King Camp Gillete

Today, the razor blade king tries to reform society. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In 1895 King Camp Gillette was the salesman for the man who invented cork-lined bottle caps. "Invent something people use and throw away," the man told him. It'd sure worked for him.

Gillette wondered what he might invent. It hit him one morning while he was shaving. He thought up the safety razor, but he couldn't figure how to make good disposable blades. For years he struggled. Finally he met William Nickerson.

Nickerson was a fine inventor. This was a fine challenge. Nickerson finally saw that he could make the blade wide. He could let the holder bend it into position. Then he'd have both accuracy and a sharp edge. Together, Gillette and Nickerson began making safety razors in 1903.

The next question was what to name the thing. If they called a razor blade a Nickerson, that was too suggestive of nicked skin. In the end Gillette's name attached to the invention, and his face rode on the razor blade wrapper. Within a few years Gillette was a millionaire.

Now that's only the first half of Gillette's story. Howard Mansfield tells the rest, and it gets very interesting. The year before he cooked up the safety razor, Gillette published a book on another idea entirely. It was terrifying and idealistic.

His Utopian socialistic world would be based on universal cooperation. All production would be done efficiently by one great company with all people as shareholders. "Selfishness would be unknown, and war would be a barbarism of the past," he wrote.

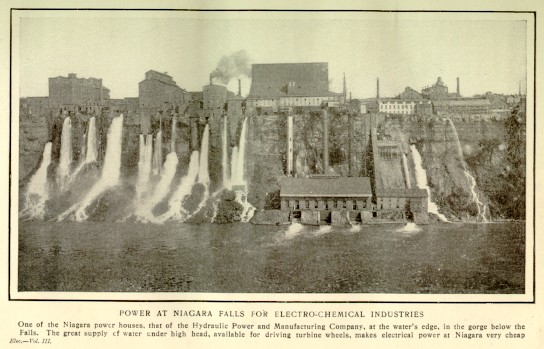

He imagined all 60 million Americans living in one great Metropolis. It'd be powered by the Niagara River. It'd have a hundred million rooms and be served by vast common dining halls.

Before WW-I he tried to set up his World Corporation -- this time in the Arizona Territory. He asked Teddy Roosevelt to be its president. When that failed, he turned to social reformer and writer Upton Sinclair. Sinclair arranged a disastrous meeting between Gillette and Henry Ford. The two millionaires talked past each other. Finally, they simply shouted in anger.

Sinclair also helped Gillette with his most cogent statement -- a book called The People's Corporation. Even that was naive at best. Stuart Chase said that his sincerity was deep and compelling. "... but his solution is quite untouched by the realities which guard the road to Utopia."

In his last years Gillette tried to extract oil from shale. He still had his inventive verve. But he carried his socialism to the grave. He didn't see that the simple elegance of his safety razor was no match for the complexity of human affairs.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Mansfield, J., The Razor King. American Heritage of Invention and Technology, Spring 1992, pp. 40-46.

Gillette, K.C., The Human Drift. Boston: New Era Publishing Co., 1894. (This was the first of several books in which Gillette set down his ideas. The dedication reads: "The thoughts herein contained are dedicated to all mankind; for to all the hope of escape from an environment of injustice, poverty, and crime, is equally desirable.")

Gillette, K.C., The People's Corporation. New York: Boni and Liveright Publishers, 1924. (This was Gillette's last book, 30 years after the first. Now the dedication says simply: "To MANKIND.")

mid-20th century Gillette blade provided by St. John Antiques, Galveston

From Electricity in Everyday Life, 1904.

The Niagara Falls powerhouse in 1904. This is what Gillette had in mind as the powerhouse for his Utopian community.