The PaleoClock

Today, a very slow clock. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Hurricane Ike's 2008 visit to Houston did a lot of damage. That included tearing off part of our roof, and soaking two of our nice rugs. When we took them in to be cleaned, I noticed an odd clock on a table in the rug shop. So I asked the owner about it.

He's Tom Legg -- former BP geologist, now a dealer in oriental rugs. But show me any geologist and I'll show you a lingering love of old rocks. His clock is all about the rocky ages of our planet Earth. It marks off, not hours, days, or even years. Rather, its single hand makes one lap about its face every billion years. That's right; I did say one billion years per revolution!

He adds, tongue-in-cheek, that it should report its progress on that long rotation by chiming once every million years. Then he adds that, if it misses a chime, you should call him. (I guess he'll send out a repair team.) The tip of that single hand takes one human lifetime to move a millionth of an inch.

He adds, tongue-in-cheek, that it should report its progress on that long rotation by chiming once every million years. Then he adds that, if it misses a chime, you should call him. (I guess he'll send out a repair team.) The tip of that single hand takes one human lifetime to move a millionth of an inch.

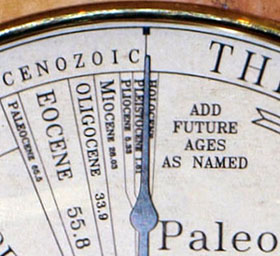

Starting where we'd expect to see three-O-clock, this so-called PaleoClock is marked off in geologic eras beginning with the Pre-Cambrian. From five-thirty to nine is the Paleozoic Era, and from nine to eleven the Mesozoic with its ancient dinosaurs. The last twelfth of the dial is the Cenozoic Era.

But right now the hand points to high noon -- the beginning of th e Holocene Era. That's when the human animal species came into dominance. The Holocene began after the last Ice Age and Legg tentatively continues it for a few million years beyond the present.

e Holocene Era. That's when the human animal species came into dominance. The Holocene began after the last Ice Age and Legg tentatively continues it for a few million years beyond the present.

He's quick to say that should not be taken as hubris -- he simply had to make that slice wide enough to write the word Holocene in it. After that, his clock face continues for another 200 million years of an unknown future. He also points out that we must replace his clock's face with a new one every billion years.

You might wonder if Legg is just putting us on. We'd have to live for hundreds of thousands of years to detect any movement at all. He could just as well have glued a stationary hand on a dummy clock. So he opens a side door to show me his gear train. An electrical clock motor drives a series of 34 gears on 17 shafts. Each pair reduces the speed of the next by a factor of five. The visible twelve-hour rotation of the first gear is finally reduced by a factor of 5-to-the-17th-power at the clock hand shaft.

This clock does exactly what he claims. And it's nice workmanship to boot -- a fine oak cabinet with the face mounted in a marble slab. He'd meant to market them, but found he couldn't make them for a low enough price. We can, it seems, only admire this -- or one of five others that he's built to date.

So this was my moment of Zen amidst the frustrations of putting life back together after the tempest. It's reassuring to know that our troubles cannot last long enough to be seen even by an electron microscope on the face of this strange clock -- this means for seeing our lives against the real scale of passing time.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Tom Legg's store is The Rug Collector, 2354 Bissonnet St., Houston, TX, 77005. The name PaleoClock is trade-marked. The gear reduction of 517means that the last shaft turns at 1/762,939,453,125th the speed of the first. Photos by J. H. Lienhard. CLICK HERE for a photo of the whole clock.