Kill Devil Hills

Today, we watch invention unfolding. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

So much is known about the Wright Brothers, I've stopped expecting new insights. However, we were just given a copy of Wescott and Degen's book, Wind and Sand -- a collection of Orville's and Wilbur's letters and photos from 1900 to 1903. That's the period they spent on the outer banks of North Carolina. Suddenly, their work takes on a powerful texture of reality and intimacy.

The Wrights had taken an interest in flight the year before. When they flew a 5-foot model glider, it seemed clear that a flying machine was within grasp. The next summer they studied weather maps looking for reliable winds blowing across flat empty land. They wrote to the Weather Bureau in the small fishing village of Kitty Hawk, and got a very encouraging letter back from William Tate, the Kitty Hawk postmaster. So they went to Kill Devil Hills, just south of Kitty Hawk. And the Tate family proved to be profoundly helpful to the two brothers over the next three years.

The Wrights had taken an interest in flight the year before. When they flew a 5-foot model glider, it seemed clear that a flying machine was within grasp. The next summer they studied weather maps looking for reliable winds blowing across flat empty land. They wrote to the Weather Bureau in the small fishing village of Kitty Hawk, and got a very encouraging letter back from William Tate, the Kitty Hawk postmaster. So they went to Kill Devil Hills, just south of Kitty Hawk. And the Tate family proved to be profoundly helpful to the two brothers over the next three years.

The Wrights worked with exquisite scientific care. Their diaries and letters are filled with wry commentary and full details of their adventure. They also learned photography and left a stunning visual record of their work.

During that first autumn they made large unmanned tethered kite-gliders. They flew them in those steady winds and controlled them with cords from the ground. They'd set up a tent and they subsisted by fishing and eating a lot of canned goods.

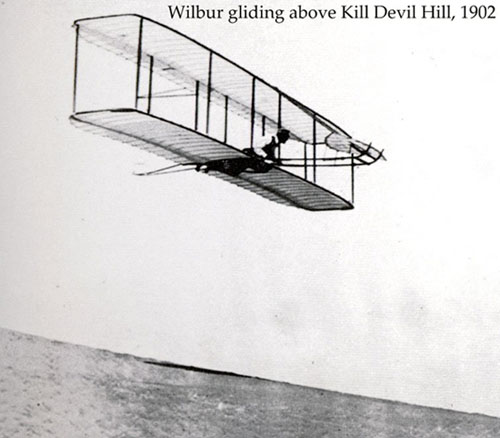

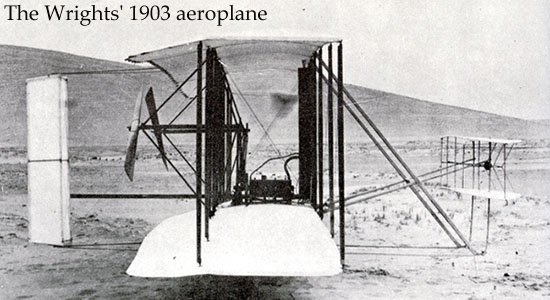

They built a frame building and a well-organized base camp in 1901. Now they made manned glider flights. In 1902, they created more gliders and honed the design of a proper airframe. In 1903 they returned from their winter in Ohio with a wind tunnel and an airplane engine of their own design. On December 17th they finally made four flights, and they made history, in a powered aeroplane.

They still had far to go. Now they had to go back to Ohio and set out to create aeroplanes that no longer needed a twenty-mile-an-hour-headwind to take off, planes that could make turns and stay aloft longer. All the while, their successes were largely ignored by the media. In 1904, the editor of a magazine titled Gleanings in Bee Culture, watched their trials. Then he wrote:

When Columbus discovered America he did not know what the outcome would be ... In a like manner these two brothers have probably not even a faint glimpse of what their discovery is going to bring.

Well, he nailed it. Wilbur died before WW-I and left Orville to be appalled as airplanes took part in the slaughter. They'd made their first sales to the Army with the ago-old thought that their machines might make war obsolete.

But then war and necessity never have been strong drivers of invention. This very personal record of those days in Kill Devil Hills helps us to fully grasp the purposeless creative joy that propelled two highly-focused young men into the sky.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

L. Wescott and P. Degen, Wind and Sand: The Story of the Wright Brothers at Kitty Hawk. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Pubs, 1983). My thanks to Margaret Culbertson for this intriguing book. All photos courtesy of the Library of Congress.