The Footnote Makes the Historian

by Rob Zaretsky

Today, our guest, historian Rob Zaretsky, takes the measure of the footnote. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

When people learn that I'm a historian, they tell me, "I loved history in my school days!" But I often wonder if this is another way of saying, "At least I knew when to get a real job."

Oversensitive? Maybe, but I'm not alone: historians have historically worried about justifying history writing. Modern historiography was born in the 19th century with German pioneers like Leopold von Ranke, who turned us into more than, well, storytellers. In an age of scientific method, historical practice also seemed to require better foundations -- a base on which, Ranke claimed, we can say how the past really was.

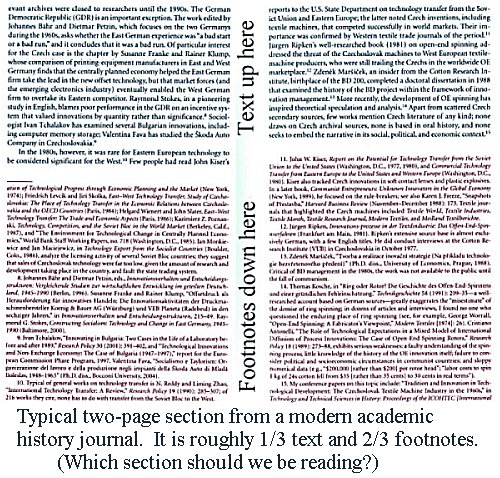

Enter the footnote: over the layers of scholarly references poured at the floor of the page, the enterprise of scientific history would be established. The footnote offered objectivity: the pageant of tiny phrases running across the page's bottom, bristling with numbers and abbreviations, smacked of science. Like labels on medicine containers, footnotes were prescriptive. Forget the joys of storytelling: history was now a discipline, rigorous and impartial.

Ranke's aim was heroic: the historian, armed with the footnote, would battle the shadows of the past. Yet as Anthony Grafton suggests, Ranke's era actually marks the demise of the footnote -- at least when compared to Enlightenment historians. Consider Edward Gibbon's History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. His footnotes are scholarly, but also artful. Time and again, Gibbon takes away with the footnote what he gives with the main text. Thus he insists the historian should not comment on matters of faith. But in a footnote on the same page, he observes that saints like Bernard of Clairvaux, who recorded the many miracles of friends, never noticed his own. Fortunately, Gibbon concludes with a faint smile, Bernard's own miracles were "carefully related by his companions and disciples."

Ranke's aim was heroic: the historian, armed with the footnote, would battle the shadows of the past. Yet as Anthony Grafton suggests, Ranke's era actually marks the demise of the footnote -- at least when compared to Enlightenment historians. Consider Edward Gibbon's History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. His footnotes are scholarly, but also artful. Time and again, Gibbon takes away with the footnote what he gives with the main text. Thus he insists the historian should not comment on matters of faith. But in a footnote on the same page, he observes that saints like Bernard of Clairvaux, who recorded the many miracles of friends, never noticed his own. Fortunately, Gibbon concludes with a faint smile, Bernard's own miracles were "carefully related by his companions and disciples."

In a word, Gibbon always drops the other shoe in his footnotes. It is on the page's floor that he pulls the rug out from under the story written above. Gibbon's erudition was as sharp as his tongue: when a fellow classicist attacked him for shoddy scholarship, he invited the poor man to call at his house "any afternoon when I am not at home." If he had gone, he would've seen a library amassed by a man who, as a child, preferred reading about the "dynasties of Assyria and Egypt" to playing cricket.

Gibbon was as learned as his scientific descendants, but was also far more mischievous. Like his Enlightenment contemporaries, Gibbon could not help but season his scholarship with skepticism. Thanks to the ironic uses of the footnote, history was an invitation to laugh at us ourselves. The tragedy of the footnote, as Grafton concludes, is that what began as high art becomes tedious routine. (Though I should add, by way of footnote, that Grafton's book disproves this very claim.)

I'm Rob Zaretsky, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Robert Zaretsky is professor of French history in the University of Houston Honors College, and the Department of Modern and Classical Languages. (He is the author of Nîmes at War: Religion, Politics and Public Opinion in the Department of the Gard, 1938-1944. (Penn State 1995), Cock and Bull Stories: Folco de Baroncelli and the Invention of the Camargue. (Nebraska 2004), co-editor of France at War: Vichy and the Historians. (Berg 2001), translator of Tzevtan Todorov's Voices From the Gulag. (Penn State 2000) and Frail Happiness: An Essay on Rousseau. (Penn State 2001). With John Scott, he is co-author of The Rift: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume and the Quarrel that Shook the Enlightenment. (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2007).

Grafton, The Footnote: A Curious History. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1997).