Scapa Flow

Today, Scapa Flow. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Scapa Flow is a sheltered bay nestled in the Orkney Islands just beyond the northernmost tip of Scotland. The Orkneys are flat, green, and quite beautiful. And yet, buoys with memorial plaques bob in Scapa Flow. So many ships have perished in these waters during the past century. It seems to make little sense.

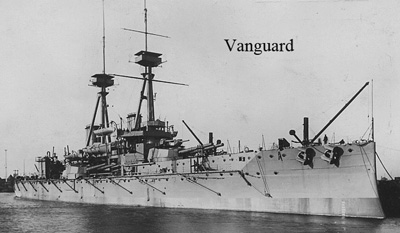

Well, there's plenty of illogic in the history of this peaceful place. The first loss was the WW-I British battleship HMS Vanguard, temporarily anchored in Scapa Flow. Its munitions somehow became overheated and exploded, killing all but two of her 845 men.

Well, there's plenty of illogic in the history of this peaceful place. The first loss was the WW-I British battleship HMS Vanguard, temporarily anchored in Scapa Flow. Its munitions somehow became overheated and exploded, killing all but two of her 845 men.

A second British battleship, the Royal Oak, anchored there just after WW-II began. A German U-boat made a daring raid into the very middle of this sheltered anchorage and found the Royal Oak on Friday the 13th, October, 1939. One torpedo from the first salvo hit the ship and did minimal damage. It wasn't clear to the crew what the muffled WHUMP! really meant. So the Germans had another twenty minutes to load a second salvo.

This time they scored three solid hits. In minutes the ship had capsized and sunk. It landed with its superstructure crushed on the bottom and the keel just thirty feet from the surface. Only a third of its crew -- chilled and oil-soaked -- got out alive. Eight hundred more sailors were now entombed below it.

This time they scored three solid hits. In minutes the ship had capsized and sunk. It landed with its superstructure crushed on the bottom and the keel just thirty feet from the surface. Only a third of its crew -- chilled and oil-soaked -- got out alive. Eight hundred more sailors were now entombed below it.

I was in fourth grade and this was frightening news. The gathering war clouds had darkened my childhood since the Japanese had invaded China. Now the pride of the British Fleet was sunk in its home waters. How long before I saw enemy submarines in the nearby Mississippi.

The Royal Oak was state-of-the-art naval weaponry when it was built in 1914. Its great 15-inch guns were then the largest ever put on a ship. It now bulged with protective siding to absorb torpedo impacts. But technology had moved too quickly, and that siding was too little to absorb the newer German torpedoes.

The Royal Oak was state-of-the-art naval weaponry when it was built in 1914. Its great 15-inch guns were then the largest ever put on a ship. It now bulged with protective siding to absorb torpedo impacts. But technology had moved too quickly, and that siding was too little to absorb the newer German torpedoes.

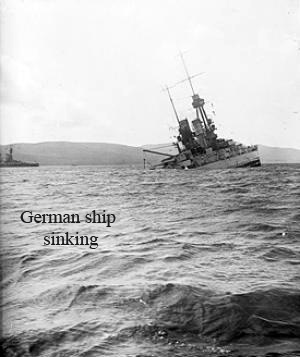

And there's still more in Scapa Flow. Between the Vanguard and Royal Oak, a whole fleet went to the bottom there. At the end of WW-I, the Allies herded the defeated German Navy into Scapa Flow. Then, without warning, German skeleton crews made a kamikaze decision. They scuttled 74 ships, 400,000 tons of shipping, before the Allies could react.

The surface of those waters was still being smoothed by slow unremitting oil leaks for over seventy years. And the well-built hull of the Royal Oak still held air pockets that its drowning sailors never reached. In the end, we saw no German submarines in the Mississippi River. Those British sailors beneath the bucolic surface joined the millions who died to prevent that.

Grass grows over the horrors of war. Waters close upon them. It's a stretch to imagine the vast phantom navy below the calm beauty of this quiet place. Our eye is drawn instead to terns, osprey, and avocets -- that were there first and will be long after.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

K. Morris and P. Rowlands, Exploring Shipwrecks. (New York: Gallery Books, 1988): pp. 110-139.

See the Wikipedia sites for the HMS Vanguard and the Royal Oak.

This episode is a greatly revised version of Episode 292. . Photos courtesy of Wikipedia Commons, Satellite view courtesy of Google Earth.