Storing Energy for the Power Grid

by Andrew Boyd

Today, power. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The power grid. It sounds a bit ominous. What exactly is it?

The electricity for our TVs and toaster ovens arrives through an outlet in the wall. But it begins by passing through a vast, interconnected collection of wires that make up the so-called power grid. At the end of some wires, like our wall outlets, electricity is taken out of the grid. And at the end of other wires, like power plants, we find electricity coming into the grid. It's like a vast tank of water, where at any moment thousands of people are pouring water in and thousands are taking water out. But there's one big difference.

A water tank can inexpensively gather water on a rainy day and save it for a sunny day. That's not so easy for the power grid. Storing electrical energy on a large scale can be expensive and inefficient. So for the most part, we haven't used storage. When we need more electricity, we simply generate more.

The price we pay is having to build enough power plant capacity to handle peak demand. That means our power plants spend much of their time sitting idle. We could build fewer plants if we could create energy when there's low demand and store it for periods of high demand.

So engineers have a renewed interest in ways to store electrical energy. Many ideas have been around for years. Others are new. All are creative. Flywheels are one idea. An electrical motor sets a large mounted wheel spinning. When needed, the motion of the wheel is converted back into electricity.

Of course, there are batteries galore. Batteries convert electrical energy to chemical energy then back to electrical energy when needed. Batteries aren't usually a good choice for storing large amounts of electrical energy — they're just not economical.

But here's a nifty idea. It's called vehicle to grid technology, and here's how it works. Whenever an electric car is plugged in, its battery is hooked into the power grid. Now, we normally think of these batteries as simply drawing power from the grid. But what if they actually fed electricity back into the grid? You arrive home from work and find your car battery still has charge left. Electricity's in high demand after work, so you release your battery's energy back into the grid. Later that night, when everyone's asleep, your car recharges itself. Of course, your electricity provider gives you a rebate on your bill. After all, you stored power for the grid and saved the provider money.

It's hard to say how our interaction with the grid will change in coming years. But change is coming. And the wealth of ideas is both amazing and inspiring.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Notes and references:

Energy Storage. From the Wikipedia Website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_storage#cite_note-23. Accessed May 10, 2011.

Vehicle-to-Grid. From the Wikipedia Website: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vehicle-to-grid. Accessed May 10, 2011.

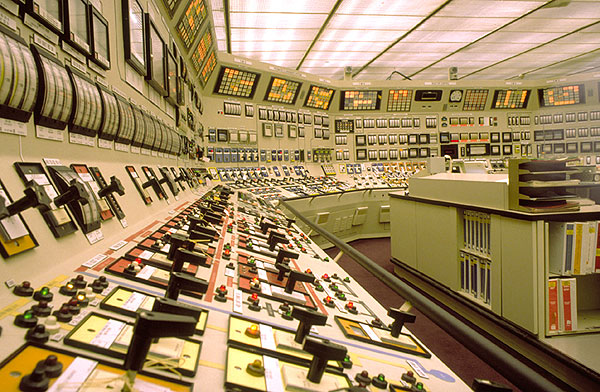

The picture of the Prius plug-in is from a Toyota Website. All other pictures are from U. S. government Websites.