Lobotomy

by Andrew Boyd

Today, science gone wrong. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I stand in awe of what medical research has achieved. From germ theory to the double helix of DNA, we live longer, healthier lives. But sometimes even the most well intentioned efforts by the finest minds can go woefully astray.

Antonio Moniz was a celebrated neurologist practicing in the early twentieth century. He received wide acclaim for pioneering work on imaging techniques of blood vessels in the brain. But his most enduring legacy was the development of a medical procedure called the leucotomy — later known as the prefrontal lobotomy, or simply lobotomy.

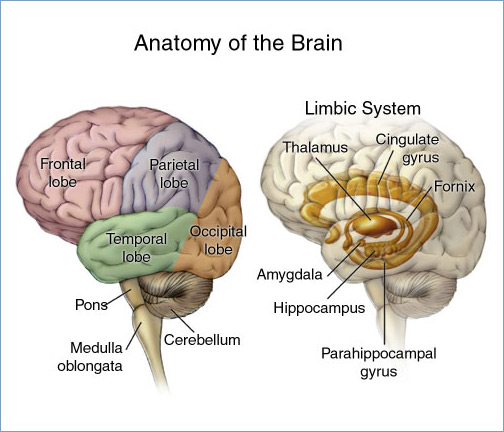

By observing brain damaged patients, neurologists had come to understand the importance of the frontal lobes in higher brain activity — emotions in particular. Experiments suggested that troubled animals could be pacified when connections between the frontal lobes and other parts of their brains were interrupted. A leucotomy is a surgical procedure that severs brain connections to a patient's frontal lobes.

Today, it's horrifying to even imagine. The actual procedure could be barbaric. But at the time it was considered a groundbreaking development, a development for which Moniz received one of the world's highest honors: the 1949 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

In short, the leucotomy appeared to offer hope where none had been before. Antipsychotic drugs weren't available, leaving psychiatric wards few options for dealing with the dangerously disturbed. Nor were antidepressants available, leaving seriously depressed patients searching for anything to improve their lives.

In a widely cited study of twenty patients who received leucotomies, Moniz concluded that one third greatly improved, another third mildly improved, and the remaining patients showed no change. Studies performed by other researchers confirmed Moniz's results.

But of course, we're left to ask by what measures had the patients improved? Did they have a better perspective on life, or were they simply less danger to themselves and those around them? In presenting its award, the Nobel committee acknowledged that the procedure didn't always work as hoped. But in these cases, at least psychiatric care '... will be much simplified by the fact that the patient ' can be kept in a quiet ward.' It's nothing short of bone chilling to hear the prize committee commending a procedure that simplifies patient care by inducing brain damage.

"Frontal leucotomy," reads the transcript of the award ceremony, "... must be considered one of the most important discoveries ever made in psychiatric therapy, because through its use a great number of suffering people ... have been socially rehabilitated." That's certainly not a perspective you'll find today. But it remains an important reminder that in the quest to improve our lives, science has the potential to run wildly amok.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Notes and references:

Award Ceremony Speech for the 1949 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. From the official website of the Nobel Prize: http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1949/press.html. Accessed August 14, 2012.

Z. Kotowicz. 2005. 'Gottlieb Burckhardt and Egas Moniz — Two Beginnings of Psychosurgery.' Gesnerus, 62:77-101.

All pictures are in the public domain.

This episode was first aired on August 16, 2012