Seattle's Floating Bridges

by Andrew Boyd

Today, Homer Hadley's folly. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

When Homer Hadley first made his proposal in 1921, it was met with such skepticism by civic leaders, newspapers, and lenders that he was forced to shelve it. But his idea didn't go away. Ten years later, it found its way into the hands of Lacey Murrow, brother of world famous broadcast journalist Edward R. Murrow and, more importantly, head of the Washington State Department of Highways. Lacey Murrow liked Hadley's idea. Construction began in 1939, and just a year later the Lake Washington Floating Bridge opened to traffic.

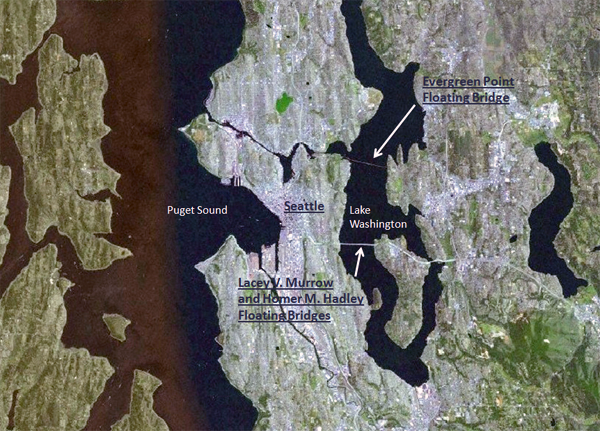

The city of Seattle sits on a long strip of land bordered on the west by the Puget Sound and on the east by Lake Washington. Driving around the lake to the far side is a trip of about thirty miles. Yet the lake itself is only a mile or two wide. A bridge made sense for the city's expanding population. But why a floating bridge?

Hadley's inspiration came from experience working with concrete ships and barges during World War I. If concrete made good barges, he reasoned, why not string a few together and make a bridge? Further inspiration undoubtedly came from Hadley's affiliation with the Portland Cement Association where he promoted the use of concrete. Lake Washington's depth and soft bed were factors as well, since they made building a conventional suspension bridge problematic.

Hadley's floating bridge was such a success that Washington State adopted the concept for future bridges. Lake Washington is now home to three, and all rank among the five longest floating bridges in the world. In honor of the man who first spearheaded the idea, the third bridge was named after Homer Hadley.

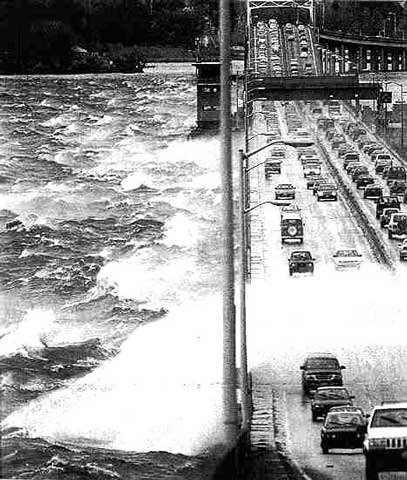

Floating bridges have the advantage that they can't come toppling down in high winds. That's what happened to the infamous Tacoma Narrows Bridge just south of Seattle. But floating bridges have at least one disadvantage that others don't: they can sink.

The Hood Canal Floating Bridge lies thirty miles northeast of Seattle. It's the world's longest floating bridge over an expanse of ocean water. It functioned without incident until a freak winter windstorm in the late seventies brought gusts of up to 120 miles an hour whipping down the canal from the north. The western half of the bridge broke loose and sank. It's since been rebuilt.

Another incident occurred to Hadley's original floating bridge while undergoing renovations. Watertight doors on the concrete pontoons were left open during a heavy rainstorm. The pontoons filled with water and sank. It wasn't one of the engineering world's finest moments. Everything was caught on camera.

But for all their travails, Seattle's floating bridges are part of her mystique. They're a fitting tribute to the watery, wet, Emerald City by the sea.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Notes and references: For more on concrete ships, see episode 2679, THE SS SELMA.

Hadley, Homer More (1885-1967), Engineer. From the History Link website: http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=5419. Accessed November 6, 2012.

Pontoon Bridge. From the Wikipedia website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pontoon_bridge. Accessed November 6, 2012.

Washington: Floating Bridge Capitol of the World. From the Seattle PI website: http://www.seattlepi.com/local/transportation/article/Floating-bridges-of-the-world-2971885.php. Accessed November 6, 2012.

All pictures are from websites of the Washington State Department of Transportation.

This episode was first aired on November 8, 2012