The Petersburg Crater

Today, the Petersburg Crater. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Those of us who read Cold Mountain, or saw the fine movie version, carry a mental image of Earth suddenly erupting before our eyes at the Battle of Petersburg, Virginia. The movie recreated the real-life Petersburg blast with stunning and chilling accuracy. Now, I find an 1887 Century Magazine with four articles about that day in July, 1864. They're by survivors of war, struggling to sort out this terrible experience, just 23 years earlier -- this Union Army disaster of epic proportions.

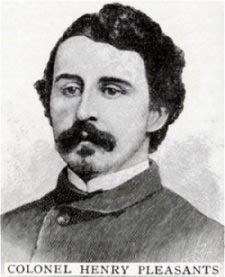

Grant had surrounded Petersburg, a supply hub twenty miles south of Richmond. Nine months later, he would take the town, but only after a series of ghastly battles; and his victory would lead to the surrender at Appomattox. In the early days of the blockade, a mining engineer, Henry Pleasants, now a Union colonel, went to General Burnside with a plan to tunnel under the Confederate trenches, blow them up, and open a hole for the Union forces.

Grant had surrounded Petersburg, a supply hub twenty miles south of Richmond. Nine months later, he would take the town, but only after a series of ghastly battles; and his victory would lead to the surrender at Appomattox. In the early days of the blockade, a mining engineer, Henry Pleasants, now a Union colonel, went to General Burnside with a plan to tunnel under the Confederate trenches, blow them up, and open a hole for the Union forces.

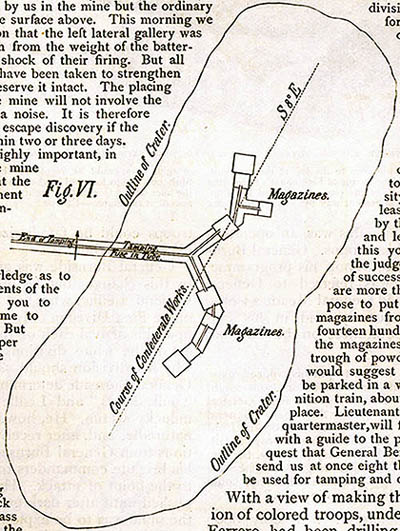

Burnside agreed, but Generals Grant and Meade didn't take it seriously. They provided no extra resources. Pleasants had his troops dig a 500-foot tunnel that fanned out in a T-shape, fifty feet below Confederates lines. An air shaft, just out of enemy sight, provided an exhaust draft driven by a fire in the tunnel. They loaded four tons of gunpowder in the T-section and waited.

Pleasants also trained a division of Black soldiers. They were to charge around the sides of the crater after the blast. Then, just before the explosion, General Meade told Burnside, Don't use the inexperienced Black troops; replace them with untrained white troops. He feared the Black troops would suffer huge casualties and he would look bad in the Northern press. It was a very poor decision.

The blast went off at dawn, and it was horrific. Hundreds of Confederate soldiers died -- but far more survived. The replacement Union assault force fell back from the flying mountain of dirt, then surged forward in a confused mass to stare into the crater. While they milled about in disorder, the South regrouped.

The Union soldiers were finally ordered to charge -- not around the pit, but straight into and across it. The scene was hellish chaos -- those in back pushed those in front. They were trapped in debris while the Confederates shot them to bits. Hundreds died in what's been called The Great Turkey Shoot. The Black soldiers were finally ordered into the mess. They joined the tally of 500 Union troops lost.

Century Magazine's four articles remind me of watching the movie Rashomon. Each writer formulates his own tale of horror and heroism, and they all conflict. Well, of course they do. War is confusion. Blame touches everyone and no one. Grass may've grown over the crater, but the scars, the claims, and the distortions still lingered then -- and they continue to hover over the unsettling story of the Petersburg Crater, even now.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

W. H. Powell, The Tragedy of the Crater;

G. L. Kilmer, The Dash Into the Crater;

H. G. Thomas, The Colored Troops at Petersburg;

G. L. Kilmer, Assault and Repulse at Fort Stedman.

The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, Vol XXXIV, No. 5, September, 1887, pp. 760-790. All images from this source, including This mural of an artist's conception of the Battle.

See the Wikipedia article on "The "Battle of the Crater".

C. Frazier, Cold Mountain. (New York: Grove Press, 2006 paperback).

The opening scene of the movie Cold Mountain, the explosion re-enactment, is on You-Tube.

My thanks to Bobby Marlin, UH Library, for his counsel. The musical tag in the audio is taken from the Cold Mountain movie soundtrack, Tim Eriksen playing Am I Born to Die?(Columbia Records, CK86843, Track 7).

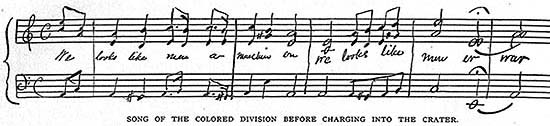

The Century articles include so much more: Stories came back from Andersonville prison about Union soldiers who'd curried Southern favor just, before they were captured, by bayoneting their Black comrades in the crater. Or a different kind of chilling scene, shortly before dawn, when the Black troops were told they'd been pulled from the charge: The news was followed by a long, long silence. Then a single voice lifted in song -- more voices entering in harmony. Soon all were singing: "We looks like men a marchin' on, we looks like men-er-war."

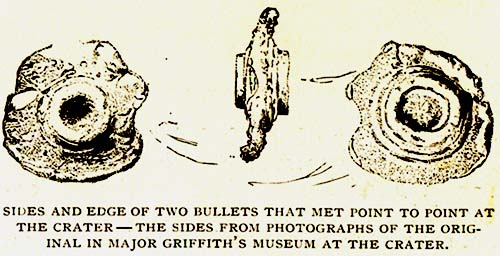

This strange image suggests the intensity of the fight: Confederate and Union bullets that collided. What would the density of fire have to've been for this extraordinary coincidence to occur?

The mouth of the Union Tunnel in 2010. Photo by John Lienhard

In the Crater as seen by the Union Troops, but 146 years later. Photo by John Lienhard