In Praise of Sulfur

Today, in praise of sulfur. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

One bottle in my boyhood chemistry set held pure sulfur. I melted sulfur, burned it, used it to make gunpowder. And when that bottle ran out, I spent my pennies at the drugstore to buy more. We no longer have such contact with raw sulfur.

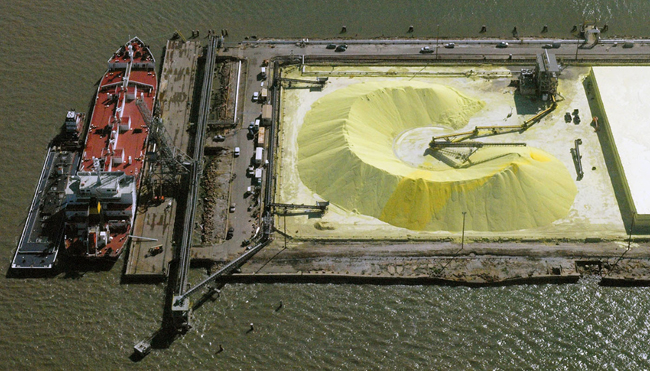

So I was delighted to find a sulfur lump on the road near a sulfur plant, yesterday. Across the fence were great yellow piles. The Arabic verb saffara means to make yellow. That word is connected to sulfur, and the yellow spice saffron -- both brilliant yellow. Sulfur is the ninth most plentiful element in the universe. Much of Earth's sulfur is combined with other materials, from which it can be extracted. But pure elemental sulfur is plentiful in salt domes on the Texas and Louisiana coasts where muck and quicksand make it almost impossible to mine.

So I was delighted to find a sulfur lump on the road near a sulfur plant, yesterday. Across the fence were great yellow piles. The Arabic verb saffara means to make yellow. That word is connected to sulfur, and the yellow spice saffron -- both brilliant yellow. Sulfur is the ninth most plentiful element in the universe. Much of Earth's sulfur is combined with other materials, from which it can be extracted. But pure elemental sulfur is plentiful in salt domes on the Texas and Louisiana coasts where muck and quicksand make it almost impossible to mine.

So let us meet a German immigrant named Herman Frasch. In 1882, Frasch was a 31-year-old consulting chemist in Cleveland. He'd just sold a process to a Canadian Company for removing sulfur from oil. As a result, Standard Oil set him up in a major research laboratory to deal with sulfur-related problems.

So let us meet a German immigrant named Herman Frasch. In 1882, Frasch was a 31-year-old consulting chemist in Cleveland. He'd just sold a process to a Canadian Company for removing sulfur from oil. As a result, Standard Oil set him up in a major research laboratory to deal with sulfur-related problems.

Sicily then held a virtual monopoly on sulfur. Their deposits were minable, while ours were not. So Frasch went to work on means for getting at our coastal sulfur. In 1887, he received a patent for an extraction process. He sank three concentric pipes down into a sulfur lode. The outer pipe carried pressurized water, heated just above sulfur's melting point. The middle pipe carried compressed air which blew the sulfur-water-air mix back up the third pipe in the center.

All that took a lot of energy. But these reserves lay right in the coastal oil fields so fuel was abundant. That's how East Texas and Louisiana became major sulfur producers by the early 20th century. Good thing for us, since Italy was allied with Germany at the outbreak of WW-I and we had to have sulfur for munitions.

We no longer hear as much about sulfur. Texas once produced over eighty percent of America's sulfur using the Frasch process. But sulfur is still a major Texas product! Only now it comes from cleaning up fossil fuels.

We no longer hear as much about sulfur. Texas once produced over eighty percent of America's sulfur using the Frasch process. But sulfur is still a major Texas product! Only now it comes from cleaning up fossil fuels.

So why do we want all that sulfur? Well, we use it in metals and medicines, fertilizers and fibers, wood pulp and rubber production. Sulfur itself is odorless and nontoxic; but it combines to make scary stuff like sulfuric acid. When you and I think about sulfur, we think of the rotten-eggs smell of hydrogen sulfide, H2S. What's less known is that the H2S in our bodies aids memory and helps our heart. It's one of beneficial chemicals in garlic.

So let's lay aside our visions of hell and brimstone for a moment as we look at those pelican-circled piles of sulfur along the Texas coast. There's beauty in that gleaming yellow trove -- more useful than mere gold, and as lovely as a daffodil.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

See the Wikipedia articles on sulfur and on Frasch.

I am grateful to Lewis Wheeler, UH Mech. Engr. Dept, for suggesting the topic. All photos are by JHL except that of Frasch, which is courtesy of Wikipedia. Sulfur is spelled sulphur in Great Britain. And the misspelling sulfer is so common as to be regarded almost as an alternate.