Inventing the Hyperlink

Today, we invent the hyperlink. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Hyperlinks are now commonplace. But they were new and wonderful in the early 1990s. Just a few web pages had notes telling us that a mouse click would take us from this spot to some related page. Today, the color blue signals that a word is a stepping stone to in-depth information. We take this enormous convenience for granted.

We might trace the hyperlink back to the early 19th-century invention of the roller press and the explosion of cheap books. We were beset with a flood of information that had to be managed. In 1874, a student at Amherst College, Melville Dewey, saw that the problem of finding the specific information we wanted was growing hopelessly complex. Three years later, he'd developed his famous decimal system for classifying books and retrieving information.

Then, in 1895, another young student, the Belgian Paul Otlet, took an interest in managing the still-growing information flood. Dewey's system was in wide use, but Otlet realized that could lead to only one particular source. If you wanted more, you had to start over.

Then, in 1895, another young student, the Belgian Paul Otlet, took an interest in managing the still-growing information flood. Dewey's system was in wide use, but Otlet realized that could lead to only one particular source. If you wanted more, you had to start over.

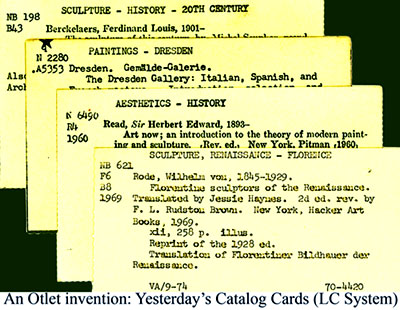

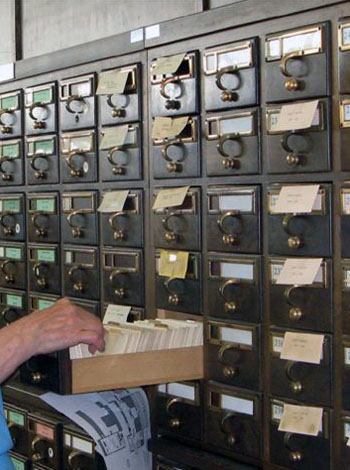

So Otlet began amassing his own index to the literature. He developed the chests of three-by-five-inch cards that served libraries for a century. But he also created his own universal decimal catalog. It resembled the Dewey system, but he included a scheme for cross-linking subjects. For a book on sulfur in steel, he'd use a colon to connect the call number for iron to that for sulfur. That created an independent call-up for the book -- a kind of hyperlink. Once you found the subject of iron, you'd find a link to sulfur. You'd retrieve that book on sulfur steels.

Otlet wanted to do much more. He really did envision using his search scheme in an embryonic form of our Internet. He built an information center -- his Mundaneum -- a place that used all kinds of mechano-electric devices to access his cards.

For a while, he ran a commercial information service. But economic and political turmoil swept Europe, and Hitler came to power. At that point, Otlet was envisioning what he called an electric telescope -- a system combining telephone, television, sound recording, and microfilm to deliver information world wide.

Then the NAZIs entered Belgium. They seized the Mundaneum, so they could use the building for a museum of NAZI "art." What they failed to destroy, Otlet had to move into a warehouse. He seemed to've been beaten, and he died five years later.

Now his Mundaneum has been rediscovered and made into a Museum. Otlet is being celebrated as Internet Inventor du jour. Well, no one person invents anything so large, but he was certainly a pioneer. Nor are we far off in calling him "the inventor of the hyperlink."

One Otlet legacy is secure: His Universal Decimal Classification or UDC may be hardly known in the US. We like to use the Dewey Decimal or Library of Congress Classification. But in Europe and Asia, his UDC remains the primary way that people track their books.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Wright, The Web Time Forgot, New York Times, Science Times,Tuesday, June 17, 2008, pp. D1 and D4. Otlet photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

See also the Encyclopaedia Britannica entry, Library: Classification.

See also, the Wikipedia Otlet article, the Wikipedia article on hyperlinks, and this OCLC Dewey Timeline. And here is the home page of the UDC Consortium.

Melville Dewey was also interested in spelling reform. He tried to change his name to Melvil Dui. The first-name change stuck but Dui did not. It was he who changed the spelling of catalogue to catalog. The beginning of the Dewey Decimal Classification and Relative Index, 18th ed. (New York: Forest Press, Inc. 1971) begins with this 1926 statement by Dewey:

Orijin and growth The plan of this Clasification and Index was developt erly in 1873, the result of long study of library economy as found in hundreds of books and pamflets, and in over 50 personal visits to libraries. This study convinst me that usefulness of libraries myt be greatly increast without aded expense.

I am most grateful to Libbie Crawford, Dewey Decimal Classification Product Manager for OCLC, and Jack Hall, UH Library cataloger, for their valuable counsel.

Otlet-type cards in a Dewey decimal card catalog (photo by Andrea Sutcliffe)