Reinventing Foundation

Today, we reinvent foundations. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

So: How much do buildings weigh? A typical house might weigh 70 tons and stand 25 feet high. The Empire State Building is 50 times higher so it should weigh 50 times as much -- around 3500 tons, right? Wrong. It weighs 350 thousand tons!

We missed by a factor of a hundred because weight should increase roughly as the cube of height -- as long as the shape is the same. Skyscrapers are slenderer than houses, so it's not quite that extreme; but weight still goes up very strongly with height.

Skyscrapers began sprouting in Chicago and New York in the 1890s. By 1909 Century Magazine carried an article titled "Foundations of Lofty Buildings". Century tended to be a literary magazine. But this technical article runs eleven two-column pages with detailed drawings. Foundations were becoming a major worry.

The oldest of the skyscrapers that stand out on today's New York skyline is the Woolworth Building. It's just under 800 feet. Cass Gilbert hadn't yet been hired to design it when this article appeared. It talks about buildings only half that high.

The article explains how New York real estate has grown so absurdly expensive that building will not be deterred by foundation costs. Construction will go on despite the fact that most Manhattan soil is sand. So how do we build skyscrapers on sand?

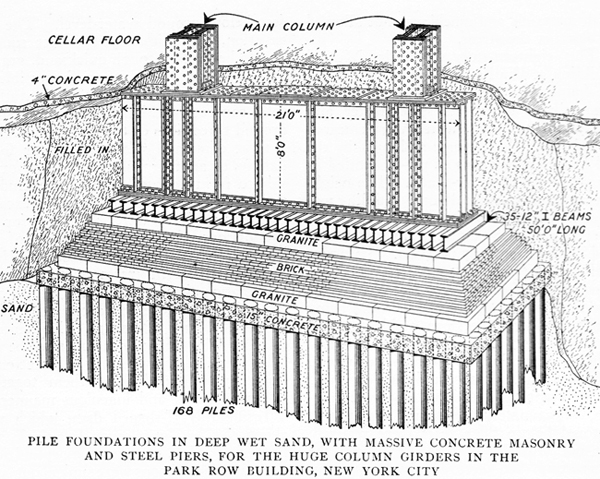

We dig far enough down to reach either bedrock or hard wet sand. Steel columns can be driven down to bedrock. Or a pyramidal structure can be spread out below the building to distribute its weight on hard sand far underground.

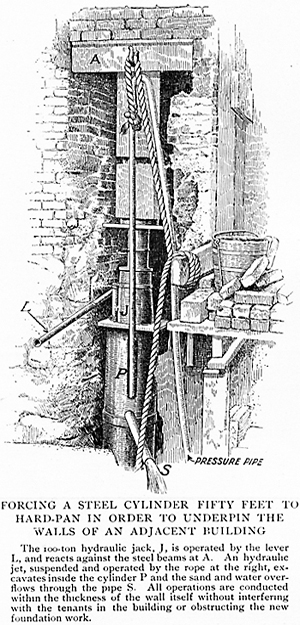

A builder who undermines the foundation of a smaller building next door is in for big legal trouble. So we see strategies for digging foundations right up against a neighbor's underground wall. The buildings rise upon some very narrow strips of land.

A builder who undermines the foundation of a smaller building next door is in for big legal trouble. So we see strategies for digging foundations right up against a neighbor's underground wall. The buildings rise upon some very narrow strips of land.

In the century that followed, buildings rose from the 400-foot height of the larger ones in the article to the new half-mile-high Burj Khalifa skyscraper in Dubai. But weight has not gone up as rapidly as we'd expect. Construction is more weight-conscious.

The Burj Khalifa is twice the height of the Empire State Building, but less than twice its weight. (Its foundation still reaches down 160 feet into the soft soil below it.) It's five times the height of the Great Pyramid, yet only a sixth the weight of the Pyramid. Another comparison, by the way: The largest super tankers are just a bit shorter, and they weigh about the same, as the biggest skyscrapers.

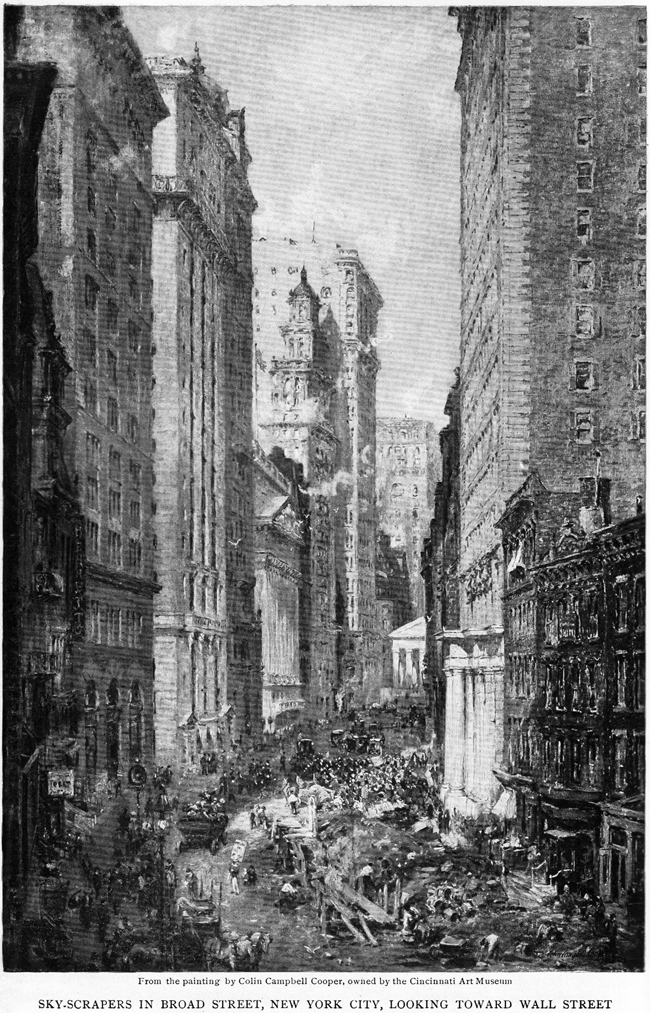

In any case, my magazine illustrations revel in massiveness. An artist shows Wall Street lined by twenty-story buildings with a clutter of horse-drawn vehicles on the crowded street below. It's a Hogarthian vision of where all this is going. Well, New York continued its upward reach; but it's pretty well cleaned up the streets below. And we can only wonder at the millions of tons of iron now woven, out of sight, in the ground below it.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

F. W. Skinner, Foundations of Lofty Buildings. The Century Magazine, Vol. LXXVII, (New series Vol. LV) No. 4, March, 1909, pp. 771-781. All images are from this source.

See the Wikipedia article on the Burj-Khalifa tower.

Colin Campbell Cooper painting, titled Broad Street Canyon