Killer-App

by Andrew Boyd

Today, column D, row 3. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The first personal computers were embraced by hobbyists but not the masses. To reach a broader audience, PCs had to do something; something people would be willing to spend thousands of dollars for. What the industry needed was its first killer-app.

That app was introduced to the world in 1979 at the National Computer Conference by Bob Frankston. Frankston was an MIT graduate who'd hooked up with Harvard MBA Dan Bricklin. Bricklin had developed a program to help solve a homework problem. He thought it had potential, and got in touch with Frankston to help him refine it.

The reception to Frankston's presentation wasn't as enthusiastic as the two men hoped. As Bricklin later recalled, there were "twenty friends and family and two 'real' attendees." But the duo had built a better mousetrap, and the world was about to beat a path to their door. A highly regarded analyst at Morgan Stanley realized the software's potential. "hardware developments have always outpaced software," he observed. "for the [business] professional, there is precious little software available that is practical, useful, universal, and reliable." But he believed Bricklin and Franklin's creation, known as VisiCalc, was about to change all that. 'VisiCalc,' the analyst concluded, 'could some day become the software tail that wags (and sells) the personal computer dog.'

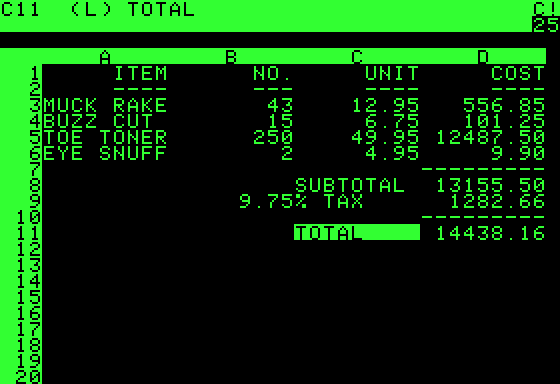

VisiCalc was a spreadsheet — a class of software that would forever simplify the lives of bookkeepers. That alone was breakthrough enough. But what ultimately grabbed people's attention was the radically new interface. Instead of typing commands on a command line — the model for virtually all software at the time — users could position the cursor with the arrow keys and type at different locations on the screen. Bear in mind that the first Macintosh, with its breakthrough mouse and graphical user interface, was still fifteen years away.

VisiCalc quickly caught on, selling hundreds of thousands of copies. But a host of competitors soon entered the market. The big upset came with the introduction of Lotus Development Corporation's 1-2-3. VisiCalc's success had been tied to the Apple II. Steve Wozniac, co-founder of Apple, once stated that two things were responsible for Apple's early success: Apple's floppy disk, and VisiCalc. The VisiCalc tail really did wag Apple's dog.

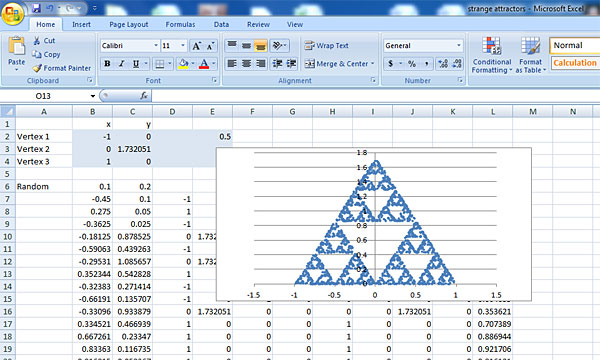

Unlike VisiCalc, 1-2-3 tied its fortunes to the soon to be dominant IBM PC. After a mere six years in existence, what was left of VisiCalc was purchased by Lotus. Lotus maintained a stranglehold on the spreadsheet market for over a decade. But it was slowly displaced by a spreadsheet that came bundled with Microsoft's Windows operating system. It's name? Excel.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Notes and references:

D. Bricklin. Software Arts and VisiCalc. From Dan Bricklin's website: http://www.bricklin.com/history/sai.htm. Accessed April 3, 2012.

R. Rumelt. VisiCorp: 1978-1984 (Revised). Case Study POL-2003-08, the Anderson School of Business, UCLA.

VisiCalc. From the Wikipedia website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VisiCalc. Accessed April 3, 2012.

The VisiCalc picture is from Wikimedia Commons. The picture of Excel is by E. A. Boyd.

This episode was first aired on April 5, 2012