Garden City Utopia

Today, a Garden City Utopia. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The 19th century was an era of Utopias. So many people set out to build perfect worlds apart -- Shakers, Icarians, New Harmony. Most failed. A few, like the Amish and Mennonites, live on in an uneasy peace with reality.

One person thought things out more completely than most. Ebenezer Howard was born, middle-class, in London in 1850. He was schooled to the age of fifteen and self-taught after that. At 21, he went to America. He tried homesteading in Nebraska. That failed, so he went to Chicago -- a city now rebuilding after its devastating fire.

One person thought things out more completely than most. Ebenezer Howard was born, middle-class, in London in 1850. He was schooled to the age of fifteen and self-taught after that. At 21, he went to America. He tried homesteading in Nebraska. That failed, so he went to Chicago -- a city now rebuilding after its devastating fire.

He worked as a stenographer as he watched the city's planned rebuilding -- the interweaving of homes, businesses and parks. He heard talk about the Garden City.

That term lingered after he went back to England. He was now a business stenography expert. Parliament's stenographic service hired him. He married, had children, invented. He almost sold his variable spacing mechanism for typewriters to Remington, but their offer was too low. Later, he invented a shorthand typewriter.

He also read about social reform and ran with the radical reformers of his time. Then he found Edward Bellamy's 1889 book, Looking Backward. It's about man who somehow awakens in the year 2000 to find America is one great planned community based on service to that community. Howard resolved that he would build model cities that would provide a good life for all.

Howard became one of the most prominent among the many voices calling for such cities in the late 19th century. He began promoting his own design in a book that took many forms and titles. The final title used Chicago's motto. It was The Garden City of To-morrow. He formed a Garden City Association. They bought up real estate and set out to build such cities.

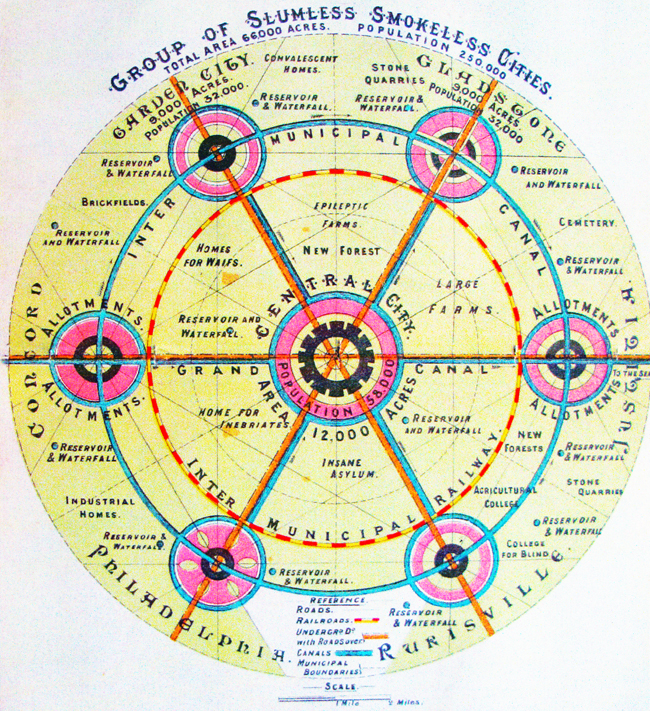

His model city, like so many others, had fractal geometric perfection. A central city is surrounded by farms, reservoirs, and parks. Six more cities form a perfect hexagon around that belt. And they're connected by a concentric circular railway and canal.

This slumless, smokeless world had an almost eugenic dark side. Scattered through the Arcadian inner green region were an insane asylum, a home for inebriates, and an epileptic farm. Still, people listened to Howard. He was even knighted for his efforts.

Among his investors: George Bernard Shaw! And Shaw made money chiding himselfwhen he wrote that Howard was:

... one of those heroic simpletons who do big things whilst our prominent worldings are explaining why they are Utopian and impossible. And of course it is they who will make money out of his work.

So let's not laugh too loudly at Howard. We too want our communities to reach that slumless, crimeless, greedless perfection. But we might make headway where he failed; because we know that our good city will emerge as we build it patiently, one brick a time.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

R. Beevers, The Garden City Utopia: A critical Biography of Ebenezer Howard. (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1988). My thanks to Pat Bozeman, UH Libraries, for calling my attention to this source.

M. Miller, Howard, Sir Ebenezer (1850-1928), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. ?, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004): pp. 330-333.

E. Howard, To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Reform. (London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co. Ltd., 1898). (A fully developed edition of Howard's book before it took its final title)

See also the Wikipedia articles on Ebenezer Howard and Edward Belamy

For more on Utopian cities see Episodes 738, 2261, and 2641.

Images: E. Howard photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons; ideal city layout from Howard's book; rainbow over Houston photo by J. Lienhard.

Our perfect, unplanned, city of Houston, TX