Balsa Wood

Today, we build with balsa wood. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Model airplanes were the dream-factory of my early years, with their wonderfully tough frameworks of feather-light balsa wood. I would bend slender balsa stringers about thin balsa bulkheads. I'd cover the frame with a drum-tight skin of impregnated tissue paper and get a half-ounce wing or body -- powerfully strong and beautifully formed. The strength-to-weight ratio of those gossamer airplanes was astonishing.

Balsa is one of the lightest woods. It comes from the Ochroma pyramidale tree, which grows in South and Central America. Actually, its more of a huge flowering weed than a tree. It lives in isolation -- it's impossible to create a balsa forest.

Balsa is one of the lightest woods. It comes from the Ochroma pyramidale tree, which grows in South and Central America. Actually, its more of a huge flowering weed than a tree. It lives in isolation -- it's impossible to create a balsa forest.

South American Indians have long used balsa boats, but modern boat and airplane makers were slow to adopt it. It's very soft. We can easily crush it. We can score it with our thumbnail. But it's strong in tension and it's shockproof.

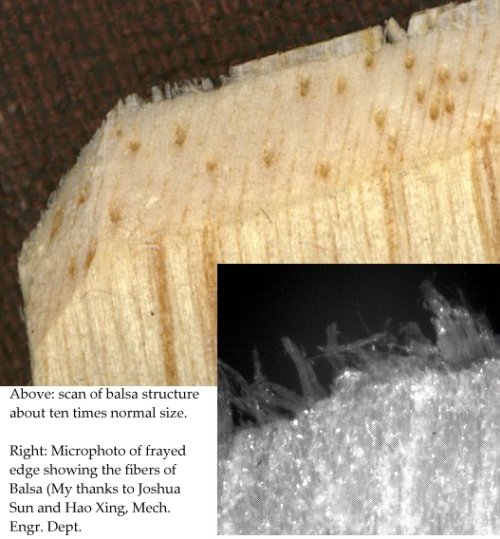

The use of balsa wood can be understood by comparing it with a structural I-beam. That's a steel beam whose cross section looks like the capital letter I. The flat parts on the top and bottom of an I-beam carry the load. All the middle part has to do is separate the top and bottom. The middle needn't be very strong. So the trick is to use balsa to make the middle of a sandwich with a tough skin outside -- rather like we made model airplanes.

During WW-II, airplane builders used this kind of construction in the de Havilland Mosquito -- a light attack bomber that was viciously effective in Europe. When enemy shells passed through it, they didn't start cracks or even much weaken the structure. The Mosquito bomber had a worse enemy in South Pacific micro-organisms that ate the casein glue holding it together.

But that could be remedied with other glues because the open grain-structure of balsa wood makes it very easy to glue. Today, large, light, high-speed boats hulls are being made of one-inch balsa with a hardwood veneer. They're tough, resilient, and light -- and very good under the wave-pounding inflicted on a high-speed boat. Surfboards were, for a season, made with balsa cores.

The outgrowth of this is a new class of composite materials that work the way those balsa boats and airplanes do. Plywood was one of the earliest. It got around the directional weakness of wood by alternating the grain direction in its layers.

Modern composites are made of strong fibers, carbon or silicon, embedded in a plastic matrix. The result is very light, but it can be stronger than steel. Now airplanes are being made of composites. So too will be a new generation of space vehicles.

And it has to be more than coincidence that these materials originated in the minds of a generation of model-airplanes builders -- people touched by the tactile experience of handling such a wonderfully beautiful and buoyant material as balsa.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Rhodes, O.T., 'Fragile' Balsa. Mechanical Engineering, February 1989, pp. 48-54.

For more on balsa, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balsa

This is a revised version of Episode 233.