw out. In the best of all possible worlds we could refill them and send them back where they came from: iPads from China to the U.S., seeds from the U.S. to China. Unfortunately, the U.S. imports far more than it exports. For every hundred containers that enter the U.S., fully half will leave empty. Another forty-five will sit idle in a container yard, waiting for something to carry. That leaves just five that are spoken for.

In China, where demand outweighs supply, the situation's reversed. It's not uncommon to see entire containerships chartered just to bring empty containers into the country, a country that's home to seven of the world's eleven largest container ports. China also produces virtually all of the hundred thousand or so new containers manufactured every year.

Worldwide, containers spend only one-third of their lives filled with cargo. That seems wasteful. So it's been proposed that, rather than shipping empty containers, they be made into housing — build a container, ship a container, repurpose a container. The idea's received a lot of attention in some circles, and many of the home designs are as stunning as they are functional, giving rise to the term "containertecture." It's an exciting idea; the possibility of ending homelessness while simultaneously stopping all that wasted container shipping.

Unfortunately, the economics don't favor the housing option. Though shipping containers are nothing more than empty metal boxes, they have value just like cars and boats. And like cars and boats there's an active market for them. A quick visit to ebay and you'll find containers for sale in all colors and sizes. (Needless to say they're easy to ship.) If it made economic sense, you'd see container houses popping up everywhere. So far, that's not the case. Shipping empty containers around is more economically viable.

The idea for inexpensive housing may yet catch fire among international aid agencies and regional governments. And with all the creative minds at work on design, who knows what the future holds? Until then, we'll just have to appreciate shipping containers for what they are: great big colorful boxes.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Notes and References:

Thanks to Dr. Jean Krchnak of the University of Houston College of Architecture for suggesting the topic of this essay.

For a related episode, see THE BOX.

For some innovative container home designs, see http://www.mnn.com/your-home/remodeling-design/photos/8-eye-catching-shipping-container-homes/a-new-kind-of-living. Accessed April 30, 2013.

Home page of the World Shipping Council: http://www.worldshipping.org/. Accessed April 30, 2013.

J. Rodrigue. The Geography of Transport Systems. New York: Routledge, 2013.

The first two pictures are from Wikimedia Commons. The remaining pictures are from the flickr website.

This episode first aired on May 2, 2013.