Milton Bradley

by Andrew Boyd

Today, a game maker. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The games Candy Land, Chutes and Ladders, Mouse Trap, and Cootie have twice been a big part of my life; once as a child, then again as a parent. And they all come from a company started by Milton Bradley.

Bradley didn't set out to be a game maker. He trained as a draftsman, drawing plans for railroad cars, then went on to open a lithography business in 1860. His most famous lithograph was of a young presidential candidate named Abraham Lincoln. It was a best seller — until Lincoln decided to grow a beard.

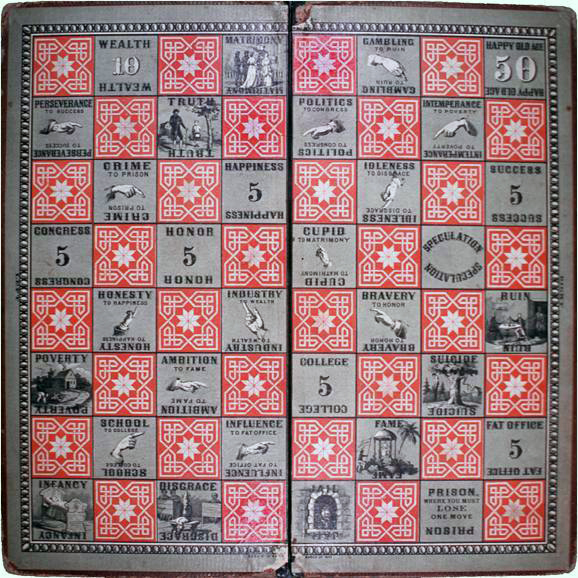

Bradley became a game maker fortuitously. Playing a board game with a friend, he had an idea for one of his own. In Bradley's game, players moved pieces on a converted checkerboard, with labels added to the squares. Landing on the square labeled "industry" transported a player to the square labeled "wealth". "Gambling" led to "ruin"; "intemperance" to "poverty." The game was called the "Checkered Game of Life."

The Checkered Game of Life

Bradley had no idea how popular the game would become. It was perfect for its era — pastime and Puritanical preparation rolled into one. Over the course of one winter, Bradley sold more than forty-thousand copies. He was convinced his future lay in games. Unfortunately, that spring marked the beginning of the Civil War. But while it was a tragedy for the country, it turned out to be a blessing for Bradley. Soldiers got bored. And a reasonably priced game kit was just what they needed. Charitable organizations bought and distributed kits made by Bradley. And his life as a game maker was sealed.

Bradley was more than just a successful entrepreneur. He was an early advocate of the emerging kindergarten movement started by Friedrich Fröbel in Germany. Fröbel used toys, called Fröbel's gifts, to spark the imagination of young children. Bradley embraced the idea, and supplied blossoming kindergartens with educational toys. For decades, this component of Bradley's business lost money. Yet he was so personally committed to the kindergarten movement he continued to produce educational toys even when it put his business at risk.

In a gratifying turn of events, Bradley's efforts were rewarded. As more and more teachers embraced creative play, they needed just what the Milton Bradley Company offered. Bradley lived long enough to see the coming changes, but died before the creative play movement fully matured. Sometimes that's just the way things happen when you play the game of life.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

[Audio: 1960s Game of Life television commercial]

For a related episode, see FRIEDRICH FROEBEL AND KINDERGARTEN.

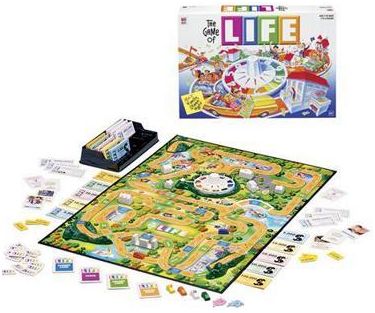

In 1960, one-hundred years after the game was first sold, the Milton Bradley Company released a new, quite different version of the Game of Life. Updated versions are still sold to this day. A video of the original 1960s television commercial can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LjMJ6bGXm38.

R. H. Miller. Milton Bradley. Part of the Inventors and Creators series. Florence, Kentucky: KidHaven Press, 2004.

The Milton Bradley Company. From the Funding Universe web site: http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/Milton-Bradley-Company-Company-History.htm. Accessed September 29, 2009.

Milton Bradley. From the Wikipedia web site: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milton_Bradley. Accessed September 29, 2009. The pictures of Milton Bradley and the Checkered Game of Life are from Wikimedia Commons. The recent picture of the Game of Life is taken from the Hasbro (Milton Bradley subsidiary) web site.