Muscle Memory

Today, muscle memory and engineering design. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I think a lot about muscle memory as I grow older -- our wonderful ability to do complex tasks unconsciously -- the fine motions of bike riding, piano playing, shaving, of walking. Debate goes on over just how the brain does that. So I won't go there. Rather, let's think about muscle memory and engineering design.

Take typing. We're stuck with our QWERTY keyboard layout because it was designed before people realized they could touch type. So we type on QWERTY keyboards without looking. Our brain says G and our finger unconsciously goes to that key. Our muscle memory is wed to QWERTY; and now we won't accept a better layout.

Or think about muscle memory and perfect pitch. The rare person who has it can sing, say, an E-flat with no context. Here in America just a few out of every ten thousand people have perfect pitch. (In China, with its pitch-inflected language, the number is higher. Chinese children are attuned to pitches from the cradle.)

But ask an average citizen on the street to sing the first line of some popular tune. More often than not, she'll do it in the key she's been singing along with her radio. That's not perfect pitch, it's vocal cord muscle memory.

Singing from printed music is a lot like typing. The muscles that tense our vocal cords react to a written E-flat much as our typing finger reacts when our brain says the letter E. So what happens if we're asked to sing a piece in a key other than the one where it's written? Now that E-flat has to be sung as, say, a G.

Without perfect pitch, we don't know that we're being started out in the wrong place. But think about typing. We've all had the experience of trying to type on an unfamiliar QWERTY keyboard. Our touch-typing deteriorates. Same thing with singers: Each time we try to sound a note, our muscles are doing something inconsistent with our muscle memory of that printed note.

I meet people who think they can play a hymn in a key other than the one it's written in. Of course the result is the same as giving a typist a strange keyboard. Things go wrong. Notes come out flat or sharp -- like the typist reaching for W and typing E.

This is an ongoing problem in engineering design. Any machine -- automobile, cell phone, piano -- has to interface with a human being. And we engineers are constantly tempted to decide what should work when we create something new. The result might be a highway with an awkward intersection. Or a copy machine with an array of buttons that give it vast, but incomprehensible, flexibility. Which of us has not been flummoxed by a new point-and-shoot camera with too many obscure switches in illogical places?

It's a hard-learned lesson in humility. But, if we try to design without keeping our users' muscle memory clearly in mind, the result will be ... Well, the machine we build will simply be out of tune.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

See the Wikipedia article on Muscle Memory.

For another slang on this subject see Episode 730.

Terms other than perfect pitch usually refer to tone recognition that less than perfect -- absolute pitch or relative pitch. These are sometimes used to designate a highly honed muscle memory of pitch.

Another factor in all this is the actual value of a given A above Middle C -- whether it's really 440 Hertz or some other value. For more on that matter, see Episode 1305. Baroque music will often be played at A as low as 415, which can further stress a singer.

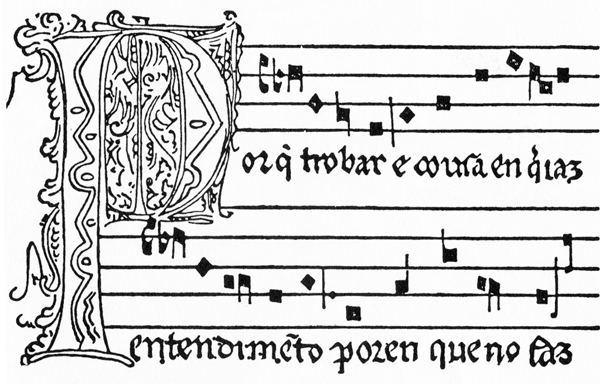

Photos by J. Lienhard. Plainchant sample is clipart.

Notes from a time when A was not defined and singers simply agreed upon their mutual muscular memory.