Impact Printers

by Andrew Boyd

Today, we don't make an impact. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

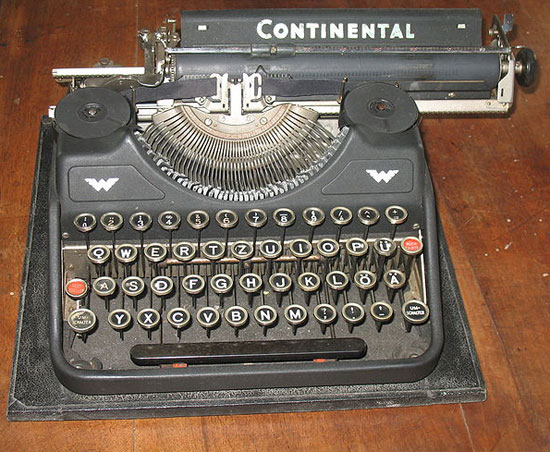

Typewriters are marvelous devices because they're so wonderfully simple. Push a key and a hammer strikes an inked ribbon. In turn, ink is transferred to the paper in the shape of a letter.

[Typewriter audio]

The concept is so natural that the first computer printers worked a lot like typewriters. But as computers evolved, engineers soon began to realize some serious limitations to the typewriter archetype. For one, it was slow. But it also locked the user into a fixed set of characters. Printing basic words was no problem. But what about foreign characters, or mathematical symbols?

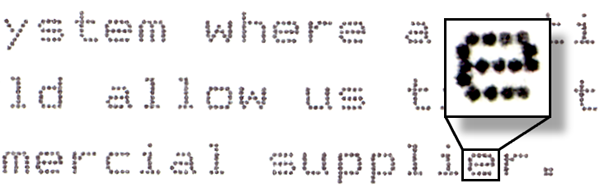

The early seventies saw an important advance with the release of dot matrix printers. They don't work with a fixed collection stamped characters. Instead, they print dots that, when taken together, look like characters. The images aren't perfect, but they form a reasonable approximation.

[Dot Matrix audio]

Dot matrix printers gained in popularity because they were cheap, flexible, and reliable. But the print quality was poor. Individual dots were clearly visible, and the printers were shunned for activities like professional correspondence.

Help was on the way, however. The impact of a major innovation had yet to make its way to market, and that innovation was no impact.

Xerox copy machines don't work by pounding characters onto the printed page. In fact, they don't work with characters at all. Instead, they mindlessly transfer dark spots by melting toner on a blank sheet of paper. It's a completely different approach than that of a typewriter.

The idea of using Xerox copy machines as printers was so novel that even Xerox executives had trouble coming to terms with it — in spite of the obvious profit windfall. They were eventually convinced by a determined engineer. His first prototype of the laser printer was built using an abandoned Xerox photocopier.

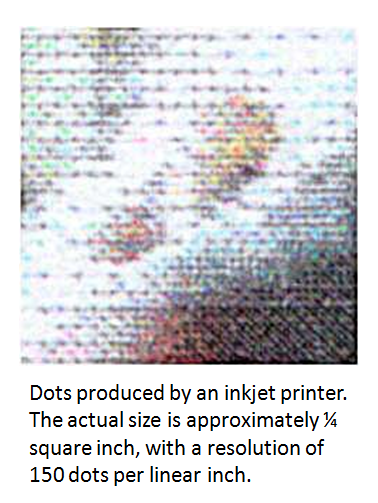

The biggest limitation of early laser printers was color, or rather, lack thereof. But again, help was waiting in the wings in the form of the ink jet printer. Like dot matrix printers, ink jet printers approximate characters with dots. But the dots aren't hammered onto the page, they're sprayed. Even inexpensive ink jet printers have hundreds of miniscule nozzles, so the print quality is extremely good. When it comes to rendering figures, both laser and ink jet printers are worlds beyond their ruffian forebears.

[Ink Jet audio]

The typewriter has come and gone, and with it the printing paradigm it provided. Is there a new paradigm on the horizon, one that will revolutionize the world of printing as never before? Actually, yes: the paperless office.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Notes and references:

M. Gladwell. Creation Myth. Xerox PARC, Apple, and the Truth About Innovation. The New Yorker, May 16, 2011. See also: http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2011/05/16/110516fa_fact_gladwell. Accessed April 24, 2012.

How Inkjet Printers Work. From the Howstuffworks website: http://computer.howstuffworks.com/inkjet-printer1.htm. Accessed April 24, 2012.

All pictures are from Wikimedia Commons.

This episode was first aired on April 26, 2012