Diderot's Encyclopedia

Today, we talk about revolutions and encyclopedias. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Encyclopedias date back to 2nd-century Rome. But Ephraim Chambers's English encyclopedia broke new ground in 1728. Its title, typical of the time, sounds more like a table of contents:

Cyclopaedia; or a Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, Containing an Explication of the Terms ... in the Several Arts, both Liberal and Mechanical ... etc., etc. ...

The new idea here is mechanical arts. Earlier encyclopedias were never that down-to-earth.

The French arranged to publish Chambers's encyclopedia in 1745. But, after a fight with the English translator, they decided to develop a greatly expanded French version instead. By 1747, Denis Diderot had assumed leadership of the project -- except for mathematical parts, which were handled by the mathematician d'Alembert.

Diderot added real fire to the project. He was briefly jailed in 1749 for his liberal views, and when the first two volumes were published in 1751, he was attacked by Jesuit authorities.

The problem was that Diderot and the other writers were rationalists. The work was now titled Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of Science, Arts, and the Trades, and it was on its way to becoming a 28-volume treatise on human affairs. The Dictionnaire, as it was called, laid bare the workings of the known world in a way no one had ever tried to do. It boldly told the average man that he could know what only kings, emperors, and their lieutenants were supposed to know. It suggested that anyone should have access to rational truth. In that sense it was a profoundly revolutionary document.

And the French government didn't miss the point. They twice tried to suppress the Dictionnaire. Yet the work was completed in 1771. That was little more than a decade ahead of the French Revolution, which it helped to foment.

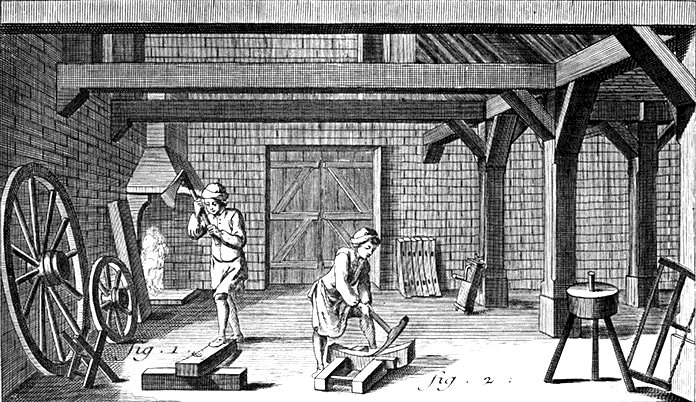

The Dictionnaire nurtured revolution both by including the trades along with the arts and sciences, and by recognizing the intimate link between technology and culture. But oh, how gracefully it did that job. Its beautiful plates show, in wonderful detail, how tanning, printing, metal-founding, and all the other production of the period was done.

But the Dictionnaire was published on the eve of the English industrial revolution as well as the French revolution. The trades Diderot described were just about to undergo a complete transformation. The technical descriptions ultimately served the history of technology better than it served technology itself. The irony is that it left us with a fine record of techniques that had been perfected, with little real alteration, since the Middle Ages.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

I am grateful to Pat Bozeman, Head of Special Collections, UH Library, for her counsel and for providing important background material available -- including the Dictionaire itself.

For another view of Diderot, see Episode 920. For more on encyclopedias, see Episode 203.

(Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library)

Wagon wheel making as depicted in Diderot's Dictionnaire.