Let's Be Pedants

Today, let's be pedants. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Take a word -- say, elastic: As a pedantic engineer I'll tell you that an elastic material deforms in direct proportion to the load we put on it. Release the load and it exactly reverses that deformation. So, even though glass is half as stiff as steel, it is elastic, while soft rubber turns out to be inelastic. Rubber deforms one way as we load it, and another way as we unload it.

Yet, by a second definition of the word, rubber is elastic. That definition merely says that an elastic material comes back to its original state when we unload it. Rubber does do that much.

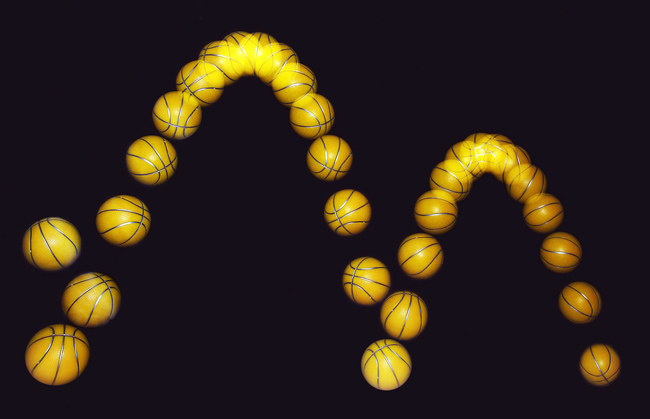

Sequence of photos of a basketball reveal that it loses energy on each bounce. Its "coefficient of restitution" is less than one, and there is hysteresis as it is stressed and released. It is not elastic by the first definition in the text. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In still another use of the word, to be elastic, something need only recover -- like, say, hurt feelings. So many related meanings, and those meanings can be contradictory!

Not all multiple meanings are that tricky. Mischief arises when meanings lie close to each other. Context keeps us from confusing a golf club with the club house. We become muddled when, say, we throw about the many-hued word love -- or the technical word, efficiency. Engineers will quote many different automobile efficiencies -- each important, no two the same.

Or take the word pedant: Is a pedant someone who's, ipso facto, boring? Or is it someone who wants to get things right? Our language has another word, not much used, that carries less baggage. That word is precisionist -- someone who simply works at being precise -- like an orchestra violinist or a brain surgeon. That's pedantry that we should all keep in the back of our minds as we write or speak.

Definitions are often the enemy of precision because they're all circular. We define every word with other words that have to be defined by more words still. Caught in that great looping circular trap, we gain a precise understanding only when we visualize the truth of a thing beyond the words we use to describe it.

Example: to bring out the inner pedant in a scientist, just ask the difference betweencentrifugal and centripetal forces. When we swing a rock on the end of a rope it takes a force to keep bending the rock's path to a circle. Cut the rope and the rock flies off on a tangent. One of those words (don't ask me which) describes the force on the hand holding the rope; the other, the force acting on the rock. That's silly! All forces act in both directions. Should I give one name to the force of my feet the floor and another to the force of the floor on my feet? I don't see the sense of that.

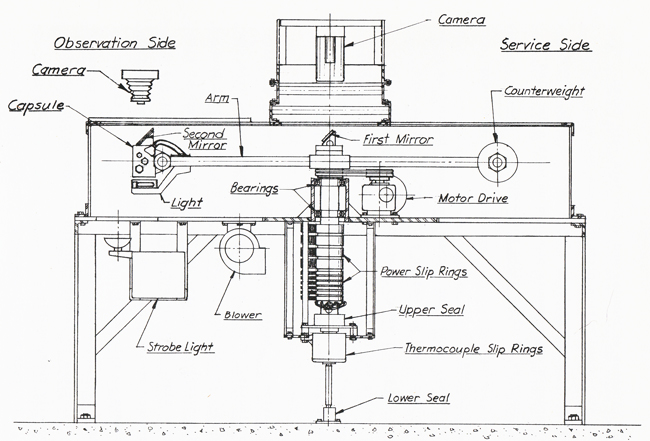

Centrifuge developed for NASA by J. Lienhard for observing boiling at various gravity levels. The centripital/centrifugal forces in the test capsule created elevated gravity within it. Click on the image to see it at high resolution.

Leonardo da Vinci once said:

If you wish to demonstrate in words ... do not meddle with things appertaining to the eyes by making them enter through the ears, for you will be far surpassed by the painter.

So we erect the word pedant as armor against that occasional person who needs to explain all reality in that single limited language of words. All of us, now and then, stumble into a verbal morass. That happens when we mistakenly tread on the turf of matters that should be left to an equation, a sonata, or a cartoon.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we are interested in the way inventive minds work.

My thanks to linguist Richard Armstrong and theoretical mechanic Lewis Wheeler for their counsel. For the Leonardo quotation, see: E. Belt, Leonardo the Anatomist. (New York: Greenwood Press, Pubs., 1969). (Original printing, Univ. of Kansas Press, 1955.) See Episode 2017 for more on the very peculiar "elastic" characteristics of rubber.

I allude to stress/strain hysteresis in rubber at the beginning of this episode. For more on that topic, see the section on elastic hysteresis in the Wikipedia article on Hysteresis.

For more on the centrifuge experiment pictured above see this NASA CR-1551 Report.

I've probably awakened the inner pedant in many listeners with my dismissal of centripetal and centrifugal. Googling these words, we find talk of a reactive centrifugal force -- the force "paired" with a centripetal force. The plot thickens when one speaks of a force associated with a Coriolis acceleration -- debate goes on whether that can be called a real force. Perhaps such distinctions have merit, but my point is that if merit exists, it will not be captured in words alone. (Many such issues torment physicists. I am reminded of Steven Hawkings famous statement, "When I hear about Schroedinger's cat, I reach for my gun.")