Stephenson's Locomotives

Today, the coming of rail. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I suppose we should credit Richard Trevithick with building the first steam locomotive. Railways already existed in 1804 when Trevithick designed a steam engine for a car that ran on rails. By then, he'd already built an early steam car. And rails were already being used to move horse-drawn wagons.

His first locomotive was pretty clunky. But, four years later, he ran a twelve mile-an-hour demonstration railway in London. After that people became seriously interested in steam locomotion.

Still, a mess of problems remained: Could you trust the friction of iron on iron for traction. Many early builders thought they needed a third line in the form of a rack of gear teeth. The engine could then drive a circular gear that engaged the rack, in-stead of relying on iron wheels to drive the train.

Where to put the boiler and the firebox? Where to put the cylinders and pistons? What kind of drive mechanism? Creating a steam railway from scratch was terribly complex. Finally, in 1829, the embryonic Liverpool and Manchester Railway tried to resolve many of these problems by means of a contest.

Their so-called Rainhill Trials tested many aspects of rail performance. The winner was Robert Stephenson's locomotive, The Rocket. Stephenson's father George was a rail pioneer who, like Trevithick, had come up through the trades. George had provided his son with a university education. The handsome and suave Robert looked a lot more like a British gentleman than a blacksmith.

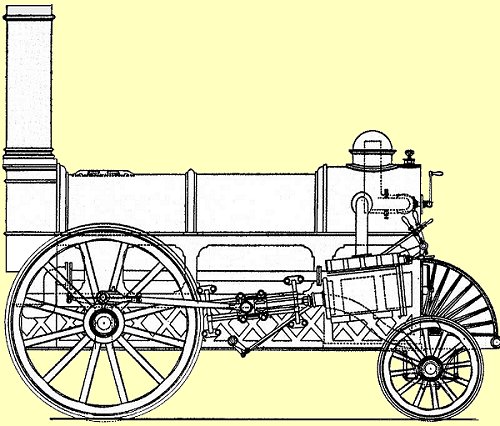

Robert was 26 when he won the trials, and he was already a seasoned locomotive builder. The next year he built his Northumbrian. Here, for the first time, he mounted the firebox directly under the boiler. That's the way steam locomotives were made ever after. With the Northumbrian,rail was no longer just a curiosity.

Robert was 26 when he won the trials, and he was already a seasoned locomotive builder. The next year he built his Northumbrian. Here, for the first time, he mounted the firebox directly under the boiler. That's the way steam locomotives were made ever after. With the Northumbrian,rail was no longer just a curiosity.

Joining the Northumbrian's demonstration run, between Manchester and Liverpool, was a beautiful young actress, Fanny Kemble. She was playing in Liverpool at the time, and had been invited to ride the new train with both George and Robert Stephenson.

When Kemble was older, she wrote a remarkably detailed account of the trip. She painted a fine picture of the visceral excitement she'd felt. She claims to have reached 35 miles-per-hour -- much faster than the official time. Perhaps the train actually did go that fast in a downhill stretch. But there's more to the story.

Kemble also said that she'd been enchanted, not by dapper young Robert, but by his father, George. "his face," she writes "is fine, though careworn, and bears an expression of deep thoughtfulness ... He ... certainly turned my head."

But what'd really turned her head? More than just the craggy Stephenson, I'll bet. Think about that heady moment. Think about movement, speed, and charisma, all rolled together. Fanny Kemble had been there at the beginning.Human transportation would, at last, leave horses behind. Earth was about to be reshaped.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

S. Smiles, The Story of the Life of George Stephenson, Railway Engineer.(London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1859.)

M. R. Bailey and J. P. Glithero, The Stephenson' Rocket: A history of a pioneering locomotive. (London & York: National Railway Museum, York, and Science Museum, London, 2002).

A. Burton, Richard Trevithick: Giant of Steam, (London: Aurum Press, 2000).

C. McGowan, Rail, Steam, and Speed: The Rocket and the Birth of Steam Locomotion. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

For the Fanny Kemble annecdote, see N. Faith, The World the Railways Made. (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1990): pp. 33-34.

The photo (by the author) above is of the locomotive firebox on the Durango Silverton Railway.

Line drawing of the Northumbrian locomotive.