How Many Wings or Strings?

Today, How many wings or strings on an aeroplane or a violin? The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run and about the people whose ingenuity created them.

Choosing the right number of wings or strings is a long and curious process. Look at how the history of flight divides into completely different eras -- before and after WW-II. First was one of wild experimentation, trying to get the right combination of elements. We spent the generation after the Wright Brothers trying out every possible arrangement of wings, engines, and bodies.

Trial and error finally led to optimal airplane forms. Very few biplanes made it into WW-II. We generally put one engine on the front of small monoplanes. Or we put two or four engines on the single wing of larger planes. When we added jet engines in the wake of the war, things changed rather little. We soon settled on single-winged planes with one to four jet engines.

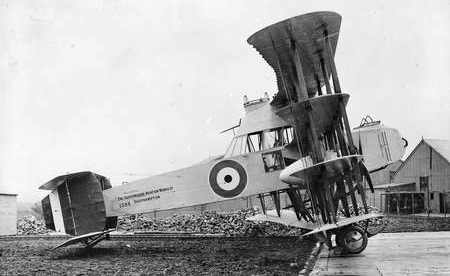

The Supermarine PB31E, Nighthawk, 1917. This lumbering quadriplane, intended to attack German dirigibles, proved hopelessly inadequate for that job. Its top speed was 75 mph and it took a full hour for it to reach an altitude of 10,000 feet. It was one of hundreds of failed experiments in the early era of flight.

We could play this game with any number of technologies. Take the violin family. It found its finished form in the early 18th century. The 19th century saw violin necks lengthened a bit -- then metal strings replacing gut. Still, that's about all that changed.

But, from the medieval rebec onward, all kinds of bowed stringed instruments had risen and fallen. The Amati family began evolving the modern violin in the mid-16th century. They were followed by the Guarnaris, then the Stradavaris. The 4-stringed violin, as we know it, was in place when the last great makers from these families flourished in the 1730s and 40s. Other forms, like the six or seven stringed viola d'amore lasted a few more decades. But it faded away just as biplanes faded in the late 1930s.

Now, we only occasionally see a biplane or trimotor. When we hear a viola d'amore or gamba, it's an arcane treat.

Technologies do mature, just as people do. Yet, unstable youth is what's really exciting. Not many people know that, during WW-I, Fokker built his triplane in an attempt to surpass Sopwith who'd already built a pretty effective triplane. Or that Fokker went on to try building a fighter plane with five wings?

All those planes were meant to be very maneuverable in combat, but they were hard to fly. The famed Red Baron flew his triplane only toward the end. And he was soon killed in it.

It was likewise an exciting time when violin makers multiplied strings, added sympathetic strings, and created beautiful nightmares of complexity. In the end, the clean 4-stringed violin family emerged with a shape that no one has been able to dislodge.

A seven-stringed LeClerc Viola d'Amore with a second set of seven sympathetic string below the main strings. This late instrument was made in 1770.

As we invent, we eventually get things right and are left with nowhere else to go. Call that the bittersweet smell of success. But we keep trying: Violin makers still offer new forms. Inventors try to surpass the old snap mousetrap or gem paperclip. One of those Quixotic inventors might yet manage to make a radically better violin, airplane, or paperclip. It'd be a delicious surprise if one actually did. But it would be a surprise.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

A great deal more can be learned from the various Wikipedia entries on any of these items that I've mentioned. I also like to relevant background on the various items in the text above. Speaking of odd early aircraft, check out this YouTube movie of the assymetric Blohm & Voss BV 141 in flight.

This episode was first aired on March 6, 2013