Rebecca Clarke

by Andrew Boyd

Today, a woman in conflict. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the peoplewhose ingenuity created them.

"Every now and then," she wrote, "… everything would suddenly fall into place … at these moments I was flooded with a wonderful feeling of potential power … Every composer … however obscure, is surely familiar with this sensation. It is a glorious one."

"Every now and then," she wrote, "… everything would suddenly fall into place … at these moments I was flooded with a wonderful feeling of potential power … Every composer … however obscure, is surely familiar with this sensation. It is a glorious one."

Rebecca Clarke was born in London in 1886. Her life stretched from the late Victorian era through the end of the 1970's — a period during which the role of women changed unimaginably. Clarke was a distinguished violist who studied for many years at London's Royal College of Music. She went on to make a living as a professional musician. Famed pianist Arthur Rubenstein went so far as to call her the "glorious Rebecca Clarke."

Clarke's story is interesting for what she achieved as a performer. But it's even more interesting for what she didn't achieve as a composer.

[Audio from beginning Rebecca Clarke's Morpheus]

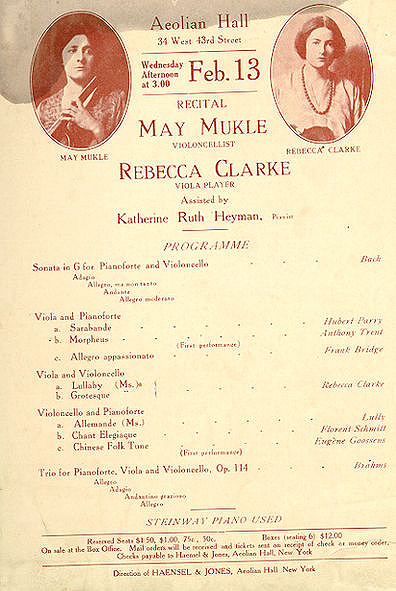

Observe that in the program shown here, Clarke performed her composition Morpheus under the pseudonym Anthony Trent. In later years, she commented "I thought how silly to have my name on the program yet again."

In 1919, Clarke's composition Viola Sonata tied for first place in the Berkshire Festival Chamber Music competition — an unheard of accomplishment at the time. It was rumored that Clarke hadn't written the piece by herself; that, in fact, it was impossible for a woman to have done so. Some rumors went so far as to suggest Clarke didn't even exist. It was too much to think a woman could write such wonderful music.

In 1919, Clarke's composition Viola Sonata tied for first place in the Berkshire Festival Chamber Music competition — an unheard of accomplishment at the time. It was rumored that Clarke hadn't written the piece by herself; that, in fact, it was impossible for a woman to have done so. Some rumors went so far as to suggest Clarke didn't even exist. It was too much to think a woman could write such wonderful music.

Clarke's success led to a blossoming of creative output, but it quickly slowed. At times in her life, she didn't compose at all. And when she did, she often failed to publish. Much of her work now belongs to her estate or is simply lost. The compositions we know of are rare pearls of great beauty.

Why, then, didn't Clarke compose and publish more music? There's no simple answer. But historian Liane Curtis argues that while Clarke and society viewed playing the viola as acceptably feminine, the act of composing wasn't.

It's a sad thought — that creativity could conflict with sense of self — that, because of societal norms, Rebecca Clarke's passion for writing music left her feeling at odds with her womanhood. Thankfully, with every newly educated generation, we help free the creative spirit locked within each of us.

[Audio from end of the first movement of Viola Sonata]

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Many thanks to Erwin and Susan Fishman for bringing the story of this delightful musician to my attention.

L. Curtis. “A case of identity.” The Musical Times, May, 1996. Taken from the web site of the Rebecca Clarke Society: http://www.rebeccaclarke.org/pdf/identity.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2009.

Audio taken from Rebecca Clarke: Viola Sonata; Dumka; Chinese Puzzle; Passacaglia on an Old English Tune. Naxos, 2009.

All pictures are from Wikimedia Commons.