Ahead of its Time

Today, a journal tries to read the tea leaves. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The new journal, Flying, first came out in January, 1901, three years before the Wright Brothers flew. The subtitle reads, The Journal of Aeronautics with which is incorporated the Flyer, the Flying Machine, the Aeronaut. In my new book, How Invention Begins, I diagnose the huge buildup that takes place as any new technology takes shape. Well, this journal gives a fine example of both the gathering Zeigeist at the turn of the last century, as well as the unpredictability (even in the near-term) of any technological future. The first picture in the Journal shows Samuel Pierpoint Langley.

Langley was the horse everyone knew would win the Triple Crown of heavier-than-air flight. His and Santos Dumont's names appear again and again. Eleven days before the Wrights flew, Langley's Aerodrome would make its last attempt at flight, and collapse into the Potomac next to the houseboat from which it was launched.

The same year the Wrights flew, we read about Santos Dumont's work on lighter-than-air-flight. He'd had recently won a prize by flying a seven-mile circuit around the Eiffel Tower in under thirty minutes. We also read about the earlier dirigible-maker Charles Renard who'd used battery powered electric motors in 1885.

But Santos Dumont uses internal combustion engines, which are starting to look a lot more safe and appealing, and he's hard at it with other projects. Santos Dumont eventually built eleven dirigibles, only to grow frustrated and switch to heavier-than-air machines. He made the first European airplane in 1906.

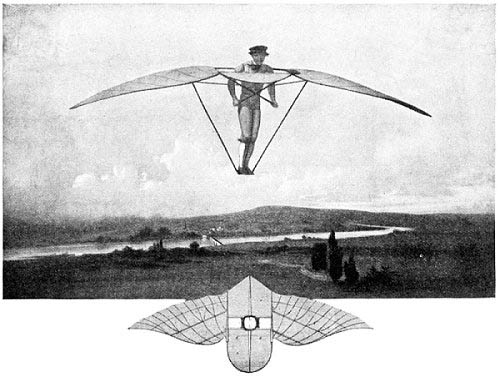

So the birds gather: Regular human flight is the dream of the ages and it'll soon take place. Yet its ultimate form hovers out of reach. This article about Santos Dumont, "The New Airships in Paris," has only one illustration and it's a surprise. It's one we find in many books and magazines of these times -- a much-copied picture titled, "Aerostat, Worked by Manual Power. Invented by W. Miller, M.R.C.S., 1843."

A man is supported between two crank-powered wings. This is an ornithopter so primitive it might've come from a Leonardo sketchbook. The man flaps his way over lovely open fields, calling us all to share in the dream of leisurely riding with the birds.

No one ever did manage to make a human-powered flapping-wing ornithopter. (Just stop to think what part of a bird provides the most meat. It is the breast -- the powerfully developed pectoral muscles which power the wings.)

So we turn pages and witness the express-train intensity that was about to yield powered flight. Yet two ideas lurk as we do: One is the longing expressed by Miller's dreamy but impossible Aerostat. The other is our own awareness of the Wright Brothers, working methodically off this particular radar screen -- soaking it all up and preparing to blind-side everyone within the year.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Flying: The Journal of Aeronautics. See especially, "New Airships in Paris, January 1903, pp. 211-213.

For more on this period, see J. H. Lienhard, How Invention Begins: Echoes of Old Voices in the Rise of New Machines. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.): See especially Chapters 3 and 8.

Aerostat, Worked by Manual Power. Invented by W. Miller, M.R.C.S., 1843. (But, of course, never built and flown.)

Replica of Santos Dumont's second airplane, the Demoiselle, made in 1907-9 -- called The Infuriated Grasshopper. (Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome, photo by JHL)