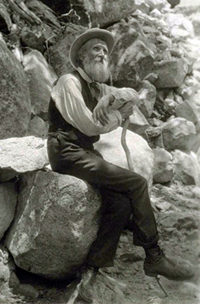

John Muir

by Andrew Boyd

Today, an unlikely engineer. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

He's been called the Wilderness Prophet, Citizen of the Universe, and Father of Our National Parks. John Muir's name is most closely associated with the Sierra Club and Yosemite National Park. But he wasn't just a naturalist, world traveler, and author. He was an engineer.

Muir was born in 1838 in a small town in Scotland. His family emigrated to Wisconsin when he was eleven. Forbidden by his father to waste chore time toying with mechanical devices, Muir would rise early in the morning, working by candlelight in the family cellar. He built waterwheels, clocks, automatic horse feeders, a clock-driven desk, and even an "early rising" machine — a device that pulled a leg from under his bed at a specified hour. Muir displayed some of his inventions at the Madison State Fair in 1860. They generated so much interest he was able gather enough money to enter the University of Wisconsin the following year.

Muir reveled in his education. Mathematics, chemistry, physics, the classics. But two years into his studies he left. His calling was elsewhere, though he had yet to discover it. For four years Muir supported himself as an engineer in woodworking factories. But when an accident temporarily blinded him, Muir made a decision. "I bade adieu to mechanical inventions," he later wrote, "determined to devote the rest of my life to the study of the inventions of God."

He began his quest with a "thousand mile walk" to the Gulf of Mexico. From there, he sailed to Cuba, crossed the Isthmus of Panama, and eventually arrived in Northern California. His travels would take him to all of the habitable continents. But it was the beauty of California's Sierra Nevada Mountains and the Yosemite region that captured Muir's heart. He tirelessly promoted wilderness conservation through his writings and personal influence. Muir's many books and articles revealed a passion that moved others to action. By his death, Muir had completed his conversion from engineer to naturalist.

As Muir's ideology evolved, he never expressed contempt for engineering. A watermill grinding. A clock ticking. To Muir, their operation was but one facet of the natural world he so loved. But his early mechanical creations seemed Lilliputian compared to what he observed all around him.

"Nature is ever at work building and pulling down," he wrote, "creating and destroying, everything whirling and flowing, allowing no rest but in rhythmical motion, chasing everything in endless song out of one beautiful form into another." To Muir, God was indeed a clockmaker — if not the clock itself. And Yosemite, the giant sequoia trees, and all the world's natural wonders, were viewed as the greatest expressions of the Divine Engineer.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Some delightful pictures of John Muir's inventions can be found at the Wisconsin Historical Society web site: http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/search.asp?id=1581.

John Muir: A Brief Biography. From the Sierra Club John Muir Exhibit web site: http://www.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit. Accessed October 7, 2008. See the Biography tab.

Quotations from John Muir. From the Sierra Club John Muir Exhibit web site: http://www.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit. Accessed October 7, 2008. See the Writings by John Muir tab.

Pictures courtesy of Wikipedia Creative Commons.