The Atocha Bombing Memorial

Today, mourning and monuments. The Honors College at the University of Houston presents this program about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

September 11, 2001 is a date seared into the American mind. In Spain, they have a similar date: March 11, 2004. A series of coordinated bombings occurred in Madrid, killing 191 people and wounding over 1,800. As on 9-11, the attack was horrifically well thought out. It happened 911 days after the 9-11 attack in New York City, and three days before the general elections in Spain. 10 bombs exploded on four different commuter trains right at the peak of the morning rush hour.

Such attacks are designed to rip into the public space and shake the collective mind to its core. As a consequence, we face a peculiar problem in trying to commemorate the victims of such terrorism. On the one hand, we want to make certain the victims are never forgotten. We want their names to be known, and their total innocence proclaimed. But on the other hand, we also want to defy the people behind the attack. To commemorate a great loss in this instance is to cede to the attackers a measure of their success. We want the monument to give the victims back their humanity, to console the rest of us, and to show our enemies they failed to break us. And that's a tall order.

The American response to 9-11 was to create a private/public partnership to fund a vast project. It will be both a national memorial and a museum. Not only is it on the very site of the attack; it will house some of the victims' remains. The 9-11 Memorial has been a daunting, complex and controversial project, and is scheduled to open on September 11th, 2011: a full decade after the event.

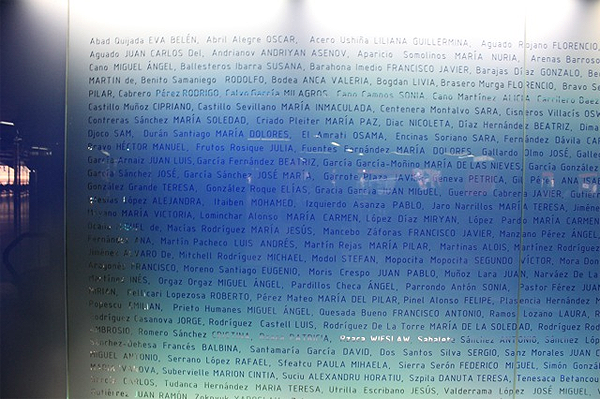

In contrast, the Spanish government completed their memorial in just three years. The Madrid attack is known by the designation 11-M, for March 11; so the monument takes the form of a cylinder of clear glass bricks exactly 11 meters high. It sticks out above street level in front of the Atocha train station, which was the destination for the trains that were bombed. Below the monument there is an empty blue chamber. It is filled with natural light streaming in from the glass cylinder above; this is its only light source. The chamber is sealed, because it's under pressure, which gives you an odd feeling of stillness as you enter. The pressure inflates a massive plastic film that rises up into the glass brick tower, all the way to the top.

The film itself is inscribed with thousands of words in numerous languages. These words are not from anyone famous. They are anonymous messages from around the world sent immediately after the bombings. In different tongues, including Arabic, we read the anguish, shock, anger, and defiance of normal people, expressed in everyday words. 'Something of us left with you; we'll never forget you.' 'The world must change.' 'How is this possible?' 'No to terrorism.' And at the very top of this giant bubble, we read: 'It takes a lot of imagination to deal with reality.'

The Madrid monument is a surprising combination of geometric abstraction and naked human emotion. Its pressurized balloon rising within a glass column somehow captures the contradictory emotions surrounding the event: emptiness, outrage, clarity, and that most fragile of human virtues: hope.

I'm Richard Armstrong, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Sources:

For the New York 9-11 Memorial, see the official (and very informative) website, which contains animated renderings of the monument: http://www.911memorial.org/.

For the Atocha memorial, see the design firm's web site which includes several photographs of its installation (site is in Spanish with some poor English translation; scroll right for more photos): http://www.estudiosic.es/index.php?/proyectos/monumento-a-las-victimas-del-11m/.

All images are of the Atocha Bombing Memorial, Madrid, Spain. Photos by Richard Armstrong.