No Math

by Andrew Boyd

Today, doing away with math. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Mathematics is at the forefront of the debate on education these days.  It's vital for work in science, engineering, and technology. And it's generally agreed that if the U.S. is to remain competitive, we need to improve our students' math skills. But that wasn't always the sentiment. In fact, at one time leading educators actually sought to discourage the teaching of mathematics.

It's vital for work in science, engineering, and technology. And it's generally agreed that if the U.S. is to remain competitive, we need to improve our students' math skills. But that wasn't always the sentiment. In fact, at one time leading educators actually sought to discourage the teaching of mathematics.

Helping lead the anti-math movement of the early twentieth century was William Heard Kilpatrick of the prestigious Columbia Teachers College. Kilpatrick regarded mathematics as "harmful rather than helpful to the kind of thinking necessary for ordinary living." "In the past," he said, "we have taught algebra and geometry to too many, not too few."

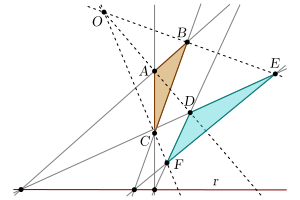

Kilpatrick expressed a view held by many in the early progressive education movement. The movement sought to replace rote learning with doing. The teacher's role wasn't to lecture, it was to facilitate: to get students involved in activities where they'd discover things on their own. 'We teach children, not subject matter' became a war cry of progressive educators. Much of the math being taught just didn't fit the mold.

But there was another reason math took a drubbing. To progressive educators, math classes not only failed to promote discovery, they didn't even teach useful skills. As one of Kilpatrick's colleagues put it, "Algebra is a nonfunctional and nearly valueless subject for over ninety percent of all boys and ninety-nine percent of all girls.''

As the progressive education movement grew, its impacts were starkly felt. In 1910, almost sixty percent of high school students took algebra. Half a century later, the number hovered below twenty-five percent. The situation was worse for geometry, dropping from thirty percent to just above ten. Mathematics was in freefall.

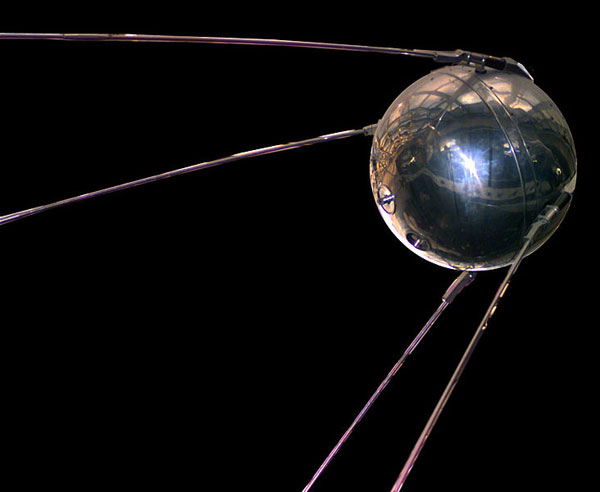

Then, in 1957, something happened that changed the course of American mathematics education: the launch of the Russian satellite Sputnik. Within a year, Congress had passed the National Defense Education Act, which appropriated money for math and science education at all levels.

Math has since made a comeback. An increasingly technological world has demanded it. But the debate raised by the progressive education movement remains. At issue are questions of what math to teach and how to teach it. Should students be required to take geometry, or would statistics be more valuable? Should they dryly learn the rules of algebra, or discover the need for algebra from everyday problems? Thankfully, the questions really aren't all black and white, nor are the answers. But finding exactly the right shade of grey is a challenge.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Notes and references:

W. Hayes. The Progressive Education Movement: Is It Still a Factor in Today's Schools? R&L Education, 2006.

D. Klein. A Brief History of American K-12 Education in the United States. In Mathematical Cognition, J. Royer, ed. Information Age Publishing, 2003. See also http://www.csun.edu/~vcmth00m/AHistory.html. Accessed December 6, 2011.

The picture of William Heard Kilpatrick is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. The algebra picture is from a U.S. government Web site. The geometry and Sputnik pictures are from Wikimedia Commons.

This episode was first aired on December 15, 2011