Fanny Kemble

Today, another kind of radical. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Below the surface of early 19th-century London burbled an underground of women intellectuals. They came from many walks of life and they were interwoven. In public, most were wives of prominent men. In private they shook the very foundations of their society. Writers like Jane Marcet and Mary Somerville reshaped the texture of science education. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein warned about technological arrogance. Ada Byron promoted man-made intelligence of another sort when she wrote about Babbage's computers.

Harriet Grote is less familiar to us. Her husband George was a radical Member of Parliament. They ran with social reformers like John Stuart Mill. And as they promoted their political agendas she appears to've been the more intense and extreme of those two.

I mention her because in November, 1838, she opened a letter from Philadelphia. It was from her friend Fanny Kemble who said,

Friday morning we started from Philadelphia, by railroad, for Baltimore. ... Half the [rail] routes ... in America are temporary or unfinished -- one reason ... for the multitudinous accidents which befall wayfarers. ... Americans have all the impatience of children about [trying new things] ...

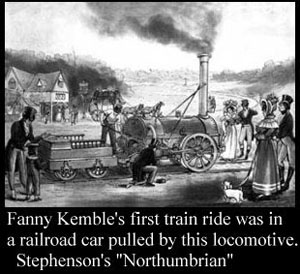

Behind a veneer of contempt lies her fascination with American energy. The letter goes on to detail her railroad trip in a country that'd had these new machines fewer than ten years. Here is a rare glimpse of an emerging technology. What makes it all the more significant is that, nine years earlier, Fanny Kemble wrote a famous description of her ride on one of the Stephenson locomotives.They were the British engines that'd defined early rail technology.

Behind a veneer of contempt lies her fascination with American energy. The letter goes on to detail her railroad trip in a country that'd had these new machines fewer than ten years. Here is a rare glimpse of an emerging technology. What makes it all the more significant is that, nine years earlier, Fanny Kemble wrote a famous description of her ride on one of the Stephenson locomotives.They were the British engines that'd defined early rail technology.

Fanny Kemble was a noted London actress, but she preferred to write. When she did an American tour in 1832 she met and married Pierce Butler, a Georgia plantation owner. That experience darkened as she sank into the horrors of slavery at close quarters. The marriage foundered, but her writings on slavery emerged to rally abolitionists some years later. (Kemble's and Grote's mutual friend, Harriet Martineau, also visited America. And she too fueled the cause of abolition.)

And yet, though these women played a big role in building the case against slavery,

that's not what caught my eye when I read about Kemble. Rather it was her constant attraction to the new technologies of transportation. Wherever she was, she took care to look closely and recount details. She writes,

We crossed the Susquehanna in a steamboat, which cut its way through the ice an inch in thickness with marvelous ease and swiftness. ... On other side, ... we again entered the railroad carriages to pursue our road.

These British women, bent on radical social reform, recognized a fundamental truth: As Fanny Kemble made clear, reform would rest on technology. In the end, technology is the agent that eliminates poverty, that makes slavery economically unattractive, and which lies at the heart of all social betterment.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

H. Grote, The Philosophical Radicals of 1832: ... (New York: Burt Franklin, 1866)

See also, the Wikipedia entry for Fanny Kemble and for George and Harriet Grote. Furthermore, this site gives one version of the passage quoted in the text. Much of Kemble's correspondence may be read on this site.

Images: Northumbrian image is wide circulated on the Internet. Source unknown. Fanny Kemble courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.