Art Arfons and Speed

Today, a thought about folly and Function. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

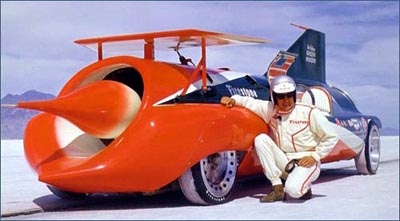

Robert C. Post is a serious historian with a recent article that reads more like a bittersweet memoir. He begins with a photo he took in 1991. It shows Art Arfons standing by his Green Monster No. 27, zipping up his fire suit. Well, that might need explaining.

The listed world land speed records began in 1898 when a French electric car reached forty miles-an-hour. (Locomotives were already pushing a hundred miles-an-hour, but they ran on tracks.) When a car passed the three hundred mile-an-hour mark on the Bonneville Salt Flats in 1935, that smooth hard salt surface then became the site of every subsequent record until 1983.

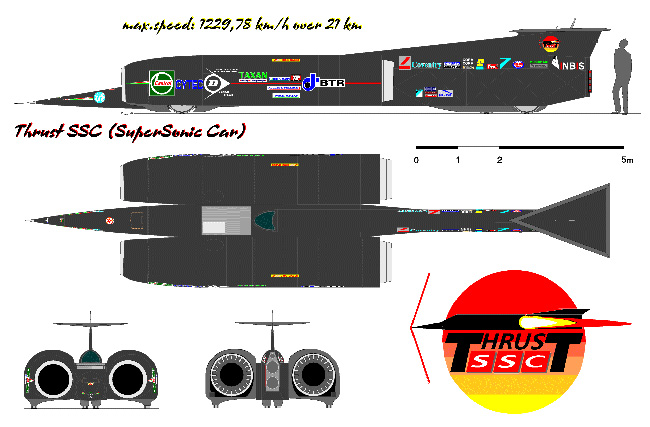

Then the British developed their ThrustSSC series -- big ten-ton twin-jet-powered beasts, too heavy for the Bonneville salt. Since then, all records have been made on the alkali surface of the Black Rock lake bed in Nevada. A ThrustSSC finally broke the sound barrier there in 1997.

Art Arfons, the designer and driver in Post's photo, had set three of the Bonneville records. When he appeared there in 1964 with his turbojet-powered Green Monster series, the record stood at 415 miles-an-hour. Thirteen months later he'd raised it to 573.

Art Arfons, the designer and driver in Post's photo, had set three of the Bonneville records. When he appeared there in 1964 with his turbojet-powered Green Monster series, the record stood at 415 miles-an-hour. Thirteen months later he'd raised it to 573.

But the 1991 photo shows 65-year-old Arfons. Three increasingly heavy cars had pushed the record another 50 miles-an-hour beyond his. Arfons had rejected the heft of those Thrust cars and was now committed to buoyancy. His latest Green Monster weighed less than a ton, but this was his third attempt. Two years before, he'd crashed. The next year, his machine suffered a debilitating vibration. Now he was off in a lonely part of the Flats for one last try with no fanfare.

He accelerated away in what seemed a good start. Then his afterburner failed and he simply coasted on out of sight, his equipment truck in pursuit. He was seen no more at Bonneville.

He did other daredevil stunts before he died at 81, three days after Evel Knievel's death. They buried Arfons with a wrench in each hand and a jar of Bonneville salt. And Post wants us to mull what it all meant. So I thought of Ben Franklin flying his kite in a thunderstorm -- of Dr. Rozier, first to fly in a Montgolfier balloon. I thought about how we cross the ocean at near sonic speed just because enough tinkerers chased intemperate and inexplicable goals. Recklessness is a big part of what got us to the moon.

The sixteenth-century cleric Erasmus once said that all learning, sacred or profane, leads to God. I take that as a metaphor for the quest for excellence. It can likewise seem headed in useless directions, before it unpredictably serves the general good.

Why else would the distinguished historian Post look at a former champion -- an old man continuing his quest even after it seems quixotic -- and come away with near reverence for what he sees.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

R. C. Post, The Land Speed Record and the Last Green Monster. Technology and Culture,Vol. 50, No. 3, July 2009. pp. 586-593.

See the Wikipedia sites on Land Speed Records, on Art Arfons, and on the Black Rock lake bed.

Images: Bonnevile Salt Flats and Black Rock Lake Bed (above) and the ThrustSSC diagram below are courtesy of Wikipedia Commons. The image of Arfons with his "Green" Monsterabove appears widely on the Internet; I do not know its origin.

Present Land Speed Record holder, the ThrustSSC