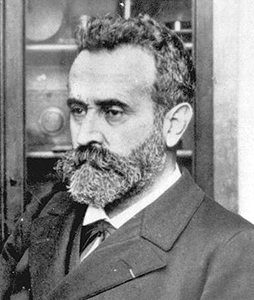

Alphonse Bertillon

by Andrew Boyd

Today, the measure of a man. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Imagine you're a law enforcement official in 1880. While booking someone who's broken the law, you ask yourself, "Haven't I seen this person before?" Checking name records isn't enough, since repeat offenders tend to lie.

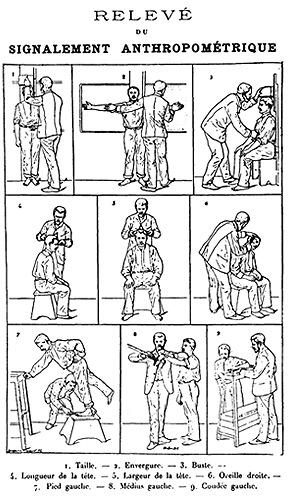

Today we rely on fingerprints and DNA tests. But that wasn't the case in the late nineteenth century. So we measured things, thanks to the work of Alphonse Bertillon. Height. Foot length. Ear size. Depth and width of the head. Bertillon called this method of identifying people anthropometry — literally, "human measurement." But it was popularly known as Bertillonage.

Today we rely on fingerprints and DNA tests. But that wasn't the case in the late nineteenth century. So we measured things, thanks to the work of Alphonse Bertillon. Height. Foot length. Ear size. Depth and width of the head. Bertillon called this method of identifying people anthropometry — literally, "human measurement." But it was popularly known as Bertillonage.

Bertillon came from a family of measurers. His father was the chief of the Bureau of Statistics in Paris, and he kept a slew of calipers, gauges, and other instruments at the family home. Bertillon's older brother helped found the International Statistics Institute and measured demographic trends.

But it was Bertillon's idea to physically measure criminals. His methods were developed while working for the Paris police department. After a successful experimental period, the methods were adopted. Bertillon also used photographs — front and side views, just like today's mug shots. But he downplayed relying too much on them, believing it was too easy for people to change their appearance. Still, the phrase, "[A] smile for the Bertillon studio" became street slang for "getting arrested."

But it was Bertillon's idea to physically measure criminals. His methods were developed while working for the Paris police department. After a successful experimental period, the methods were adopted. Bertillon also used photographs — front and side views, just like today's mug shots. But he downplayed relying too much on them, believing it was too easy for people to change their appearance. Still, the phrase, "[A] smile for the Bertillon studio" became street slang for "getting arrested."

Bertillon's methods proved so successful they were quickly embraced throughout the Western world. In retirement, the royal commissioner of police in Dresden, Germany wrote "Paris [was] the Mecca of Police, and Bertillon their prophet." An Illinois penitentiary clerk summed up Bertillon's impact in the United States and Canada saying, "The Bertillon system is ... becoming a fixture of permanent and universal usefulness ..."

Bertillon was even honored by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in The Hound of the Baskervilles. When one of Sherlock Holmes' clients calls Holmes the "second highest expert in Europe," Holmes indignantly asks, "Who's first?" Doyle's answer? "... the precisely scientific mind ... of Monsieur Bertillon ..."

In the end, the "French savant's" influence was short lived. By the early twentieth century, fingerprints had replaced Bertillonage. They were simpler and more accurate. But Bertillon left a legacy — a legacy of careful measurement. As anthropologist Jennifer Hecht reminds us, Bertillon "did a good deal of detective work, but he reportedly preferred measuring as a central occupation." And friends said he "worshiped precision to the point of idolatry." Perhaps it's a good lesson for all of us: use the utmost of care when seeking to measure a man.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

For a related episode, see FINGERPRINTS.

J. M. Hecht. The End of the Soul: Scientific Modernity, Atheism, and Anthropology in France. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

All pictures are from Wikimedia Commons.