American Women's Suffrage and Alice Paul

by Andrew Boyd

Today, we march. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

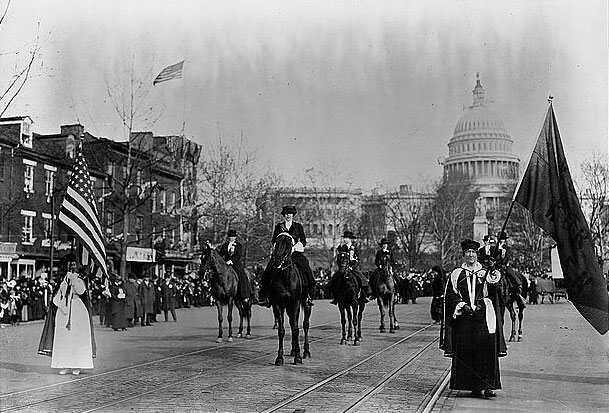

The year was 1913. Some eight-thousand well dressed demonstrators prepared to march down Pennsylvania Avenue. It was the day before President Woodrow Wilson's inauguration, and Washington was filled with politicians and political power brokers. The day began uneventfully. But the volatile issue behind the parade proved too much. Spectators "taunted, spat upon, and roughed up" the marchers, while police did little to control the crowds. A mounted cavalry unit was called in by the War Department to restore order.

The demonstrators were women. Their goal: a constitutional amendment giving women the right to vote. It was a pivotal moment in the women's suffrage movement. The movement had been alive for almost seventy-five years, pre-dating the Civil War. But for the many years of effort, it had reached a standstill. Influential leaders like Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Stanton, and Susan Anthony had passed away at the turn of the century. By the time of the march, the National American Woman Suffrage Association lacked the fervor that had once been its trademark.

Enter Alice Paul. A graduate of Swarthmore who later earned a doctorate at the University of Pennsylvania, Paul had recently returned to the United States from England, where she'd experienced suffrage activism first hand. She convinced the American suffrage association to allow her to form a Washington political lobby — a lobby that was given the Association's blessing and a budget of thirteen dollars.

The Washington parade thrust the sleepy women's suffrage movement onto the front page of newspapers. And that was just the beginning. Lobbying and political theatre were relentless in the years that followed. Paul and her supporters were the first group to ever picket the White House. Hundreds of women were arrested and jailed on charges of "obstructing sidewalk traffic." Their imprisonment and shameful treatment while in jail proved an important catalyst for public opinion.

Seven years after the march on Washington, the nineteenth amendment was ratified, which in its entirety reads: "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex." The amendment came exactly fifty years after the fifteenth amendment, which states that no citizen of the United States can be denied the right to vote on account of race or color.

The women's suffrage movement was about the right to vote, but it was also about something even more basic: the right for women and men to be treated as intellectual equals. It's something we take for granted today, but it was a long and difficult road engineered by a most dedicated group of citizens.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Notes and references:

Many thanks to Beverly Ladnier for bringing this topic to my attention.

Special thanks to Professor Landon Storrs of the University of Houston Department of History for help in preparing this episode. As Dr. Storrs points out, while Alice Paul and her followers were important catalysts for change, it would be incorrect to suggest they were solely responsible for women's suffrage. Paul broke with the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) over tactics years before the nineteenth amendment was ratified. And while NAWSA was less radical than Paul's followers, they also did much of the often thankless work needed to push through ratification.

C. O'Hare. Jailed for Freedom: American Women Win the Vote. Troutdale, Oregon: NewSage Press, 1995. Edited from the original version Jailed for Freedom, by D. Stevens, 1920.

One Woman, One Vote. M. Wheeler, ed. Troutdale, Oregon: NewSage Press, 1995.

All pictures are available to the public as their copyrights have expired.