Coffee Houses

Today, let's share a cup of coffee. The University of Houston's Department of History presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

As I savor a latte at my favorite coffee establishment, I look out over my fellow caffeine lovers. A few people chat quietly. Many, like myself, sip their brew alone in front of their laptops or iPads. Soothing music plays in the background. A common scene in a coffee house today, but a far cry from the vibrant and highly political origins of this familiar gathering place.

Coffee houses may seem like a relatively new thing. But their origins are much older, going back four centuries or more. We first find coffee in the historical record about a thousand years ago; the first recorded mention of a coffee house comes from Constantinople around 1555. As trade between East and West grew, Europeans became increasingly aware of the aromatic beverage. Entrepreneurs in London smelled opportunity: people would spend their money on this exotic import. The London coffee house was born.

A Turk employed by an English merchant to the Middle East established the first coffee house in London in 1652. People flocked to his shop, and soon dozens more coffee houses sprang up around the city. Within a decade or two, coffee began to give English ale a run for its money as the social drink of choice.

A wood cut of a 17th-century London coffee house.

But these early coffee houses were not without controversy. Supporters saw coffee as a healthful, non-intoxicating alternative to beer. Detractors condemned it as a dangerous foreign substance, contributing to corruption and even impotence in Englishmen. More concerning to those in power, coffee houses had quickly become gathering places for people to share news and, perhaps, spread sedition.

To attract customers, coffee houses stocked newspapers and political pamphlets, providing fodder for conversation. They buzzed with people making deals, swapping stories, and talking politics. In a world where speech was not free and censorship was the norm, coffee houses offered a relatively open public space. Government saw this as dangerous. In 1675, King Charles II issued a royal proclamation suppressing all coffee houses. This proved hugely unpopular, and ultimately unenforcible. Coffee houses had become too important to disappear with a flick of a king's pen. They multiplied in England, and, crossing the Atlantic, percolated to America, too.

Additional proclamation against coffee houses by Charles II, 1676.

Coffee houses were not just for politics. People of all sorts and social levels discussed literature, theology, and new scientific developments. In a coffee house, aristocratic members of the Royal Society might discuss botany with working gardeners.

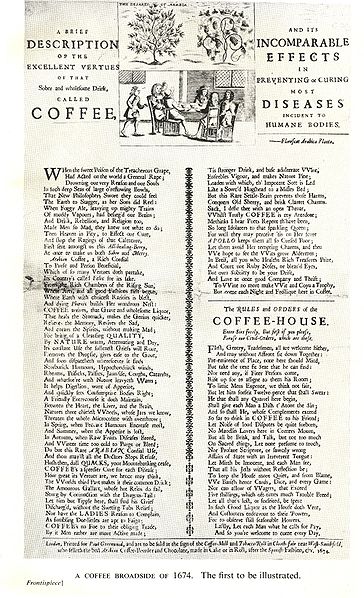

A coffee broadside from 1674.

Coffee houses offered what few other institutions of that time did: a space where ideas could be debated by the wider public. So as we today sip our lattes, read the newspaper on line, and check out our favorite political blog, we are heirs to a public sphere that coffee helped create.

I'm Cathy Patterson at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Cathy Patterson is Associate Professor of History and Associate Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Houston. She is author of Urban Patronage in Early modern England: Corporate Boroughs, the Landed Elite, and the Crown, 1580-1640 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999).

Sources:

Anthony Clayton, London's Coffee Houses: A Stimulating Story (London: Historical Publications, Ltd., 2003).

Markman Ellis, The Coffee House: A Cultural History (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2004).

Steven Pincus, ''Coffee Politicians Does Create': Coffeehouses and Restoration Political Culture', The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 67, No. 4 (Dec., 1995), pp. 807-834.

M.P., The Character of Coffee and Coffee Houses (London, 1661).

Images in the order they appear:

Ukers, William H. "Chapter X: The Coffee Houses of Old London." All About Coffee.

Accesssed by: http://clickherefordigitalhumanities.wordpress.com/category/history/.

In the public domain. Accesssed through Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Rulesandorders.jpg.

This episode was first aired on December 5, 2012.