Land Grant Colleges

by Andrew Boyd

Today, college for all. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Early in U.S. history college education was largely a religious affair. Religious groups needed trained ministers, so they opened colleges. Given the lack of universal public education, these colleges became learning centers — at least for those who could afford them. College, it seemed, was only for the well-to-do.

By the mid eighteen hundreds, Congress was concerned about this state of affairs. Were the educational needs of U.S. citizens being met? The nation's founders had articulated the importance of education as early as the Second Continental Congress. 'Religion, morality, and knowledge,' they wrote in 1787, 'being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall be forever encouraged.'

Three quarters of a century later, Congress asked if it was providing sufficient encouragement.

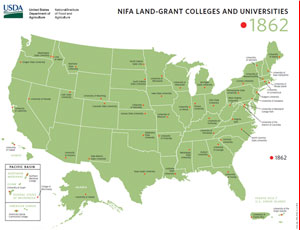

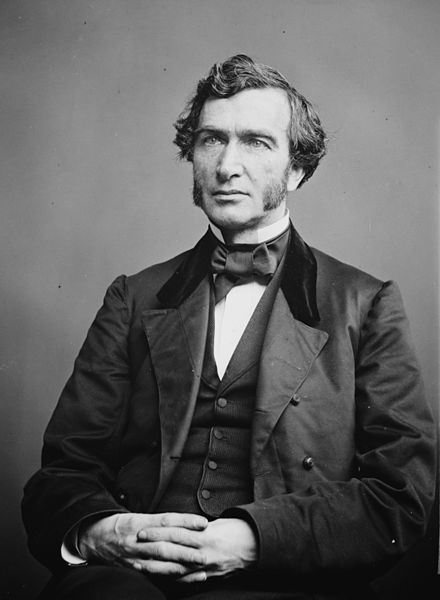

Enter house representative Justin Smith Morrill and the first Morrill Land Grant Act. The idea was for the U.S. government to give land to each state, land that in turn could be sold and used to finance higher education. It was signed into law by Abraham Lincoln in 1862.

The act is two handwritten pages in length and calls for establishing "at least one college where the leading object shall be 'to teach' agriculture and the mechanic arts" But while congress wanted a practical education, education wasn't to be limited to the practical. As stated in the act, college curricula were to be designed "without excluding other scientific and classical studies in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes." The term "industrial classes" isn't one we'd use today, but the point's clear. Land grant colleges were intended for everyone.

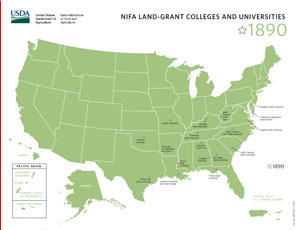

Later, in 1890, Congress realized that initial goal wasn't being met. Some colleges were excluding blacks. The second Morrill Act required land grant colleges to drop race from their admission policies or to establish separate, properly funded colleges for blacks. (Bear in mind that desegregation in the U.S. was still more than a half century away.)

The two Morrill Acts launched almost eighty universities, including Cornell, Ohio State, Texas A&M, and the University of California system. But the acts also helped spur the growth of other great public universities; schools like Georgia Tech, the University of Texas, and the University of Washington, all of which opened their doors in the wake of the first Morrill Act.

|

Few pieces of legislation have had such far-reaching effects on education as the Morrill Acts. They paved the way for the U.S. to build one of history's great systems of higher education; a system widely available to people from every background.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Notes and references:

M. Katz. 'The Role of American Colleges in the Nineteenth Century,' History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 2 (Summer, 1983), pp. 215-223.

The Morrill Act (1862). From the U.S. government Website: http://ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=33. Accessed October 11, 2011.

The Morrill Land-Grant Acts. From the Wikipedia Website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morrill_Land-Grant_Acts. Accessed October 11, 2011.

The Northwest Ordinance (1787). From the U.S. government Website: http://ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=8. Accessed October 11, 2011.

The picture of Justin Smith Morrill is from Wikimedia Commons. All remaining pictures are from state or U.S. government Websites.

This episode was first aired on October 12, 2011.