Deslandes' Glass

Today, we're left behind by the revolution. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Europe and America went through revolutions in the late eighteenth century. Great Britain's was relatively bloodless since it was an Industrial Revolution. But then, in some sense, the others were as well. In all cases, the middle class wrested control from a ruling elite, and laying claim to technology was a part of it. Perhaps that's why a French manufacturer, Delaunay Deslandes, was bypassed by those revolutions.

Deslandes joined the French Royal Glass Works in 1752, when he was 30. It took him a scant six years to become its general manager -- a job he held for 31 years. When he died, he left a manuscript: On the History of Glass Making-- actually more a memoir than a history, but it revealed the workings of one French factory while the English Industrial Revolution was fomenting.

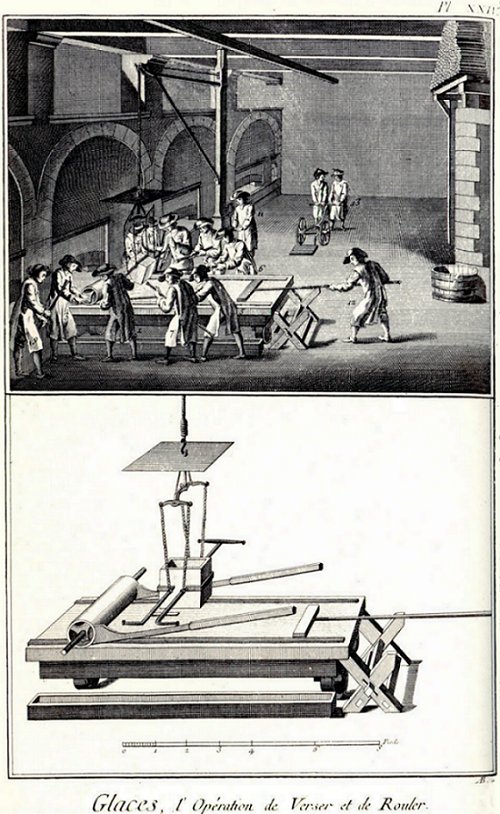

Deslandes clearly found a vocation in his work. He took great pride in it. French plate glass was the best flat glass in the world when he was young. It was far superior to the so-called crown glass or broad glass made in other countries. The French cast large plates in very hot molten glass, then rolled them out and ground them into high-quality panes for windows and mirrors.

Deslandes tried to learn what the British already knew about the chemistry of coal-burning. It takes very clean, intense heat to make plate glass. The British knew a great deal about that from using coal to produce iron and steel.

Alas, while British industrialists like Watt and Wedgwood created seminars with scientists and philosophers, French manufacturers were isolated from intellectuals. Information didn't flow the way it did in Great Britain. As the Industrial Revolution rolled on, France lost its ascendancy even in glass-making.

Deslandes held progressive ideas about labor and management. He instituted workers' benefits; he knew his product depended on workers' pride and craftsmanship. It smacked of benevolent paternalism. Still, he was always there in the thick of it, no managing from distant estates. Every time glass was poured, he arrived in full formal dress to observe and make ceremony of the act.

He retired to a house near the factory. When he was 82, a bitter cold front threatened a company waterwheel with icing. Deslandes joined the workman fixing it and died of exposure as a result. The company that had been his life finally claimed his life.

If so good and honorable a man represented France, then we might well wonder what France lacked that England had. Well, Deslandes sustained an old order, shaded from the new winds of science and individualism. It took more than good masters to survive the harsh winds of 18th-century revolution. It took people and institutions that would seize change. It took people willing to see their world turned inside out, and remade from the ground up.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

J. C. Harris and C. Pris, The Memoirs of Delaunay Deslandes. Technology and Culture, Vol. 17, No. 2, 1976.

This is a greatly revised version of Episode 245.

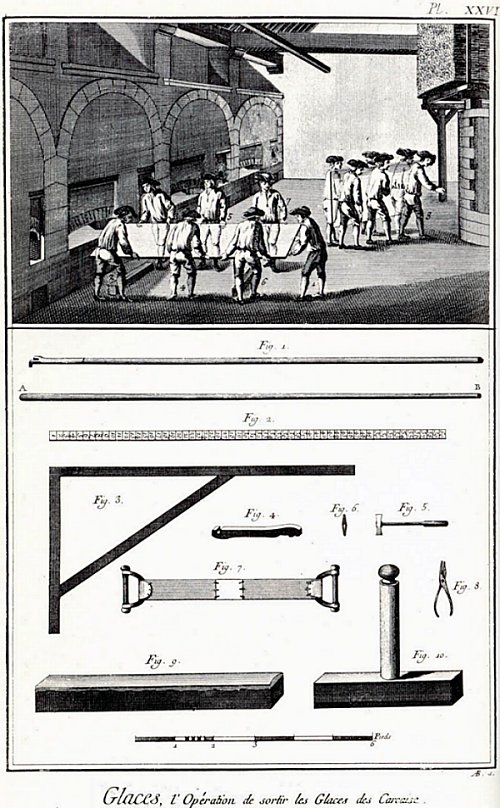

Below: Two images from Diderot's 1771 Dictionary of Science, Arts, and the Trades: Upper image shows the rolling-out of plate glass as Delaundes might've done it. Lower Image: a group of men handling a large plate of glass.